The question of whether or not to declare independence and throw off the chains which bound them to England was a question that weighed heavily on the minds of colonists in the years leading up to the American Revolution. Much was at stake including personal safety and economic security. Many colonists relied on business with Britain like Loyalist Robert Hooper, who was in the importing and exporting industry. Yet there were others, like Mrs. James Smith, who had everything to gain in the hopes that independence would secure a free future for her grandson Campbell. The book she holds in her lap is a book of oratory study, open to Shakespeare’s famous sonnet from Hamlet, “To be or not to Be,” thereby alluding to the uncertain future of the young nation and the young child.

Download a Teaching Poster PDF of Mrs. James Smith and Grandson

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Mrs. James Smith and Grandson

What can we learn about America in 1776 through Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of two family members representing different generations? What clues can we uncover about the sitters by analyzing the artist’s choices? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Compare and contrast the way Peale has painted and framed the faces of Mrs. James Smith and her grandson. What is similar, and what is different?

While there is a clear resemblance between grandmother and grandson (note the similarities in their head shapes and facial features), Peale has clearly differentiated their relative ages. Wrinkles and lines are visible on Mrs. James Smith’s face, contrasting with her grandson’s smooth, youthful skin. Whereas Mrs. James Smith is set against a dark background, there is a light source shining down on her grandson, illuminating him in a golden glow.

Compare the clothing of Mrs. James Smith and her grandson. What might the attire tell us about each figure, their social class, and their backgrounds?

Although members of the same family, there are some key differences in the way Mrs. James Smith and her grandson, Campbell Smith, are clothed. The outermost layer of Mrs. Smith’s attire is dark and somber in color, almost appearing to fade into the black background. The rest of her garments are all muted, neutral hues, lending her a respectable but subdued presence. Campbell’s blue jacket with gold buttons and embroidered vest display clearer signs of wealth, and the vibrancy of the brighter colors emphasize his youth in contrast with his grandmother’s age. The vines embroidered on Campbell’s vest may symbolize growth and potential.

Although members of the same family, there are some key differences in the way Mrs. James Smith and her grandson, Campbell Smith, are clothed. The outermost layer of Mrs. Smith’s attire is dark and somber in color, almost appearing to fade into the black background. The rest of her garments are all muted, neutral hues, lending her a respectable but subdued presence. Campbell’s blue jacket with gold buttons and embroidered vest display clearer signs of wealth, and the vibrancy of the brighter colors emphasize his youth in contrast with his grandmother’s age. The vines embroidered on Campbell’s vest may symbolize growth and potential.

Research into the Smith family tells us that Mary and James Smith were Scoth-Irish immigrants to Pennsylvania, arriving in America sometime around the 1720s, and that they were farmers. Through profitable trade and Campbell’s father William’s political success, the family’s wealth grew significantly over the next two generations. This increased prosperity between Mary and Campbell Smith’s generations is reflected in the relative richness of their clothing.

Charles Willson Peale chose to depict Campbell Smith holding an open book, pointing to a specific page. What is he reading, and what might be its significance?

Books are a symbol of learning, and by placing one so prominently in Campbell Smith’s hands, Peale is putting the young boy’s education front and center for the viewer. In colonial America, early childhood education was primarily a family responsibility, often the purview of women in the household. By zooming in on the detail of the book, we can see that it is titled The Art of Speaking, and it is open to a page headed “Hamlet’s Soliloquy.” Campbell’s pointed finger seems meant to draw our attention to the famous opening line of the soliloquy, which begins “To be, or not to be – that is the question.”

Books are a symbol of learning, and by placing one so prominently in Campbell Smith’s hands, Peale is putting the young boy’s education front and center for the viewer. In colonial America, early childhood education was primarily a family responsibility, often the purview of women in the household. By zooming in on the detail of the book, we can see that it is titled The Art of Speaking, and it is open to a page headed “Hamlet’s Soliloquy.” Campbell’s pointed finger seems meant to draw our attention to the famous opening line of the soliloquy, which begins “To be, or not to be – that is the question.”

