Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way

(mural study, U.S. Capitol), 1861, Emmanuel Gottlieb Leutze

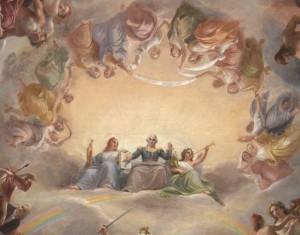

Study for the Apotheosis of Washington in the Rotunda of the

United States Capitol Building, ca. 1859-62, Constantino Brumidi

The philosophy describing the necessary expansion of the nation westward was called Manifest Destiny; the belief that it was our duty to settle the continent, conquer and prosper. The idealized depiction of settlers who have reached the promised land of the west is depicted in Emanuel Leutze’s mural study Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way. The settlers have overcome hazardous terrain and death in order to reach the American West, bathed in a welcoming golden light.This vision of the frontier as a promised land persisted. There was a price to be paid, however. Frontiersmen had to be willing to face the risks inherent in migration – but had their parents not faced similar risks in coming to America? They had to be willing to do the backbreaking work required to turn a wilderness into prosperous farms and towns – but had their ancestors not done that as well? They had to be willing to break with the familiar and comfortable, and face hardship – perhaps even death. The finished mural, located in the United States Capitol Building, served as propaganda for many Americans looking for a brighter future. This was something that was sorely sought after the time – for at the time this work was painted, the Civil War had just begun.

The theme of American destiny continues in another Capitol mural study, this one for the dome on the Capitol Building. Artist Constantino Brumidi has focused on the eminence of America. At the center is its founding father, George Washington, surrounded by allegories of American inventions and leaders which helped put this country on the path to greatness. This mural was also painted during the Civil War and was intended to serve as a symbol of the Union’s steadfastness and as a celebration of the nation’s greatness. The completed Capitol dome mural was finished in one month, April 1865, the same month in which the Confederacy surrendered and Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

Download a Teaching Poster PDF of Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way

(mural study, U.S. Capitol)

Emanuel Leutze painted Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (mural study, U.S. Capitol) during of one of the most tumultuous times in American history – the onset of the Civil War. The painting celebrates the belief that the American West held both unspoiled beauty and infinite promise for a better future. It advocates Manifest Destiny, the belief that it was America’s divinely ordained mission to settle and civilize the West – an alliance between nation-building and religion. What can we learn about the ideals surrounding westward expansion from this artwork? How do artists employ symbolism to augment a specific message in their work? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting and then placing them in historical context enables the viewer to interpret the artist’s overall message

Observation: What do you see?

In his 1862 notes, Emmanuel Leutze described the central image as a scene of immigrants, having labored to the top of the hill, observing the flat, golden West spreading before them with the rocky, cold “valley of darkness” at their backs. The surging crowd of figures records the births, deaths, and battles fought as European Americans settled the continent to the edge of the Pacific. Central among them is a three-person family group seated on a promontory and looking to the sunset – an allusion to the Biblical holy family. Leading the migrants – some of whom are walking injured, others driving exhausted mules before covered wagons – are a band of frontiersmen clearing a path toward their “promised land.”

At the bottom of the composition are small, round portraits of explorer William Clark, at left, and frontiersman Daniel Boone, at right. The portraits flank a landscape painting of San Francisco Bay – the western destination of the pioneers. Both men were entrusted to lead settlers into western territories, with Boone exploring and settling the lands of Kentucky, and Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) a pioneer explorer of the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase and later governor of the Missouri Territory.

Focus now on the margin. What symbols or stories do you recognize?

Leutze wrote of the border: “All subjects in the margins are but faintly indicated without any attempt at imitation or deception and kept entirely subservient to the effect of the Principal picture.” The artwork on the borders reinforces the composition’s overall message with a blend of mythological and Biblical allusions. These fall into two broad themes: predetermined fate and the hero’s journey. In one section, Leutze depicts the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts. We see Jason’s ship, the Argo, sailing home with the Golden Fleece shown on its sail. This fleece, having been won after a long quest, fulfills a prophecy and returns Jason to his rightful place as king. At the top left are the three Magi – travelers from the east – who figure into the Nativity in the Bible’s New Testament. They gaze up at the star that will, ultimately, lead them to Jesus’ birthplace so that they might present him with gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Leutze wrote of the border: “All subjects in the margins are but faintly indicated without any attempt at imitation or deception and kept entirely subservient to the effect of the Principal picture.” The artwork on the borders reinforces the composition’s overall message with a blend of mythological and Biblical allusions. These fall into two broad themes: predetermined fate and the hero’s journey. In one section, Leutze depicts the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts. We see Jason’s ship, the Argo, sailing home with the Golden Fleece shown on its sail. This fleece, having been won after a long quest, fulfills a prophecy and returns Jason to his rightful place as king. At the top left are the three Magi – travelers from the east – who figure into the Nativity in the Bible’s New Testament. They gaze up at the star that will, ultimately, lead them to Jesus’ birthplace so that they might present him with gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Leutze reinforces his theme of exploration through a profile portrait of Christopher Columbus (left), seemingly taking measure of the world with a globe and calipers. At the bottom right, Leutze situates a dove bearing an olive branch. Here he alludes to the end of the Old Testament flood. The dove carries proof of dry land to Noah, bearing with it assurances that his seven-month journey across a decimated, watery world is nearing its end.

