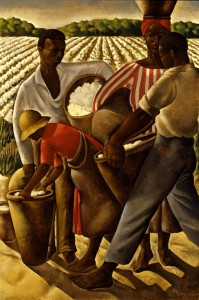

Just when it seemed that the country was recovering from the Depression, the 1940s plunged us into World War II. The depictions of the war here focus on the effects of the war on the families that were left behind on the homefront. The colorful depiction of a rural African American family bidding their loved one goodbye as he goes off to fight for his country is a reminder of the minorities who fought for our freedom and the struggles and discrimination they encountered trying to serve their country. Artist Thomas Hart Benton’s drawing of a woman reading a letter by lantern light reminds us of the harsh realities of war. The quiet solemnity of the scene combined with the swirling storm clouds leaves the viewer uneasy, anxious about the contents of the letter. Though the war ended with an Allied victory, more than 400,000 American soldiers would not come home. Additionally, this pair allows us to start a dialogue with students about what war was like on the homefront; topics include military recruitment and the draft, rationing, war bonds, and the mobilization of the American economy which virtually ended the unemployment of the previous era.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

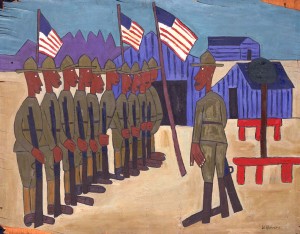

William H. Johnson began painting scenes of World War II in 1942. His paintings capture the experiences of black soldiers: leaving home, marching to camp, training for battle, and performing army chores. Johnson also painted a series of works illustrating the important contributions made by African Americans to the American Red Cross during the war.

A young woman sits reading a letter by the light of a lamp. Behind her, a farmed landscape stretches below a stormy sky. How are this woman and her letter typical of the American experience during the Second World War? What clues has Thomas Hart Benton given us to how she and the nation are feeling?

Observation: What do you see?

Off to War

A young man says goodbye to his family before boarding a bus leaving to go off to war. Clutching a duffel bag, he smiles brightly as he strides forward. His crisp uniform and black boots contrast with his father’s work pants, suspenders, and bare feet. The family is turned away from us, yet we see the father’s arm around his younger child. Johnson elongates the arms of the parents and the soldier, and exaggerates the size of their hands to emphasize their farewell wave. How does the young man feel about his departure? Does William H. Johnson feel the same way?

The family is wearing clothes of white and blue. The child holds an American flag. The many strong vertical lines of the house, the flag, the chimney, the crops in the field, and the family’s posture suggest an ordered rhythm. In contrast, the horizon is a pale yellow, with a blazing orange sun surrounded by purple clouds. The soldier is moving toward a future less certain and more perilous than the home he is leaving behind. The strong lines of the telephone poles serve as crucifixion symbols, suggesting the sacrifice that soldiers and families were making during the war.

Americans felt a surge of patriotism after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. The attack on American soil prompted America’s direct participation in the war and people felt compelled to lend their support. The flag gives the soldier’s departure a defined purpose. He is leaving to become part of the force defending the nation.

Letter from Overseas

A woman sits on a fence as she reads a letter by the warm glow of a lantern. A mailbox left ajar, and her straw hat flung carelessly at her feet, suggest the urgency with which the letter was received. During World War II, letter writing was the only way that American families could communicate with soldiers fighting overseas. The arrival of a letter was a highly anticipated event. It could take months for a letter from a loved-one to arrive, and when it did, it might be missing large portions that had been censored by the military. A mail truck in the distance delivers another note, perhaps to a neighboring family.

The sky above the woman, with its menacing swirl of clouds, suggests the turbulence of a nation at war. The moon emerges dramatically from the clouds to shed light on a lonely expanse of agricultural land. The young men who went to fight in World War II left a shortage of farm and factory labor. Perhaps the woman reading the letter was one of the many housewives who stepped up to take on the additional role of household provider in order to both fill this demand and provide for their family. The roles of women and traditional farming systems had to adapt to supply the nation with food.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Off to War and Letter from Overseas highlight the bond between soldiers and their families as well as the social changes that World War II prompted. The pain of danger and distance are present in each work, but they are outweighed by the love and the pride that their subjects feel.

Over a million African American men and women served in World War II, two decades before the 15th Amendment secured their right to vote. The discrimination faced by black soldiers during their service was a catalyst for the 1960s civil rights movement. Many of William H. Johnson’s paintings celebrate the contributions that African Americans made to the war effort. His work addresses segregation in the military at that time and makes the experience of these men and women real to the viewer. In Off to War, he has captured a complicated moment. While Off to War can be called a hopeful and patriotic painting, it is not without menace. The soldier and his family are proud that he is leaving to serve his country, but the forbidding background, with its yellow sky and dark crosses, point to danger in the soldier’s future.