Oratory, the art of formal public speaking, was a highly prized skill in colonial America, particularly for men hoping to go into politics or law. By depicting Campbell Smith reading a book on oratory, Peale indicates the aspirations the boy’s family may have had for his prosperous and successful future. Indeed, Campbell’s father, William Smith, was a Continental Congressman from Maryland and would have known first-hand the importance of the ability to speak persuasively.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Charles Willson Peale contrasted two distinct generations within the same family in this portrait. Using visual techniques like the use of light and dark to heighten the contrast between the aging grandmother and the youthful grandson, Peale’s depiction of his sitters seems to allude to the major changes America was on the cusp of at the onset of the Revolution. In this portrait, the colonial past is represented by the grandmother gradually fades into the background, while passing on knowledge to her grandson’s generation, embodying the nation’s high hopes for a brighter future. Their clothing heightens this contrast, with the grandmother’s muted, traditional dress alluding to her modest upbringing and European ties, and her grandson’s richer, more colorful clothing indicating increased wealth.

Peale’s choice to have the book open to Hamlet’s Soliloquy can be interpreted in multiple ways. Perhaps Peale was alluding to the prosperous future Campbell Smith’s education was meant to prepare him for, and whether or not it would come to be. Knowing that the painting was made in Philadelphia in 1776, there is an additional layer of possible meaning here – for a new nation just declaring its independence from Great Britain and heading into a turbulent revolution, the future of the country was uncertain. Was the dream of independence to be, or not to be?

Robert Hooper

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What information can we learn about Robert Hooper and the Loyalist perspective in the American colonies from this painting? What clues does the artist give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

How has the artist represented Robert Hooper through his posture and facial expression?

John Singleton Copley has painted Hooper comfortably reclining in a chair and resting his arm casually on the window ledge behind him. He has the rotund physique of someone who probably does not have to do much manual labor for a living, and he looks calm and content as he gazes ahead.

What do Hooper’s clothing and surroundings suggest about his social class and economic status?

Hooper is well dressed, though not flashily. He wears his wedding ring prominently, evidence of his 1769 marriage to Anna Cowell. Marriage was an important way for upper-class families in the colonies to consolidate power and prosperity. He holds reading material in his other hand, demonstrating that he is educated. He sits upon a finely appointed chair, and behind him is a voluminous red curtain. His apparent comfort among these surroundings indicates that he belongs to an upper-class, wealthy elite.

Copley has given us a peek at the landscape outside the window. What is its significance?

We can see the ocean outside the open window behind Robert Hooper. Hooper’s father, Robert ‘King’ Hooper, made his sizable fortune through ownership of the largest and most profitable shipping business in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Copley has alluded to the source of the younger Hooper’s wealth by including the sea so prominently in his portrait.

The merchant class to which Hooper and his father belonged depended on trade with Britain to maintain their wealth. The Hoopers were politically-involved Loyalists, who found themselves at odds with their Patriot neighbors when they vocally supported the performance of then-Governor Thomas Hutchinson, a major proponent of British taxes on the colonies.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Copley has painted Robert Hooper as a man enjoying the comfortable life he has inherited through his father’s business. The trappings of his wealth and status surround him. The view of the sea through the open window references the shipping business that made the family fortune, and reminds us of Hooper’s Loyalist ties to Britain across the Atlantic.

Historical Background

Loyalists and Patriots

The Revolutionary War era was a time of immense turmoil for the American colonists, no matter where their allegiances lay. By comparing and contrasting these two artworks, we can examine both sides of the dispute over independence and how the issue directly affected the lives of those involved. Those who rebelled against the control and oppression of Britain were termed Patriots. The family of Mrs. James Smith and her grandson Campbell Smith were steadfast patriots, with many family members participating in the military and early government in order to secure independence from Britain. British Loyalists, like Robert Hooper, remained loyal to the English king during the war and made up approximately 15 to 20 percent of the population of the thirteen American colonies.