Leutze reinforces his theme of exploration through a profile portrait of Christopher Columbus (left), seemingly taking measure of the world with a globe and calipers. At the bottom right, Leutze situates a dove bearing an olive branch. Here he alludes to the end of the Old Testament flood. The dove carries proof of dry land to Noah, bearing with it assurances that his seven-month journey across a decimated, watery world is nearing its end.

At the top of the margin, front and center, is an American eagle with wings spread. Green banners curl outward, heralding the painting’s title: “Westward the course of empire takes its way.” This line begins the closing stanza of a poem by British philosopher Bishop George Berkeley. In it, Berkeley predicted that Western expansion would make America the site of the next golden age. At the far left and right of this detail, Leutze explained, are “Indians creeping and flying before them [the eagle’s banners]—to the left the axeman, preceded by the hunter whose dog has attacked a catamount [cougar], the Indian creeping, discharging an arrow at the hunter.”

Interpretation: What does it mean?

What significance might this image have held for Americans at the start of the Civil War?

Emmanuel Leutze was trained abroad as a history painter. Curator Richard Murray explained: “History painting is not necessarily the facts as they occurred, but how an artist could arrange the facts to make a significant point.”

In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase almost doubled the size of the United States. Over the next few decades the status of newly admitted western states and territories as free or slave would add fuel to the already contentious relationship between the North and the South. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed the people living in those territories to decide whether slavery was allowed within their borders. This “popular sovereignty” caused pro- and anti-slavery settlers to flood the land with the goal of voting slavery up or down. This ultimately led to violent political confrontations known as “Bleeding Kansas” – the most significant event to presage the Civil War. By the time Leutze executed this mural study in 1861, the war was underway and the nation torn in two.

With Westward the Course… Leutze encoded a message of national unity, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This study, and the final mural that would ultimately decorate the House of Representatives side of the U.S. Capitol, embodies ideas of “Manifest Destiny,” elevating the journey to settle the western United States to mythical status. To that end, Leutze wove together images of the past and present, suffering and success, juxtaposing the hardships of the pioneer voyagers with the triumphs of heroes and explorers. He chose the vignettes of heroes on the move for the margin to reinforce this point. Leutze intended to provide “glorious examples of our great men for the benefit of future generations, and as a token of a nation’s glory, that they may be continued as our history advances.”

Study for the Apotheosis of Washington in the Rotunda of the

United States Capitol Building

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What can we learn about the way our country saw itself and wished to present itself around 1860? What clues does the artist, Constantino Brumidi, give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Look at this overall image. What do you notice about shape of this picture? How about your viewpoint? Where do you think you would find it hanging in a museum?

This painting is round and, apart from the group of figures in the center, can be seen correctly from anywhere around its circular edge. Does it feel like you are looking up when you view the painting? This work hangs flat on a gallery wall in the museum, but it is a study – or a draft – created by the artist. The final work is much, much larger in size and is painted on a ceiling. This work is the study for the mural that the same artist painted in the Rotunda, the space inside the dome of the Capitol of the United States.

Who is in the center of the composition?

The nation’s first president George Washington is seated at the center of the composition, flanked by allegorical figures representing liberty and victorious fame. At Washington’s right side, the allegorical figure of Liberty sits wearing a blue toga and red cap, holding a fasces. The cap, called a Phrygian cap, was worn by freed slaves in ancient Rome and is a symbol of freedom. The fasces, a bundle of sticks from which the blade of an axe protrudes, was an emblem of power for Roman magistrates. To Washington’s left is Victory or Fame. With one hand, she holds a horn to her lips, as though to announce victory, and with the other she carries a palm branch, a symbol of both peace and triumph.

The nation’s first president George Washington is seated at the center of the composition, flanked by allegorical figures representing liberty and victorious fame. At Washington’s right side, the allegorical figure of Liberty sits wearing a blue toga and red cap, holding a fasces. The cap, called a Phrygian cap, was worn by freed slaves in ancient Rome and is a symbol of freedom. The fasces, a bundle of sticks from which the blade of an axe protrudes, was an emblem of power for Roman magistrates. To Washington’s left is Victory or Fame. With one hand, she holds a horn to her lips, as though to announce victory, and with the other she carries a palm branch, a symbol of both peace and triumph.

How many figures hover over the central group of figures? Why is this significant?

Thirteen women form an arc over the central group. These allegorical figures represent the thirteen original colonies of the United States. Together, they hold a banner which reads, E Pluribus Unum, “out of many, one,” the motto of the United States.

Who is fighting below Washington? Who is winning and how can you tell?

Directly below George Washington is a woman brandishing a sword and a shield emblazoned with stars and stripes. This is Freedom. She is accompanied by an eagle, the symbolic bird of the United States, and stands above a group of vanquished enemies. Though for the most part the figures are allegorical, the artist has slyly inserted representations of real-life rebels, like that of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy during the Civil War. This nod to contemporary life was made more apparent in the final mural which graces the ceiling of the Capitol Building dome.

Directly below George Washington is a woman brandishing a sword and a shield emblazoned with stars and stripes. This is Freedom. She is accompanied by an eagle, the symbolic bird of the United States, and stands above a group of vanquished enemies. Though for the most part the figures are allegorical, the artist has slyly inserted representations of real-life rebels, like that of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy during the Civil War. This nod to contemporary life was made more apparent in the final mural which graces the ceiling of the Capitol Building dome.

Can you locate Benjamin Franklin among the groups? Who is standing next to him?

Can you locate Benjamin Franklin among the groups? Who is standing next to him?