A letter from overseas would have been a comfort in troubling times. News of the war with its victories and losses placed families in a state of anxiety. It was difficult or impossible for them to obtain specific information about the soldier they loved without a letter from him. As men left for Europe and the Pacific in huge numbers, life changed quickly for women. It became necessary for them to aid the war effort and take up the jobs left vacant by soldiers in addition to preforming the duties traditionally marked out for women.

Historical Background

African Americans in the Military

While the fight for African American civil rights has been traditionally linked to the 1960s, the discriminatory experiences faced by black soldiers during World War II are often viewed by historians as the civil rights precursor to the 1960s movement. During the war America’s dedication to its democratic ideals was tested, specifically in its treatment of its black soldiers. The hypocrisy of waging a war on fascism abroad, yet failing to provide equal rights back home was not lost. The onset of the war brought into sharp contrast the rights of white and black American citizens. Although free, African Americans had yet to achieve full equality. The discriminatory practices in the military regarding black involvement made this distinction abundantly clear. There were only four U.S. Army units under which African Americans could serve. Prior to 1940, thirty thousand blacks had tried to enlist in the Army, but were turned away. In the U.S. Navy, blacks were restricted to roles as messmen. They were excluded entirely from the Air Corps and the Marines. This level of inequality gave rise to black organizations and leaders who challenged the status quo, demanding greater involvement in the U.S. military and an end to the military’s segregated racial practices.

Onset of War:

Soldiers Training, ca. 1942, William H. Johnson, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 irrevocably altered the landscape of World War II for blacks and effectively marked the entry of American involvement in the conflict. Patriotism among both whites and blacks was at an all-time high. The country emphatically banded together to topple the Axis powers. Days after the attack, African American labor organizer A. Philip Randolph argued in an article entitled “The Negro Has a Great Stake in This War,” that despite the limitation of American democracy for African Americans, it was their obligation, responsibility and duty to serve because they were American citizens:

Japan has fired upon the United States, our country. We, all of us, black and white, Jew and Gentile, Protestant and Catholic, are at war, not only with Japan, but also with Hitler and the Axis powers. What shall the Negro do? There is only one answer. He must fight. He must give freely and fully of his blood, toil, tears and treasure to the cause of victory . . . We are citizens of the United States and we must proudly and bravely assume the obligations, responsibilities and duties of American citizens. . . . Moreover, the Negro has a great stake in this war. It is the stake of democracy – at home and abroad. Without democracy in America, limited thought it be, the Negro would not have even the right to fight for his rights.

Yet others disagreed. At the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) annual conference NAACP president Arthur Spingarn professed, “Democracy will not and cannot be safe in America as long as 10 per cent of its population is deprived of the rights, privileges, and immunities plainly granted to them by the Constitution of the United States. . . . We must unceasingly continue our struggle against the attempt to weaken the military strength of our country by eliminating from the military forces a tenth of our population.”

While not yet directly involved with World War II, the United States had issued the Selective Training and Service Act, which became law on September 16, 1940, creating the draft. It was thought prudent to start training soldiers in the event the United States joined the fray directly. The main provision of the act called for the drafting of 800,000 American men between the ages of 21 and 35. Two secondary provisions spoke to the discrimination question. Section 4 (a) stated that “In the selection and training of men under this Act, and in the interpretation and execution of the provisions of this Act, there shall be no discrimination against any person on account of race or color.” Unfortunately, Section 4 (a) essentially amounted to smoke and mirrors, as the act provided the addition that the armed forces would ultimately have final say over the eligibility of any potential draftee to serve, effectively giving them control over how many African Americans were admitted. Additionally, the act failed to address the issue of segregated military units. The War Department’s objections to military integration and the enlistment of African Americans were summarized by Secretary of War Harry Woodring, who stated that “The enlistment of Negroes . . . would demoralize and weaken the effectiveness of military units by mixing colored and white soldiers in closely related units, or even in the same units.”

Convalescents from Somewhere, ca. 1942, William H. Johnson, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The same month the draft was created several civil rights activists including Walter White of the NAACP, A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), and T. Arnold Hill of the National Urban League, met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to present their case for full African American integration into the American armed services. This included allowing black women to serve as nurses in the Army, Navy, and Red Cross; the appointment of black officers based on merit not race; and the opening of the Air Corps to African Americans. Roosevelt conferred with military officials and within weeks the War Department announced that blacks would be admitted to the armed services in the same proportions as white soldiers and that all branches of the military would be open to enlistment for blacks. However, black officers could only serve in black regiments and black members of the Air Corps would serve in a black-only unit; the announcement clearly stated that it was “not the policy to intermingle colored and white enlisted personnel in the same regimental organizations.” It was clear that despite these small victories, segregation would continue.

Philip Randolph became dismayed at the slow pace of progress and so in January 1941 he began organizing a march on Washington protesting not only the discriminatory racial practices of the military but also the exclusion of blacks from employment in the defense industries. With the full support of the NAACP, Randolph promised that 50,000 to 100,000 marchers would descend upon the capital. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a staunch supporter of integration and civil rights, met with Randolph in an attempt to have him call off the march. The march was suspended after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, also known as the Fair Employment Act, on June 25, 1941. The act banned discrimination in the government and defense industries stating that “it is the policy of the United States to encourage full participation in the national defense program by all citizens of the United States, regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin, in the firm belief that the democratic way of life within the Nation can be defended successfully only with the help and support of all groups within its borders.”