The Revolutionary War era was a time of immense turmoil for the American colonists, no matter where their allegiances lay. By comparing and contrasting these two artworks, we can examine both sides of the dispute over independence and how the issue directly affected the lives of those involved. Those who rebelled against the control and oppression of Britain were termed Patriots. The family of Mrs. James Smith and her grandson Campbell Smith were steadfast patriots, with many family members participating in the military and early government in order to secure independence from Britain. British Loyalists, like Robert Hooper, remained loyal to the English king during the war and made up approximately 15 to 20 percent of the population of the thirteen American colonies.

Political affiliations at this time were often dictated by economic factors and not personal concerns. Joining the rallying cry of “independence” was not a simple decision. Wealthy merchants in port cities were especially adverse to independence as it would harm their business. Those in the importing and exporting business, like Robert Hooper, relied heavily on trade with England. Their business was vital for providing for their families and so no matter their personal feelings, biting the hand that fed them was not an option.

Perhaps not by coincidence, the painters that were commissioned to paint these portraits shared the political sympathies of their sitters; Charles Willson Peale was an ardent Patriot and a member of the Sons of Liberty, while John Singleton Copley, a family friend of Robert Hooper’s, was a vocal Loyalist who was forced to flee to England to escape persecution for his political beliefs.

Loyalists

Loyalists were those in the colonies who remained loyal to the British crown during the American war for independence. They were also known as King’s Men, Tories, and Royalists. They considered themselves to be British citizens and therefore believed revolution to be treason. The majority of these Loyalists belonged to the wealthy merchant class in the colonies, their livelihood dependent on trade and good relations with Britain. Because of their strong affinity with Great Britain, it is not surprising that these colonists favored styles that were characteristically British, including the style of their portrait paintings.

British fashions and furnishings, designs and décor all were in vogue for the colonial elite to emulate. Wealthy colonial men and women, particularly Loyalists, were enamored with the current trends in British portrait painting. While these men and women could afford to travel to sit for famed British artists like Thomas Gainsborough or Joshua Reynolds, many chose to employ an artist in the colonies who had similar training and stylistic attributes as Gainsborough and Reynolds. For the elite in Boston, only one artist had all of these qualities – John Singleton Copley. Not only was Copley trained in London, but his own personal political leanings were that of a Loyalist.

The Hooper family of Marblehead, Massachusetts, a port town just north of Boston, were one of Copley’s richest patrons and provided Copley with numerous commissions. From 1763 until Copley left American shores in 1774, he painted many members of Robert Hooper Jr.’s family including his father, step-mother, and several of his siblings. In the colonies, to own a commissioned portrait indicated the owner’s wealth and status because not everyone could afford to have their portrait painted. This portrait of Robert Hooper Jr., painted before the American Revolution, is an image of a successful businessman. His gaze drifts towards the open window – a nod to the source of his wealth, his mercantile and shipping businesses. Hooper grasps a stack of papers in his hands, perhaps a stack of shipping ledgers.

The Hooper family owned the largest and most profitable shipping business in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and therefore had a considerable amount of social and political influence. They were well-known Loyalists, even allowing the British commander-in-chief, and then Massachusetts governor, General Thomas Gage to use their home as his headquarters prior to the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The Hooper family were also vocal supporters of the royally-appointed governor of the Massachusetts colony, Thomas Hutchinson. Most Patriot-leaning colonists had viewed Hutchinson’s performance in office as deplorable, accusing him of pushing a British agenda. He was politically polarized and was identified as the main proponent of the British taxes on the colonies. Yet several men in the Hooper family, including Robert Hooper Jr., lent their names to a published address to Hutchinson lauding his performance in office. The address read as follows:

We, the subscribers, merchants, traders, and others, inhabitants of Marblehead, beg leave to present your our valedictory address on this occasion . . . our most sincere and hearty thanks for the ready assistance which you have at all times afforded us, when applied to in matters which affected our navigation and commerce . . . our sincere esteem and gratitude.. . In your public administration, we are fully convinced that the general good was the mark which you have ever aimed at . . . we beg leave to entreat you, that when you arrive at the court of Great Britain, you would there embrace every opportunity of moderating the resentment of the government against us.