The Roman goddess of Wisdom, Minerva, stands next to Franklin, guiding him and other learned men of significant importance in America’s history. Included are Robert Fulton, developer of the first successful steamboat and Samuel F.B. Morse, developer of the first successful electromagnetic telegraph and of Morse code. Minerva presides over these inventors, her arm outstretched appearing to impart her gift of knowledge.

Let’s take a look at the remainder of the figure groups. What symbolic significance to American history or culture do they hold?

Moving in a clockwise motion, we see Neptune, Roman god of the sea, and behind him an ironclad warship – an innovation which revolutionized the American navy. The goddess Venus emerges from the sea holding the first transatlantic cable, which was being laid at the time this work was painted. Stretching nearly 2,000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean, the cable enabled telegraph communication between the U.S and Britain.

Continuing around the circular composition, in the next figure group Mercury, the Roman god of commerce, holding the caduceus – his traditional symbol of a winged staff intertwined with two snake. In his other hand he extends a bag of money to Robert Morris, the financier of the Revolutionary War and the founder of the Bank of the United States.

Continuing around the circular composition, in the next figure group Mercury, the Roman god of commerce, holding the caduceus – his traditional symbol of a winged staff intertwined with two snake. In his other hand he extends a bag of money to Robert Morris, the financier of the Revolutionary War and the founder of the Bank of the United States.

The next figure group features Vulcan, Roman god of the forge, who was the creator of the weapons and armor of the gods. Here we see parts of a cannon at his feet and a massive steam pipe looming behind him. Both the cannon and steam engine are devices associated with American progress and military might.

The Roman goddess Ceres appears at the center of the last figure group. Ceres, the goddess of the harvest, is identified by her cornucopia, the horn of plenty. She is seated on the McCormick Reaper a machine that was patented in 1834 and replaced the handheld scythe. It revolutionized the harvesting process by mechanizing the cutting, threshing, and harvesting of grain. Holding the reins of Ceres’ horses is America herself, also depicted wearing a Phrygian cap of freedom. Flora, the goddess of flowering plants and springtime, gathers flowers nearby.

The Roman goddess Ceres appears at the center of the last figure group. Ceres, the goddess of the harvest, is identified by her cornucopia, the horn of plenty. She is seated on the McCormick Reaper a machine that was patented in 1834 and replaced the handheld scythe. It revolutionized the harvesting process by mechanizing the cutting, threshing, and harvesting of grain. Holding the reins of Ceres’ horses is America herself, also depicted wearing a Phrygian cap of freedom. Flora, the goddess of flowering plants and springtime, gathers flowers nearby.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

An apotheosis is the process of elevating someone to divine status, or showing how they are god-like. In raising George Washington, America’s first and arguably greatest hero, to this status Brumidi has effectively cemented Washington’s legacy as a great leader. The “mythical” George Washington surrounded by allegorical figures from Roman mythology presents America as the new Roman Republic – both powerful and free, destined for greatness. The scenes of gods, goddesses, and notable Americans that surround Washington highlight America’s achievements in science, commerce, agriculture, and military technology. The design conveys both America’s triumphs and its confidence in a bright future. George Washington literally rises above all of America’s progress in the center of the domed painting. When you consider that this study, and the final dome painting, were created during the height of the Civil War, another layer of context is added. This image presents a hopeful scene to the nation that although we are divided now, we were once great and can be great once again.

Historical Background

Manifest Destiny and U.S. Westward Expansion

The phrase “Manifest Destiny” originated in the nineteenth century, yet the concept behind the phrase originated in the seventeenth century with the first European immigrants in America, English Protestants or Puritans. Manifest Destiny is defined as “the concept of American exceptionalism, that is, the belief that America occupies a special place among the countries of the world.” The Puritans came to America in 1630 believing that their survival in the new world would be a sign of God’s approval. As their ship the Arbella neared shore, group leader John Winthrop gave a sermon entitled “A Modell [sic] of Christian Charity,” in order to prepare his fellow passengers for what lay ahead. His sermon stressed the importance of this experimental religious settlement in the new world, and how it would come to serve as an example for all settlements thereafter, stating “For wee [sic] must consider that wee [sic] shall be as a citty [sic] upon a hill. The eies [sic] of all people are upon us.” Winthrop also recalled God’s instruction in the Bible about the need to expand and prosper, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.” The ideology of Manifest Destiny continued through the eighteenth-century as victorious America won independence from Great Britain, an event that many occasioned to be preordained and lauded by God and an example of American exceptionalism.

The use of the term “Manifest Destiny” did not enter conventional conversation until 1845, when journalist John Louis O’Sullivan wrote that it was “our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.” Nineteenth-century expansionism went hand in hand with the concept of Manifest Destiny, each signaling that there was a God-given, sanctioned right to conquer the land and displace the “uncivilized,” non-Christian peoples who, it was believed, did not take full advantage of the land which had been given to them. This ideology served as justification for the violent displacement of native peoples and the forceful takeovers of land by military means. Nineteenth-century Americans expanded upon Winthrop’s notion of “a city upon a hill” to encompass the idea that all countries should look to the United States as a model nation. Just as sixteenth-century Puritans had seen it as their divine right to “tame and cultivate” the frontier, so too did nineteenth-century capitalists and politicians see the expansion of the frontier as providential, their personal and professional profit in harmony with the nation’s economic development.