Lessons in a Soldier’s Life, ca. 1942, William H. Johnson, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Once the United States entered the war on December 8, 1941 following the attack on Pearl Harbor, many African Americans fervently advocated for more African American inclusion in the war, yet others could not ignore the hypocrisy of the situation with which they were faced. America had joined a war that opposed fascism and discrimination abroad, yet subjected a segment of its citizens to discriminatory practices and segregation. The irony of this was not lost, especially among young African Americans. Many wondered why they ought to serve. George Schuyler, a noted columnist for the popular black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, argued, “Why should Negroes fight for democracy abroad when they are refused democracy in every American activity except tax paying?” African American writer C. L. R. James retorted, “Why should I shed my blood for Roosevelt’s America . . . for the whole Jim Crow, Negro-hating South, for the low-paid, dirty jobs for which Negroes have to fight, for the few dollars of relief and insults, discrimination, police brutality, and perpetual poverty to which Negroes are condemned even in the more liberal North?” Others went as far as to compare the racism and discrimination faced by African Americans in the South to the racial policies and theories of Adolph Hitler.

Yet some African Americans were enthusiastic for black participation, seeing the war as a way to improve their position within American society. Army Sergeant James Tillman recalled that while he and other blacks faced many obstacles, they were fighting for something of far greater importance, the end of segregation:

It was rough all the way, but we were dedicated. We were fighting for a greater cause, for our people. I didn’t want to see what they were doing to the Jews happen to us, and the Germans wanted to do it to everybody. We had to defeat them, and we had to prove that blacks would fight. . . . We couldn’t quit. If we failed, the whole black race would fail. We were fighting for the flag and for our rights. We knew that this would be the beginning of breaking down segregation.

Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms

While given nearly a year before the United States entered World War II, the Four Freedoms Speech outlined four essential freedoms which everyone, everywhere should be entitled to enjoy. In the speech, part of the 1941 State of the Union Address, President Franklin D. Roosevelt imparted the four freedoms as such: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of every person to worship God in their own way, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Despite Roosevelt’s magnanimous belief and good intentions, his words rang hollow to the ears of the millions of African Americans who knew that all of these freedoms did not, and would not, apply to them, as they faced discrimination, rejection, and abuse on a daily basis. In The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, an African American soldier’s wife wrote to the editor the following letter:

Why must our husbands and brothers go abroad to fight for principles they only ‘hear’ about at home? Does our War Department believe in the Constitution of our country? Are the ‘Four Freedoms’ excluding our Southern States? Does the ‘Commander in Chief’ realize what’s going on in the hearts and minds of his colored soldiers? How long does he expect them to tolerate these deplorable conditions? Is he training them to be brave, courageous soldiers on foreign soil and mere mice here at home? Does it matter to him whether or not these men leave the shores of their homeland with the deep feeling of peace in knowing they must go to protect, and insure, Liberty and Justice to ALL here at home? Is the appeasement of the South worth the sacrifice of America’s most loyal citizens? How long will this farce of Democracy continue before our President and War Department begin practicing what they preach? I wonder.

Air Force Captain Luther H. Smith pointed out that while discriminated against, he and other black men volunteered to serve a country that discriminated against them because they believed it was their duty to protect their country: “We were black. We had lived a life of racial prejudice, discrimination, and bigotry. We were used to being considered second-class citizens, yet we have volunteered to join the military and fight in defense of the United States.”

Discrimination in the Military

Of all of the branches of the military there were only two that would admit black soldiers during World War II; the Army and the Navy. The Marines, the Air Corps and the Coast Guard were limited to white servicemen only. However, these units kept black servicemen who were primarily appointed as laborers, cooks, or messmen. African American Marine sergeant Thomas McPhatter recalled, “The only jobs we could have here in the Marines were either taking care of the dead or ammunition, which is what I did. I joined the Marines because I thought I could avoid bigotry and racism, but I ran smack into it. No matter what skills I had, all they would let me do was take care of the ammunition

Once at camp, African American soldiers were completely segregated from their white counterparts. Barracks for blacks were usually located away from the main portion of the camp in order to avoid confrontation between the races. Essentially the housing for black soldiers became its own segregated camp, often dubbed “the Negro Area.” At established camps, the older, more dilapidated housing was allotted to black soldiers, while whites were given preferential treatment and occupied newly constructed barracks. Sergeant Henry Jones, stationed at the Carlsbad Army Airfield in New Mexico, detailed his experiences in a Jim Crow camp in a letter to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. His letter of March 8, 1943 described a camp in which black soldiers were abused and denied equal access to camp facilities. For example, of the 1,000 seat theater available for the soldiers’ recreation, only twenty seats in the rear were made available to blacks. Additionally, blacks were denied access to the general store on base and frequently had to walk everywhere to and from the base because the southern bus system was not available to them. Jones wrote to the First Lady, “We do not ask for special privileges. . . . All we desire is to have equality; to be free to participate in all activities, means of transportation, privileges and amusements afforded any American soldier.”