The address was an obvious entreatment to King George III on the part of the colonial merchant class to see that their businesses would not suffer as a result of other colonist’s treasonous activities.

These public declarations understandably did not sit well with the Patriots. Given the already unfavorable sentiments towards Hutchinson and King George, the address had many in an uproar. These statements and other persistent acts of British sympathizing by the Hooper family and other Loyalists families caused them to be subjected to public humiliation and violence. Property was vandalized, and homes were looted and burned. The tensions between the Loyalists and Patriots had reached a boiling point. In order to protect their families and businesses, many who had made the aforementioned statement were forced to publicly recant. Robert Hooper Jr.’s recantation reads as follows:

Whereas I the Subscriber did some Time since sign an Address to Governor Hutchinson, which has given just Offence to my Town and Country: I now declare, that I had not the least Design to offend either, but at the Time of signing said Address I thought it might be of Service to my Town and Country, but finding that it has not had the desired Effect, I do now renounce said Address in all its Parts, and beg that my Town and Country would forgive the Error, and I now assure them that at all Times I have been, and still am ready to the utmost of my Power, to support and defend the just Rights and Liberties of my Town and Country with my Life and Fortune. Robert Hooper, Jun. Marblehead, May 1. 1775.

Like the Hooper family, Copley himself was victimized for his Loyalist sympathies. After hosting a prominent Loyalist at his home in 1774, Copley found an angry mob at his doorstep. Frightened beyond measure for his safety and the lives of his family, Copley chose to sail for England two months later. There the artist was well-received by British society. He soon joined the Royal Academy of Art, and in 1785 was commissioned to paint a group portrait of the three youngest daughters of King George III. Copley would never again set foot in America.

Patriots

Patriots, also known as Whigs, were the colonists who rebelled against British monarchial control. Their rebellion was based on the social and political philosophy of republicanism, which rejected the ideas of a monarchy and aristocracy – essentially, inherited power. Instead, the philosophy favored liberty and unalienable individual rights as its core values. Republicanism would form the intellectual basis of such core American documents as the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

The majority of Patriots were found in the revolutionary hotbed town of Boston. There, prominent figures like Samuel Adams and groups such as the Sons of Liberty fanned the flames of revolution. Taxes like the Stamp Act of 1765 in particular incensed the colonists. The Act required that most printed material in the colonies be printed on specially stamped paper produced in Britain. The printed material, which had to be paid for in British currency, included newspapers, magazines and legal documents. Armed conflict began in April of 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Discussions about independence from the mother country intensified. In June 1776, a committee including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams convened – drafted with the task of writing a formal statement of the colonies’ intentions. Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4 in Philadelphia.

Just two months later in that same city, Charles Willson Peale began the portrait of Mrs. James Smith and her grandson Campbell in September 1776. He finished the portrait months later, after he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Philadelphia city militia. During his time in the militia, Peale was witness to George Washington’s famous crossing of the Delaware River, an event in which Peale deemed “the most hellish scene I have ever beheld,” for the crossing was a dangerous and logistically complicated military maneuver in the middle of an icy winter. Peale, a radical Patriot, was responsible for raising troops and was eventually promoted to captain of the Philadelphia militia.

By the time John Singleton Copley had sailed for England in 1774, Peale’s artistic ability almost matched that of his older colleague. Peale had studied under Copley for a time and had trained in London in the 1760s. Though he had formal training, Peale never attempted the glossy, fanciful refinement which characterizes the work of his fellow London-trained colleagues like Copley. Peale’s style appealed to many, including several of those influential men driving the movement for independence, such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, and Alexander Hamilton. Perhaps it was the simplicity of his style which led William Smith to commission Peale for the double portrait of his mother, Mary, and his son, Campbell.