U.S. Territorial Expansion

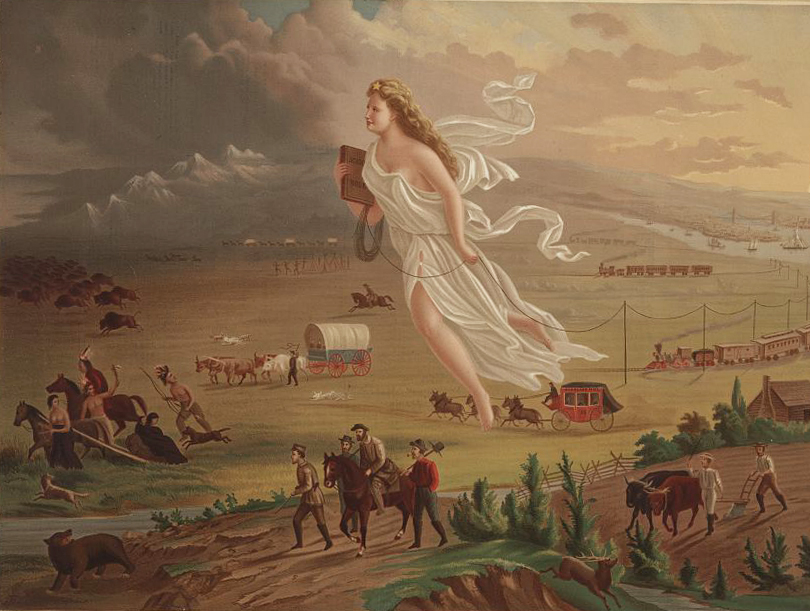

American Progress, 1872, John Gast, Library of Congress

The European settlers who came to America in search of a new life believed that land acquisition was crucial to their future prosperity. Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France and the subsequent exploration of that western territory by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the nation’s appetite for expansion grew. The Louisiana Purchase, which tripled the size of the young country, effectively started a chain reaction for U.S. territorial expansion. The next fifty years of American history saw the nation increase its land holdings exponentially: in 1845 Texas was incorporated into the U.S.; Britain’s 1846 treaty with the U.S. gained the young nation the disputed Oregon territory; California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada and Utah were incorporated following the 1848 war with Mexico; and finally, in 1853, the Gadsden Purchase completed the last contiguous land purchase in the continental U.S., finalizing the southern borders of New Mexico and Arizona as we know them today. In 1846 Walt Whitman wryly opined on the relentless territorial expansion, stating “The more we reflect upon annexation as involving a part of Mexico, the more do doubts and obstacles resolve themselves away. . . . Then there is California, on the way to which lovely tract lies Santa Fe; how long a time will elapse before they shine as two new stars in our mighty firmament?”

Expansion and the Artwork

Emmanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s mural study for the Capitol in Washington, D.C. celebrates the idea of Manifest Destiny just when the Civil War threatened the republic. The surging crowd of figures in the painting records the births, deaths, and battles fought as European Americans settled the continent to the edge of the Pacific. Like Moses and the Israelites who appear in the ornate borders of the canvas, these pioneers stand at the threshold of the Promised Land, ready to fulfill what many nineteenth-century Americans believed was God’s plan for the nation.

Leutze’s painting depicts westward expansion as a difficult task leading to a heavenly reward represented by the fertile golden valley below. Yet actual pioneers made the overland trek, either by wagon or train, only to discover that the so-called Promised Land at the end of their journey was a lonely, inhospitable place. In Six Years on the Border, or, Sketches of Frontier Life (1883) Mrs. J.B. Rideout describes how her family had left New England for the West because they “had heard of a village on the banks of a beautiful river, surrounded by a rich country fast filling up with intelligent people . . .” After the hazardous trip overland, the Rideouts arrived at their destination:

We reached the town of which we had read such glowing accounts before leaving the East . . . and as I stood in the village which had appeared to my imagination in so many different forms, feeling homesick and discouraged, I looked around and counted the buildings. One blacksmith’s shop, one small store, one dwelling-house and two little cabins . . .”

Traveling an average of fifteen miles a day, the pioneers usually took between five and six months to reach Oregon or California. During the journey they faced skirmishes with Native Americans and diseases such as cholera and typhoid fever. Often trapped in the mountains by winter snows (instead of gloriously reaching their summits, as Leutze’s imagination shows), the pioneers often had to slaughter their mules and oxen for food and proceed on foot. Leutze’s painting includes a burial, a man with a bandaged head, and other references to the hardships the pioneers actually faced. Yet his image remains a glorifying account of westward migration.

In order to achieve the realism of the Pacific Coast Mountains, Leutze made the decision to make the arduous journey out west in order to sketch the views from life. Having received an advance on his salary, the artist traveled out to the Rocky Mountains in August 1861, specifically to Pike’s Peak in Colorado, to study the topography of the western mountains. Leutze stated that it was his intent “to represent as near and truthfully as the artist was able, the grand peaceful conquest of the great west . . . Without a wish to date or localize, or to represent a particular event it is intended to give in a condensed form a picture of western emigration, the conquest of the Pacific slope.” His preparatory drawings were full of such rich detail, that little to no changes had to be made in the mural study concerning the topography and natural elements. Writing to the engineer of the Capitol, Montgomery C. Meigs, Leutze stated that he believed he had seen more of the West in his trip to Colorado than he would have had he gone as far as California.