Discrimination and prejudice not only occurred with the other servicemen, but with civilians as well, especially in the South. This became a prominent issue as more than eighty percent of African Americans were sent to the South for training. Many Southern communities expressed concern at having armed African Americans stationed close to them. Officers at the training camps routinely passed blacks over for promotions and assigned them menial and humiliating jobs. In the South it was expected that the black soldiers would adhere to the Jim Crow, even if they came from the North.

By January, 1943, only 375,000 African Americans had been admitted to the armed forces, out of a total 16 million Americans that would serve over the course of the war. As the number of African Americans in the military increased, the War Department tasked General Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the first African American general in the United States Army, to lead its inspector general’s office where he served on the Advisory Committee on Negro Troop Policies. Davis believed that the armed forces had the chance to set an example and improve race relations for the entire country, writing:

In the development of our national defense I believe the War Department has a wonderful opportunity to bring about better race relations. Policies of discrimination practiced with the current sanction of the federal government will not make the democracy we talk about in our attempt to rally the nation to our program of national defense. . . . Officers white and colored most certainly should have the same preparation. They must prepare together, live together, march together, share the hardships of the campaign. Then only will they be in a position to be mutually helpful in combat.

Discrimination on the Homefront

Before U.S. entry into World War II, 8 million Americans, 7 million white and 1 million black, remained unemployed. While the New Deal provided relief to many who suffered as a result of the Great Depression, it could not stave off all unemployment. The advent of the war necessitated a greater need for factory workers to build tanks and other military equipment. Yet, white workers were given priority over black workers for defense jobs.

Prior to 1941, defense industry jobs were not open to African Americans. Thanks to labor leader A. Philip Randolph’s tireless efforts in petitioning President Franklin D. Roosevelt to integrate the armed services, the president issued Executive Order 8802 on June 25, 1941. Also known as the Fair Employment Act, it covered not only those serving in the armed forces, but also those working in defense industries on the homefront. It also established the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), which ensured assistance to blacks and other minorities seeking jobs in the homefront industry during the war. Consequently those defense jobs which had been previously prohibited to African Americans began to open up. Also, the number of African Americans in the domestic service industry also declined and those in skilled jobs increased leading to a large occupational diversification amongst African Americans, the likes of which had never before been seen in the United States.

The Second Great Migration

The Second Great Migration (1940-1970) is considered by historians as the sequel to the Great Migration (1910-1930). While both had a tremendous impact on the lives of African Americans, the second migration was much larger in scale and dissimilar in character to the initial migration and arguably affected the lives of African Americans much more. The second migration precipitated a more enduring transformation of American life for both blacks and whites; many of the factors that spurred migration remained the same. The economy, jobs, and racial discrimination remained top factors for black migration to the North. The advent of World War II contributed to an exodus out of the South, with 1.5 million African Americans leaving during the 1940s, a pattern of migration which would continue at that pace for the next twenty years. The result would be the increased urbanization of the African American population, with fewer blacks working in agriculture or domestic labor, occupations in which the black race had previously been concentrated.

Employment of Negroes in Agriculture, 1934, Earle Richardson, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Economic Conditions

The New Deal’s efforts to rescue the Southern agricultural industry in the 1930s essentially backfired and forever transformed the region’s economy. Dire economic conditions in the South necessitated the move to the North for many black families. The expansion of industrial production during World War II and the further mechanization of the agricultural industry, in part, spurred the Second Great Migration.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (1938) had intended to help the South by paying farmers subsidies to not plant a portion of their land, thereby reducing the crop surplus and raising the value of the crop. While on the surface this was a sound plan, a major negative effect of the law was that it eliminated many jobs on which African Americans relied. The reduction in planted acreage meant that fewer workers were needed to harvest the crops. Also, the subsidies that the federal government gave the farmers induced them to reconsider mechanization, which up until that point had been very costly. But now with a guaranteed profit coming from government subsidies, farmers had little reason not to mechanize. This increased mechanization of the farming industry further reduced the need for agricultural workers. Additionally by 1940, the United States was no longer producing the majority of the world’s cotton, the primary money-making crop of the South. In fact, the South itself no longer remained the chief producer of cotton in the United States, with production shifting to California and Arizona.

Employment Opportunities

An opportunity for good, steady employment was one of the main reasons for African-Americans to pack up their belongings and move north. After all, jobs were vital in providing food, clothes, and shelter for families. The mobilization of the American wartime economy in 1942 produced more than $100 billion in government contracts in just six months, creating a plethora of new job opportunities in the North, the predominant area of manufacturing. Industrial hubs such as New York City, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Detroit were attractive due to the number of jobs available to blacks. During World War II over 1 million African Americans would join the workforce.