The Smiths were a family of Irish immigrants who had immigrated to the colonies in the first half of the eighteenth century. William Smith began his career as a merchant in the flour and wheat trade, which began extremely profitable during the war years. He commissioned the portrait of his mother and son in 1776. Peale presents a classic image of youth and promise on one hand, age and wisdom on the other. Using light and shade, Peale delicately explores the individual emotions of each figure, revealing the depth and meaning of the grandmother and grandson’s relationship with one another. The eight-year-old Campbell Smith leans affectionately towards his grandmother and dutifully points out his lesson, Hamlet’s soliloquy, printed in a popular eighteenth century manual for oratorical training, The Art of Speaking. Oratory, the art of formal public speaking, was a highly prized skill in colonial America, particularly for men hoping to go into politics or law. By depicting Campbell reading a book on oratory, Peale indicates the aspirations the boy’s family may have had for his prosperous and successful future.

The Smiths were a family of Irish immigrants who had immigrated to the colonies in the first half of the eighteenth century. William Smith began his career as a merchant in the flour and wheat trade, which began extremely profitable during the war years. He commissioned the portrait of his mother and son in 1776. Peale presents a classic image of youth and promise on one hand, age and wisdom on the other. Using light and shade, Peale delicately explores the individual emotions of each figure, revealing the depth and meaning of the grandmother and grandson’s relationship with one another. The eight-year-old Campbell Smith leans affectionately towards his grandmother and dutifully points out his lesson, Hamlet’s soliloquy, printed in a popular eighteenth century manual for oratorical training, The Art of Speaking. Oratory, the art of formal public speaking, was a highly prized skill in colonial America, particularly for men hoping to go into politics or law. By depicting Campbell reading a book on oratory, Peale indicates the aspirations the boy’s family may have had for his prosperous and successful future.

Primary Source Connections

“In Congress, July 4, 1776, A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General; Congress Assembled,” printed by John Dunlap, Philadelphia, 1776

Read more at the Massachusetts Historical Society

While most people are familiar with the manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the most widely publicly circulated copy looked like this printed version by John Dunlap of Philadelphia in 1776. This copy, in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, is one of only 25 existing copies of the first printing.