The Capitol Dome Commission

The design process for the composition of the dome painting went through several stages before Brumidi developed the final study, which resides in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The artist made two prior studies before coming to the third and final composition. With this last concept, Brumidi was finally able to realize the mural’s circular composition and convey it on a smaller study canvas. In the third and final study, Washington is placed just below the center. The allegorical group of the original thirteen states provides a counterbalance on the opposite side of the dome, so at dead center is a golden-bathed sky. The figural groups that form the edge of the canvas are more fully developed in this third and final study, with all continuing to highlight American achievements in innovation, technology and agriculture, among others.

Brumidi would have been acquainted with the concept of an apotheosis from his time studying classical art in Europe. Additionally the concept of George Washington’s apotheosis was not new, for it had been illustrated in prints and engravings by many artists decades before Brumidi started to paint the Capitol dome. Yet the dome painting presented significant differences and challenges for Brumidi not encountered by any previous artists; namely, the scale of the artwork and the difficulty of executing a painting on a concave surface that made sense to the viewer no matter where they stood on the floor below the dome.

On September 8, 1862 Brumidi submitted his design to Thomas U. Walter, Architect of the Capitol, “for the fresco picture to be painted on the Canopy of the New Dome of the United States Capitol. . . . As this picture will be seen at a height of 180 ft. the painting must be of the most decided character possible. It will cover 4664 sq. ft. and will be worth $50,000 to execute including the necessary cartoons and every expense pertaining to the painting.”

Brumidi’s final design was approved by Walter, yet the approval came with one condition: Brumidi would have to execute the painting for a significantly lower price. Walter attempted to convince Brumidi that although his initial price had not been accepted, there were other merits to completing the job for a lower price:

I am aware, as you have expressed to me in conversation that there is no picture in the world that will compare with this in magnitude and in difficulty of execution. Being painted on a concave surface, and I am also aware that it covers about eight times more surface that Mr. Leutze’s picture which cost $20,000. . . . Should you execute this work it will be the great work of your life: it will therefore be worth on your part some sacrifice to accomplish so great an achievement.

By the end of December, Brumidi agreed to the lower asking price of $40,000 in order to expedite a settlement and begin work on the fresco as soon as possible. On March 11, 1863, Thomas U. Walter wrote to Brumidi to inform him that he could start work on the dome painting immediately.

We know that Brumidi’s work on the dome was underway shortly after November 1863, for in the Capitol’s Annual Report dated the first of that month, it is stated that the cartoons for the fresco are being prepared and “its execution will be commenced as soon as the iron work . . . can be put in place.” However, a series of bureaucratic delays and the delay of the completion of the iron framework for the dome delayed Brumidi’s start of the fresco until 1865. When he did finally start the fresco, the speed at which he covered the 4,664 square feet of the dome was remarkable; the fresco painting was completed in just eleven months.

At the center of the dome fresco painting, Brumidi has depicted America’s first president George Washington in full military regalia. The lavender cloth draped across his lap is evocative of the classical drapery found in the classical sculpture of Ancient Greece; the democratic society on which the American government was modeled. In a letter to Thomas U. Walter, Brumidi discussed the other main design elements in his final design: “The six groups around the border represent as you will see, War, Science, Marine, Commerce, Manufactures, and Agriculture. The leading figures will mesure [sic] some 16 feet. In the centre [sic] is an Apotheosis of Washington, surrounded by allegorical figures, and the 13 original Sister States.” The act of apotheosizing Washington effectively raised the nation’s first president to the rank of a god and glorified him as the ideal American – a standard to which it was believed that all Americans should strive to achieve. The apotheosis cemented George Washington’s image as national icon.

For further information on the symbolism and representations of American values and progress that Constantino Brumidi weaved throughout the fresco painting, visit the Architect of the Capitol’s interactive website at https://www.aoc.gov/capitol-hill/other-paintings-and-murals/apotheosis-washington

George Washington's Legacy in the 19th Century

The vast mural that covers the interior of the U.S. Capitol dome celebrates America, from her historical figures to her historic accomplishments. Central to all of these compositional elements is our nation’s founding father, George Washington. Seated amongst the heavens, Washington sits enthroned in the clouds. He is surrounded by allegories of the thirteen original colonies, further solidifying his contribution to the founding of the nation. This mural was painted sixty-six years after Washington’s death. Why was Washington chosen to be at the center of the composition? How did Washington’s legacy resonate with contemporary viewers in the 1860s approximately seventy-seven years after the end of the Revolutionary War?

In Washington’s lifetime his moral disposition and character were celebrated by his countrymen who defined his greatness by his inner virtue, a trait exhibited by his lack of interest in political ambition or personal gain. One powerful action that made Washington such an admired figure was that, although he was handed absolute power, he relinquished it once his duty as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army had been fulfilled. The resignation of his military commission, his relinquishment of power, conformed to the revered model of Cincinnatus, the ancient Roman farmer who when called to action by his country, set aside his farmer’s plow to take up arms in a time of great necessity, only to renounce absolute military power once the region entered a time of stability. John Adams once declared, “I glory in the character of Washington because I know him to be an exemplification of the American character.”

Upon Washington’s death, a Congressional committee was formed to prepare funeral and memorial arrangements for the much-beloved president. The original plan the committee formed was to intern Washington’s remains in a marble tomb beneath the dome of the United States Capitol Building, in a crypt below. Martha Washington consented to the plan for her husband’s remains, but she died before the tomb could be completed. Plans changed and Washington’s final resting place was relocated to Mount Vernon where, according to his will, Washington wanted to be buried all along. To this day Washington’s unused tomb remains in the Capitol.