Industrial jobs were particularly appealing to younger African Americans because of the assistance they could receive through free government training programs sponsored by the National Youth Administration. The agency, part of the Works Progress Administration, aimed to train and educate American youth, ages 16-25. Unlike its counterpart, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the National Youth Administration was open to women looking for education and career opportunities. Of the 1 million African Americans who found work during the war in industrial occupations, 600,000 were women.

Racism and Violence

In addition to the terrible economic conditions, Southern blacks wished to move North because of the Jim Crow laws and continued racial violence in the South. A letter published in the Chicago Defender summed up the fear felt in that region: “Dear Sir, I indeed wish to come to the North – anywhere in Illinois will do so long as I’m away from the hangman’s noose and the torch man’s fire. Conditions here are horrible with us. I want to get my family out of this accursed Southland. Down here a Negro man’s not as good as a white man’s dog.”

While the North certainly had its share of racism, the South by comparison was unequivocally hostile to African Americans. Family and friends who had previously made the journey wrote to their loved ones in the South, writing about their wonderful new lives in the North and the opportunities that existed, “Hello Dr., my dear old friend. These moments I thought I would write you a few facts of the present conditions in the North. People are coming here every day and finding employment. Nothing here but money – and it’s not hard to get. I have children in school every day with the white children. However are times there now?”

The Homefront

Approximately 16 million Americans served in the various branches of the United States armed services during World War II. Each one of those 16 million people left loved ones behind on the homefront. From 1941 to 1945, American women faced a multitude of challenges they had never before faced. In addition to their time-honored roles as mother and nurturer, they now added father and provider to their growing list of responsibilities. Many joined the work force to aid in the depletion of factory workers the war had brought on. These jobs not only supplemented the meager government paychecks earned from a husband’s military service, but they also helped to alleviate the loneliness felt by the absence of a loved one. World War II marked the beginning of women getting out of the kitchen and into the workforce en masse for the first time in American history. Women on the homefront proved that they could successfully contribute to and participate within American society, disproving previous concepts of a woman’s abilities.

Women in American Industry

You knock ’em out–We’ll knock ’em down More Production, 1942, John Falter, lithograph, Smithsonian American Art Museum

With the depletion of the male American work force during World War II, the American industry turned to previously neglected groups to fill the void. African Americans and women jumped at the chance to prove that they could contribute not only to the war effort but to society as a whole. The need for workers during wartime was great. In 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that “in some communities employers dislike to hire women. In others they are reluctant to hire Negroes. We can no longer afford to indulge in such prejudice.” Between 1940 and 1945, six million joined the American work force. Many of these women went to work in these traditionally male-dominated industries, such as aircraft and ship building. Additionally, more than a quarter of a million women joined the various branches of the military, for the first time working in roles other than that of a nurse. The women who took on these jobs also had to juggle responsibilities back home. In addition to their eight to ten hour shifts, women were expected to cook, clean and complete all the domestic chores they had done before the war.

Additionally, the confluence of women from different races and backgrounds in the workplace provided an environment that bred civility. Factory worker Inez Sauer recalls how her preconceptions about African Americans were false:

I learned that just because you’re a woman and have never worked is no reason you can’t learn. The job really broadened me. I had led a very sheltered life. I had had no contact with Negroes except as maids or gardeners. . . . I found that some of the black people I got to know there were very superior, and certainly equal to me – equal to anyone I ever knew. I learned that color has nothing at all to do with ability.

War Communication

Communication between those serving in the military overseas and those left behind on the homefront was entirely reliant on letter writing. A lifeline between those separated by war, letter writing was a daily or weekly event in most households. Letters from servicemen helped to assuage the worries of those back home, while letters from the homefront reminded soldiers that they were not forgotten. Soldiers would write encouraging words, informing their loved ones that they were in good health, eating well, and safe from danger. Loved ones would often write of seemingly ordinary daily tasks and events that helped remind soldiers of the life they left behind.

In 1942 the government provided servicemen with free mailing privileges, which no doubt helped the volume of mail sent back home to increase in epic proportions. It also circulated lists of names and addresses of soldiers to the American public encouraging them, especially young women, to write letters to soldiers whom they did not even know in an effort to bolster troop morale. This special type of mail came to be known as V-Mail or Victory Mail. V-Mail was written on a single sheet of paper, with the contents written on one side. The sheet was then folded in half and addressed on the blank side. Thus, V-Mail was advantageous because it was lighter and used less paper than traditional letters which required envelopes. For this reason V-Mail became the most popular way to reach one’s loved one overseas. The mail was delivered twice a day in American towns and cities and became the highlight of one’s day.