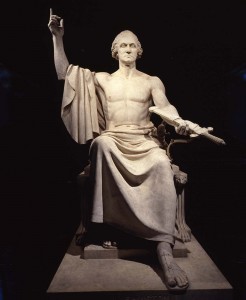

George Washington, 1840, Horatio Greenough, marble, Smithsonian American Art Museum

That the plan to bury Washington beneath the Capitol dome fell through did not deter the Capitol’s designers from wanting to commemorate the first president in that location. The first such commemoration was a monumental sculpture by renowned American sculptor Horatio Greenough for the center of the rotunda. The larger-than-life sculpture depicted a seated Washington clad in a toga, in a pose reminiscent of the Greek god Zeus. Unfortunately, Greenough’s half-naked George Washington created quite a scandal it’s time; an era characterized by decorum and modesty. The sculpture was promptly moved outside to the Capitol gardens. Brumidi adapted this pose for his fully-clothed version of Washington in the dome fresco painting.

After his death Washington remained, as elocuted by Continental Army cavalry officer Henry Lee, “first in the hearts of his countrymen.” Celebrations to commemorate his birth were planned. As the years passed after his death, he came closer and closer to deification. Washington’s name became synonymous with America, liberty, freedom and moral character. His popularity knew no bounds. Washington’s image graced everything from plates and teacups to fireplace mantles. One European traveler was amazed to find that “[E]very American considers it his sacred duty to have a likeness of Washington in his home, just as we have the images of God’s saints.” Furthering the notion that the apotheosis is the deification of Washington is a statement written by Gustave de Beaumont, traveling companion of Alexis de Tocqueville. While visiting America in 1831, Beaumont reflected: “I know that [America] has its heroes; but nowhere have I seen their statues. To Washington alone there are busts, inscriptions, columns; this is because Washington, in America, is not a man but a God.” Brumidi’s fresco which is arguably the grandest memorial dedicated to Washington, elevates the founding father to god-like status and in doing so venerates him as the ideal American.

For audiences in the mid-nineteenth century and during the time of the Civil War, George Washington became a unifying figure, one whom both the North and the South could look to as a role model. The North viewed the first president as a symbol for unity, while the South revered him as a stalwart opponent to tyranny. In fact, Washington was so revered by both sides that his home, Mount Vernon, was deemed neutral territory by both the Union and the Confederacy during the war.

Washington’s commemoration on the dome of the Capitol building exemplifies the idea that this memorial, and others like it, had more to do with the time period in which it was created rather than the past events the memorial actually depicted. Historian Michael Kammen has remarked that, “Societies in fact reconstruct their pasts rather than faithfully record them, and they do so with the needs of contemporary culture clearly in mind – manipulating the past in order to mold the present.” While not manipulating history, Brumidi presents us with a composition that speaks volumes to the power of the American spirit, depicting the triumph of our nation’s ingenuity. Brumidi would complete the fresco painting on the dome in a single month, April 1865, which saw two significant events in American history; the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox and President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. In the aftermath of the war, images of Washington helped soothe the nation’s wounds, reminding Americans that their nation was once great and could be great again.

Primary Source Connections

“Consideracons for the Plantacon of New England.” 1622, John Winthrop

View the document at the Library of Congress or Read a transcription (page 309)

“This pamphlet is a previously unknown, contemporary copy of John Winthrop’s “General Observations for the Plantation of New England,” written in the summer of 1629 to justify the Puritan migration to New England. Winthrop (1588-1649) offered a series of reasons for the proposed emigration and refuted various objections to the enterprise.” – Library of Congress

One of the first published references to “Manifest Destiny” by John Louis O’Sullivan, Eastern State Journal, January 29, 1846

One of the first published references to “Manifest Destiny” by John Louis O’Sullivan, Eastern State Journal, January 29, 1846

Download a High-Resolution PDF (The reference is located at the top of the sixth column, “The Oregon Question.”)

John Louis O’Sullivan, an American columnist and editor, is credited with coining the phrase “Manifest Destiny.” The concept had existed for a long time, but the phrase did not come into use until O’Sullivan used it in two editorials he wrote in July and December 1845—promoting the annexation of the Texas and Oregon territories, respectively—the phrase caught on immediately.

The Louisiana Purchase, April 30, 1803

Download images and learn more at OurDocuments.gov

“In this transaction with France, signed on April 30, 1803, the United States purchased 828,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for $15 million. For roughly 4 cents an acre, the United States doubled its size, expanding the nation westward.”

President Thomas Jefferson’s Message to Congress communicating the Discoveries of explorers Lewis and Clark

Read it at the National Archives

Following the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark were charged by President Thomas Jefferson in 1804 to explore the newly acquired territory west of the Mississippi River. For the next two years the expedition explored and mapped the western territory, studying plant and animal life, and establishing trade with Indian tribes.

A Year of American Travel, 1878, Jessie Benton Frémont

Read it at Archive.org (Excerpt from page 71)

Daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton and wife of explorer John C. Frémont, Jessie wrote this memoir documenting her and her husband’s explorations in the American West. The following passage details hardships endured during the journey westward.