The letters that those on the homefront received were often censured. It was not uncommon for large portions to be cut out of a letter. Other forms of communication like newspapers and radio also under operated under strict orders to censure any potentially injurious information that could fall into the hands of the enemy. A popular saying at the time was, “A slip of the lips sinks ships,” a reminder that one could inadvertently aid the enemy. To combat this, some families and servicemen devised their own coded words so that they could secretly pass on messages. As war wife Shirley Hackett explained:

You lived for the mail, yet the mail was censored, and it was not priority-shipped; it was always left for the very last thing. My husband wrote to me every day, but I sometimes didn’t hear from him for three months. When the mail did come, often it was censored so much that you couldn’t possibly figure out what he wanted to tell you in the letter. We knew very little about what was actually going on in the battlefield until much later. You worried because you didn’t know anything. We had radio, but the war news was censored and very little was in the newspapers that told you anything.

Though letter writing must seem tedious to today’s young generations, the letters were invaluable to the servicemen who received them. They provided support, strength and comfort in a war zone where there was none to be found. Soldier Elliot Johnson described what it was like for the servicemen to receive letter from loved ones:

While we were overseas, letters from our loved ones, including our girlfriends and wives, really sustained us. The mail came in very irregular batches, though. Sometimes for several weeks we wouldn’t get any letters at all, then we would get an enormous amount of mail. And sometimes the letters that had been mailed first arrived many weeks after those which had been mailed last. But letters were a big part of our emotional stability, because they made us feel like we were still a part of the people back home, that we hadn’t been forgotten.

Radio and newsreels were other means by which the American people kept informed about the war overseas. Newsreels played in movie theaters before the featured film. For some families who were lucky enough to catch their loved one on the newsreel, projectionists would replay the newsreels over and over for the families after the main feature.

While letters were welcomed, telegrams were not for they contained news of a tragic nature: the death of a serviceman, a missing-in-action notice, or news of a serious injury. Shirley Hackett recalled, “Everybody dreaded a telegram. You almost hated to answer the phone at times.” Over the course of World War II 300,000 American soldiers were killed and an additional 700,000 sustained injuries in varying degrees of severity. For those that did not return home, their families hung white silk pennants adorned with gold stars as a notice that their loved one would not be returning home.

Rationing and Life on the Homefront

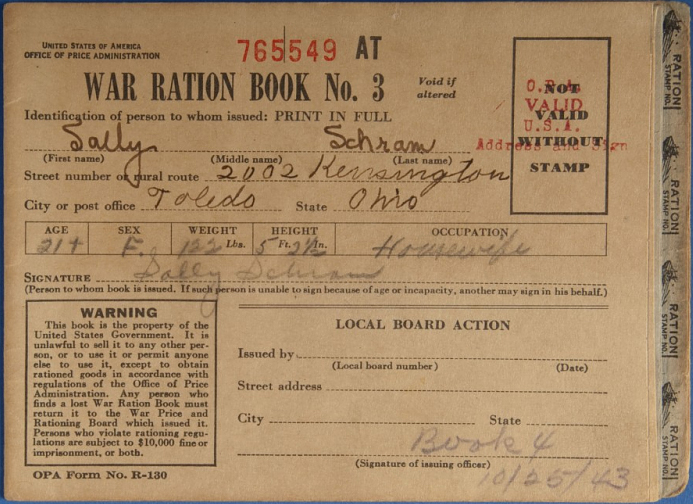

The onset of World War II had brought an end to the Great Depression due to the increase in commercial production. Industrial production was in full force as factories and farms raced to produce supplies for the war effort. While this occurred, rationing became a large part of everyday life for those on the homefront. Rationing food to the civilian population helped to make food and supplies available to the military. Civilian food shortages were common, as ships that would normally carry imported food were now diverted for military use.

Rubber became a scarce item as many rubber-producing areas in the Pacific had been invaded by the Japanese, effectively cutting off America’s supply of rubber, required it be added to the growing list of rationed items. Gasoline was added shortly afterward, as the government hoped that by rationing fuel, people would be less likely to drive and unnecessarily wear down their vehicle’s rubber tires. Stickers were placed on cars indicating the driver’s gasoline consumption allowance. Those who relied on cars to get to work or provide emergency services were provided with more rations, while those who only drove for pleasure were rationed the least amount of gasoline. Mechanics were kept busy repairing cars as no new ones were being manufactured; all metal was being diverted for the building and maintenance of tanks and military equipment.

The first of the wartime rationing began in May of 1942 with sugar. Ration books were soon added for coffee, red meat and canned foods. Milk, eggs and butter, while not rationed, became scarce in some areas. One wife wrote her husband in 1943 about the shortages and rationing:

Last week we didn’t have a scratch of butter in the house from Monday until Friday – and how I hate dry bread! It’s a lot worse on we people in the country than it is on the city folks. They can go out and get some kind of meat every day while we have plenty of meatless days here. They can also stand in line for 2 or 3 hours for a pound of butter, but up here there are no lines as there is no butter and when there is a little butter everyone gets a ¼ of a pound. So you can imagine how far a ¼ of a pound goes in this family of five adults. And that’s supposed to last us for a week.

The government encouraged citizens to plant their own fruit and vegetable gardens to compensate for the produce that American farmers were sending to the military. These gardens quickly became known as Victory Gardens.

Women’s magazines took on new roles, providing wartime advice and tips on keeping a family healthy, preparing meals with rationed food, solo parenting and shopping frugally. Food companies like General Mills created the persona of Betty Crocker and published a cookbook entitled Your Share: How to Prepare Appetizing, Healthful Meals with Foods Available Today. The cookbook advised women that they “must make a little do where there was an abundance before. In spite of sectional problems and shortages, you must prepare satisfying meals out of your share of what there is. You must heed the government request to increase the use of available foods, and save those that are scarce – and, at the same time, safeguard your family’s nutrition.” The image that was perpetuated of the female American homemaker was one who was self-reliant, efficient and the emotional support center of the home. Women were advised to cope with the pressures of wartime living “nobly and unselfishly.” Ladies’ Home Journal was considered one of the most trusted outlets for advice and the most read, boasting a circulation of more than four million.

Primary Source Connections

War Ration book, 1942

War Ration book, 1942

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

World War II had a profound impact on the American home front. Populations shifted as workers migrated toward military-industrial centers, and wartime labor shortages meant more women and minorities were able to enter the workforce. The federal government took on new roles, such as requiring that civilians ration gasoline, food, textiles, and other goods in short supply during the war.

“The Negro Has a Great Stake in This War” – by A. Philip Randolph, December 20, 1941, Pittsburgh Courier

“The Negro Has a Great Stake in This War” – by A. Philip Randolph, December 20, 1941, Pittsburgh Courier

The attack on Pearl Harbor irrevocably altered the landscape of World War II for blacks. Patriotism among both whites and blacks was at an all-time high. The country emphatically banded together to topple the Axis powers. Days after the attack, African American labor organizer A. Philip Randolph argued that despite the limitation of American democracy for African Americans, it was their obligation, responsibility, and duty to serve because they were American citizens

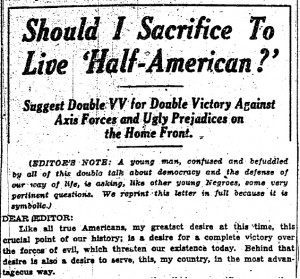

“Should I Sacrifice to be Half American FULL?'” – Letter to the Editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, January 31, 1942

James G. Thompson, a young black man, writes to the editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, “confused and befuddled by all this double talk of democracy and the defense of our way of life.” He asks questions many African Americans wondered at the time, such as “Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for the sacrificing of my life?” Many blacks wondered by they should go to war to protect others’ civil rights, when their rights were not being honored by their own country.

Artwork Connections

Soldiers Training , ca. 1942, William H. Johnson

, ca. 1942, William H. Johnson

Pearl Harbor inspired two government-sponsored art exhibitions in 1942, for which William H. Johnson painted scenes of African Americans involved in the war effort. Soldiers Training contrasts the patriotism of black enlistees with the military’s segregationist policies. Black soldiers served in their own units, “black” blood was kept separate from “white,” and recruits took on the most menial jobs at Army bases and aboard ships.

Johnson may have painted this scene based on reports of the “Buffalo Soldiers” who were training at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. Set in a desolate camp ringed by mountains, Soldiers Training suggests the isolation that black soldiers experienced among hundreds of thousands of men and women committed to winning the war.

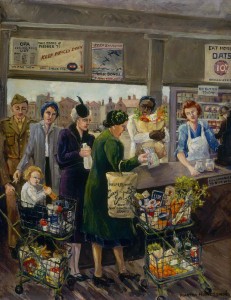

Wartime Marketing , 1942, Martha Moffett Bache

, 1942, Martha Moffett Bache

This artwork provides a glimpse of life on America’s home-front during World War II, when food was scarce and conserving became an important patriotic duty. In a grocery store, people stand in line to buy their food. The artist chose a title for the painting that may have a dual meaning: Wartime Marketing. The people she painted are in the process of “marketing,” or buying goods, in the grocey store, but they are also surrounded by the heavy advertising (or “marketing”) that was part of life during the War.

At the top left of the painting, an OPA ceiling price list is visible with a message urging customers to help keep prices down. The OPA, or the Office of Price Administration, set limits on how much could be charged for everyday items in order to hold back inflation. Next to this is a poster with the prominent words “Keep ‘Em Flying” written across the top in red. This popular slogan was widely used to promote patriotic actions such as conservation, rationing, and the purchase of war bonds. The man in uniform serves as a reminder of the soldiers fighting abroad and the overall goals of these home-front efforts.

Media

World War II Part 1: Crash Course US History – PBS (13 min) TV-G

This video teaches you how the United States got into the war, and just how involved America was before Congress actually declared war. The video discusses the military tactics and weaponry involved, specifically the huge amount of aerial bombing that characterized the war, and the atomic bombs that ended the war in the Pacific.