Excerpt: Letter from Colonel Frémont to his wife, January 27, 1849 – “About the 11th of December we found ourselves at the north of the Del Norte Cañon, where that river issues from the St. John’s Mountain, one of the highest, most rugged, and impracticable of all the Rocky Mountain ranges, inaccessible to trappers and hunters even in the summertime. Across the point of this elevated range our guide conducted us, and having still great confidence in his knowledge, we pressed onward with fatal resolution. Even along the river-bottoms the snow was already belly-deep for the mules, frequently snowing in the valley and almost constantly in the mountains. The cold was extraordinary; at the warmest hours of the day (between one and two) the thermometer (Fahrenheit) standing in the shade of only a tree trunk at zero; the day sunshiny, with a moderate breeze. We pressed up towards the summit, the snow deepening, and in four or five days reached the naked ridges which lie above the timbered country, and which form the dividing grounds between the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Along these naked ridges it storms nearly all winter, and the winds sweep across them with remorseless fury. On our first attempt to cross we encountered a poudrerie, and were driven back, having some ten or twelve men variously frozen — face, hands, or feet. The guide became nigh being frozen to death here, and dead mules were already lying about the fires. Meantime it snowed steadily. The next day we made mauls, and, beating a road or trench through the snow, crossed the crest in defiance of the poudrerie, and encamped immediately below in the edge of the timber. The trail showed as if a defeated party had passed by — pack-saddles and packs, scattered articles of clothing, and dead mules strewed along. A continuance of stormy weather paralyzed all movement.”

Literary Connections

Fiction:

My Antonia, 1918, Willa Cather

My Antonia, 1918, Willa Cather

Read it at the Willa Cather Archive

The novel is an elegy about pioneer life in the American West. It fictionalizes events and recollections from the author’s life growing up in rural Nebraska.

New Found Land: A Novel, 2004, Allan Wolf – Grades 5 and Up

New Found Land: A Novel, 2004, Allan Wolf – Grades 5 and Up

Find it in a Library

Two hundred years ago, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark launched their wooden boats up the Missouri River in search of the illusory Northwest Passage, a journey that would capture the American imagination and help forge a young nation’s identity. Now, in a riveting debut novel, Allan Wolf tells the story of this extraordinary voyage through the eyes of not only the famed pair but also several members of their self-named Corps of Discovery.

Non-Fiction:

Across the Plains: With Other Memories and Essays, 1892, Robert Louis Stevenson

Across the Plains: With Other Memories and Essays, 1892, Robert Louis Stevenson

Read it at Archive.org

Plains is Stevenson’s memoir as an immigrant traveling from New York City to San Francisco on the transcontinental railroad.

Excerpt: “When I think how the railroad has been pushed through this unwatered wilderness and haunt of savage tribes and now will bear an emigrant for some twelve pounds from the Atlantic to the Golden Gates; how at each stage of the construction roaring, impromptu cities, full of gold and lust and death, sprang up and then died away again . . . and then when I go on to remember that all this epical turmoil was conducted by gentlemen in frock coats with a view to nothing more than a fortune and a subsequent trip to Paris, it seems to me, I own, as if this railway were the one typical achievement of the age in which we live, as if brought together into one plot all the ends of the world and all the degrees of social rank, and offered to some great writer the busiest, the most extended, and the most varied subject for an enduring literary work.”

Artwork Connections

Among the Sierra Nevada, California, 1868, Albert Bierstadt

Among the Sierra Nevada, California, 1868, Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt’s beautifully crafted paintings played to a market eager, in the 1860s, for spectacular views of the nation’s frontiers. Works such as this fueled the image of America as a promised land just when Europeans were immigrating to this country in great numbers. When the painting was shown in Boston, one critic recognized that the landscape was a fiction invented from Bierstadt’s sketches of the West. Nevertheless, the writer felt that it represented “what our scenery ought to be, if it is not so in reality.”

George Washington, 1840, Horatio Greenough

The first commemoration of George Washington in the United States Capitol Building was a monumental sculpture by renowned American sculptor Horatio Greenough for the center of the rotunda. The larger-than-life sculpture depicted a seated Washington clad in a toga, in a pose reminiscent of the Greek god Zeus. Unfortunately, Greenough’s half-naked George Washington created quite a scandal it’s time; an era characterized by decorum and modesty. The sculpture was promptly moved outside to the Capitol gardens.

Visit of the Prince of Wales, President Buchanan, and Dignitaries to the Tomb of Washington at Mount Vernon, October 1860, 1861, Thomas P. Rossiter

Visit of the Prince of Wales, President Buchanan, and Dignitaries to the Tomb of Washington at Mount Vernon, October 1860, 1861, Thomas P. Rossiter

The prince’s visit to the Revolutionary War leader’s grave in 1860 was celebrated as a sign of reconciliation between England and its former colonies.

Media

Constantino Brumidi’s “Study for the Apotheosis of Washington” (6 min)

Learn about the study for the “Apotheosis of Washington in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol Building,” about 1859-62, by Constantino Brumidi, with curator Eleanor Jones Harvey and chief conservator Tiarna Doherty.

Curator talk on “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way” (4 min)

Richard Murray, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, shows how to “read” a history painting as he takes a look at an epic work by German painter Emanuel Leutze.

How did Manifest Destiny Shape the American West? (2 min)

Maria Montoya on Manifest Destiny. From The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

“Approaching Research: Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

Smarthistory’s “Envisioning Manifest Destiny during the Civil War”

Subject: History

The Price of Freedom: Mexican War – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

America went to war to gain territory from Mexico and expand the nation’s boundary from Texas to California. President James. K. Polk believed it was the nation’s destiny to occupy these lands, and he planned an elaborate military campaign to seize them. This online exhibition provides historical essays paired with primary resources.