World War II Part 2 – The Homefront: Crash Course US History – PBS (14 min) TV-G

In this video, you’ll learn about how the war changed the country as a whole, and changed how Americans thought about their country. The video talks about the government control of war production, and how the war probably helped to end the Great Depression.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

The Art and Life of William H. Johnson – Smithsonian Education

Students examine works by African American painter William H. Johnson to learn about his milieu as well as his style. This set of lessons is divided into grades K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12. Younger students list the elements of the pictures, identifying colors and shapes and such objects as farm equipment, crops, and animals. Older students compare Johnson’s work with that of painter Allan Rohan Crite.

Subject: History

The Price of Freedom: World War II – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Americans joined the Allies to defeat Axis militarism and nationalist expansion. After Japanese air forces attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States entered a global war that had been raging for nearly two years. Sixteen million Americans donned uniforms. The millions more who stayed home comprised a vast civilian army, mobilized by the government to support the war effort. This online exhibition provides historical essays paired with primary resources.

WWII on the Homefront: Civic Responsibility (PDF) – Smithsonian Education

Rationing During the War Era – Smithsonian Education

A 1942 genre painting, Wartime Marketing, opens this study of American life during World War II. By rolling their cursor over the painting, students find background information on some of its details, along with additional primary-source images. They learn about wartime shortages and conservation and the “home front ammunition” of foodstuffs. In a lesson plan, they go deeper into a study of the painting itself. Included is a short Office of War Information film.

Victory Mail Online Exhibit – Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Victory Mail, more commonly known as V-Mail, used standardized stationery and microfilm processing to produce lighter, smaller cargo. Space was made available for other war supplies and more letters could reach military personnel faster around the globe. This new mode of messaging launched on June 15, 1942. In 41 months of operation, letter writers using the system helped provide a significant lifeline between the frontlines and home. This website features in-depth information on V-Mail, classroom materials, and related resources.

Glossary

Agricultural Adjustment Act: (1938) a New Deal era law which reduced agricultural production by paying farmers subsidies to not plant part of their land in order to reduce crop surplus, therefore effectively raise the value of crops.

Benjamin O. Davis Sr.: (1877-1970) the first African-American general in the United States Army. During WWII, he lobbied for the full integration of U.S. troops.

Betty Crocker: a persona for the General Mills Company. During the war, several Betty Crocker cookbooks were published instructing American women how to care and provide for their families when products were rationed.

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters: founded in 1929, it was the first labor organization led by African-Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor.

Civilian Conservation Corps: a New Deal era public relief program for males ages 18-23. The Corps provided unskilled manual labor jobs relating to the conservation and development of natural resources. This provided aid to families recovering from the Depression and at the same time implemented a natural resources conservation program in each state.

Chicago Defender: founded in 1905, a historically black newspaper for African-American readers. The paper played a major role in the Great Migration, promoting Northern cities as preferable destinations.

Executive Order 8802: also known as the Fair Employment Act, signed on June 25, 1941 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the act prohibited discrimination against blacks in the defense industry.

Great Migration: (1910-1930) the first wave of African American migration to the North from the South.

Jim Crow: state enforced segregation and disenfranchisement laws against African-Americans; enacted after the Reconstruction era.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): African-American civil rights organization, founded in 1909 to “ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to eliminate racial hatred and racial discrimination.”

National Youth Administration: a New Deal agency that provided employment and education for citizens ages 16-25; part of the Works Progress Administration.

Ration books: a collection of ration “coupons,” which allowed the owner of the coupons a certain amount of product each month. Food, leather, rubber, clothing, and gasoline were some of the items rationed and especially needed for the war effort.

Selective Training and Service Act: (1940) the first peace-time United States draft which required all males between the ages of 21 and 35 to register. When the U.S. entered WWII, the age range for conscription was changed to 18-65.

V-Mail: the primary mode of getting message to soldiers stationed abroad during WWII. Messages were censored, copied to film, and printed back onto paper for the intended recipient when it reached its destination. This system was much more cost effective for the military.

Victory Gardens: also known as war gardens, the government encouraged the planting of fruits, vegetables, and herbs were planted in private residences and in public parks to aid the war effort. By growing their own foods, American citizens aided the war effort by alleviating the labor shortage needed to harvest and transport these products. The gardens were also considered a morale booster for those on the homefront.

Works Progress Administration: the largest New Deal agency that employed millions of people to carry out public works projects. These projects included roads, public buildings, bridges, dams and more.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 8 – The Great Depression and World War II

- Standard 3B – The student understands World War II and how the Allies prevailed.

- 7-12 – Describe military experiences and explain how they fostered American identity and interactions among people of diverse backgrounds.

- Standard 3C – The student understands the effects of World War II at home.

- 5-12 – Explain how the United States mobilized its economic and military resources during World War II.

- 7-12 – Evaluate how minorities organized to gain access to wartime jobs and how they confronted discrimination.

- 7-12 – Analyze the effects of World War II on gender roles and the American family.