Envisioning Manifest Destiny (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

What did Manifest Destiny mean to the United States? How did Native Americans and African-Americans fit into Westward Expansion?

Lewis and Clark: Mapping the West – Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

This website sets the history stage for Lewis and Clark’s journey West, features online access to Lewis and Clark’s maps, and other primary resources, and provides related activities and lesson plans.

Lewis and Clark: The National Bicentennial Exhibition – Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Contains primary sources, interviews, maps, an image gallery, a virtual exhibition, and curriculum connections.

Glossary

Alexis de Tocqueville: (1805-1859) French historian and political thinker, best known for his book, Democracy in America, a study of American society.

allegorical: the expression of symbols through figures or events that stand for ideas about human life or for a historical or political situation.

American exceptionalism: the theory that the U.S. is inherently different from other countries.

apotheosis: the elevation or exaltation of a person to divine status.

Bleeding Kansas: a series of violent political confrontations resulting from the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, in which pro- and anti-slavery advocates all converged in in Kansas to vote by popular sovereignty (a vote by settlers, rather than outsiders) as to whether Kansas would be a slave state or a free state.

cartoons: full-sized preparatory drawings, designs, or paintings for a fresco from which the final work is traced or copied.

Cincinnatus: (519-430 B.C.) Ancient Roman statesman and aristocrat, regarded for his virtue and best known for his post-war resignation of complete power and authority.

deification: the act of elevating or glorifying to divine or god-like status.

expansionism: the belief that a country should grow larger; a policy of increasing a country’s size by expanding its territory.

fresco: a painting that is done on wet plaster. This technique was popular to paint large murals. From the Italian word fresco, meaning fresh.

Gadsden Purchase: the U.S. acquisition of a region in present-day Arizona and New Mexico via a treaty signed on December 30, 1853 between the United States and Mexico. The purchase’s purpose was so that the U.S. could build a southern route for the Transcontinental Railroad. This was the last territorial acquisition in the contiguous United States. The purchase is also known as the Sale of Mesilla.

Henry Lee: (1756-1818) cavalry officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolution; father of Confederate Civil War general Robert E. Lee.

Horatio Greenough: (1805-1852) American sculptor who worked almost exclusively for the United States government. He is best known for his controversial sculpture of a toga-clad George Washington, based on a statue of the Greek god Zeus by ancient Greek sculptor Phidias.

John Louis O’Sullivan: (1813-1895) American editor who coined the phrase “Manifest Destiny” in 1845 to promote the annexation of Texas and the acquisition of the Oregon territory.

John Winthrop: (1587-1649) English Puritan lawyer who led the first wave of Puritan immigrants to America in 1630.

Kansas-Nebraska Act: (1854) this bill was originally designed to enable settlers to move west to the land we know today as Kansas and Nebraska, and for the building of a Midwestern transcontinental railroad. Yet, the bill also allowed “popular sovereignty,” that is, it allowed the people living in those territories to decide whether slavery was allowed within their borders. Soon pro- and anti-slavery advocates flooded the land with the goal of voting slavery up or down, ultimately leading to violent political confrontations known collectively as “Bleeding Kansas” – the most significant event to presage the Civil War.

Louisiana Purchase: (1803) purchased from France during President Thomas Jefferson’s administration, the region of the United States encompassing land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains.

Manifest Destiny: the nineteenth-century doctrine or belief that the expansion of the U.S. throughout the American continents was both justified and inevitable.

Meriwether Lewis: (1774-1809) American explorer, soldier, and politician. He is most well-known for his role in the Lewis and Clark Expedition, exploring the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase.

Montgomery C. Meigs: (1816-1892) U.S. Army officer, civil engineer, and Quartermaster General during the Civil War. Meigs had a role in building many landmarks including the U.S. Capitol Building and Arlington National Cemetery.

Puritans: members of a sect of English Reformed Protestantism which emerged from the Church of England in the 16th century. Puritans, believing the church only partially reformed, sought to rid the church from all Roman Catholic practices. They practiced and advocated for greater strictness in religious discipline and for the simplification of doctrine and worship. Large-scale Puritan migration from England to America occurred from 1620 to 1640.

Robert E. Lee: (1807-1870) Confederate Civil War general.

Thomas U. Walter: (1804-1887) The fourth Architect of the Capitol, who was responsible for and oversaw the design and construction of the Senate and House wings and the dome of the U.S. Capitol Building.

Walt Whitman: (1819-1892) American poet and journalist.

William Clark: (1770-1838) American explorer and soldier. He best known as one-half of the exploring team of Lewis and Clark. Following the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark were charged by President Thomas Jefferson in 1804 to explore the newly acquired territory west of the Mississippi River. For the next two years the expedition explored and mapped the western territory, studying plant and animal life, and establishing trade with Indian tribes.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 4 – Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

- Standard 1A – The student understands the international background and the consequences of the Louisiana Purchase, the War of 1812, and the Monroe Doctrine

- 9-12 – Analyze how the Louisiana Purchase influenced politics, economic development, and the concept of Manifest Destiny.

- Standard 1C – The student understands the ideology of Manifest Destiny, the nation’s expansion to the Northwest, and the Mexican-American War.

- 5-12 – Explain the economic, political, racial, and religious roots of Manifest Destiny and analyze how the concept influenced the westward expansion of the nation.

- 5-12 – Explain the causes of the Texas War for Independence and the Mexican-American War and evaluate the provisions and consequences of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.