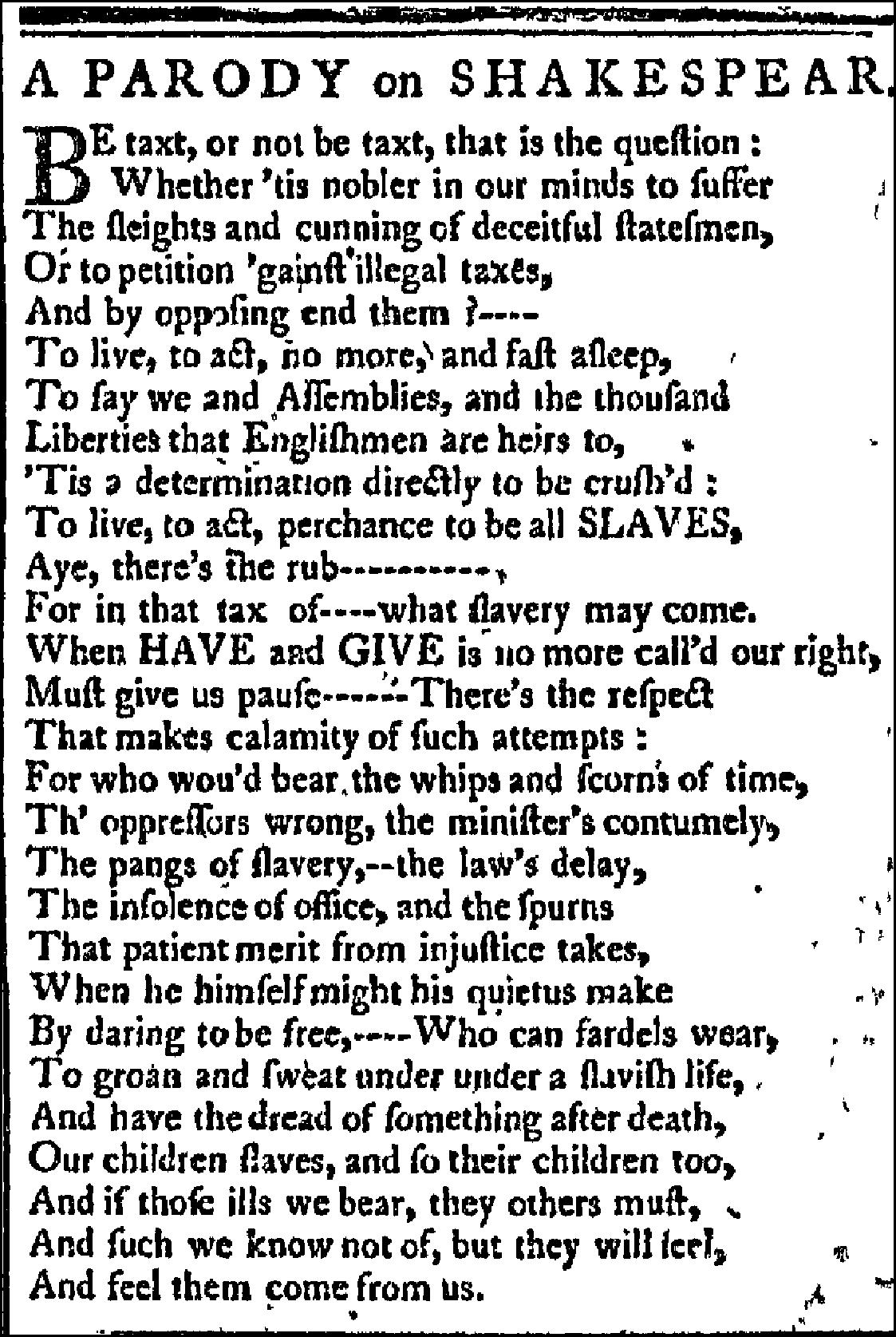

Isaiah Thomas, “A Parody on Shakespear,” August 1770, The Massachusetts Spy

Isaiah Thomas, “A Parody on Shakespear,” August 1770, The Massachusetts Spy

Isaiah Thomas, printer and author of the colonial newspaper The Massachusetts Spy, uses Hamlet’s famous soliloquy to convey his objections over British taxation. Using well known sources to convey new ideas was a popular convention for newspapers in colonial America. The use of the soliloquy in the newspaper corroborates the premise that Charles Willson Peale knew full well what patriotic sentiments the inclusion of the passage in the painting would convey. The following is an excerpt of Thomas’ parody:

Be taxt or not be taxt, that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in our minds to suffer

The sleights and cunning of deceitful statesmen

Or to petition ‘gainst illegal taxes,

And by opposing end them? –

To live, to act, no more, and fast asleep,

To say we and Assemblies, and the thousand

Liberties that Englishmen are heirs to,

‘Tis a determination directly to be crush’d:

To live, to act, perchance to be all SLAVES,

Aye, there’s the rub –

For in that tax of – what slavery may come.

Familiar Letters of John Adams and Abigail Adams During the Revolution, 1876, Charles Francis Adams

Read it at Archive.org

Letter from Abigail Smith Adams to John Adams, July 14, 1776 (Page 201)

Excerpt: “By yesterday’s post I received two letters dated 3d and 4th of July, and though your letters never fail to give me pleasure, be the subject what it will, yet it was greatly heightened by the prospect of the future happiness and glory of our country. Nor am I a little gratified when I reflect that a person so nearly connected with me has had the honor of being a principal actor in laying a foundation for its future greatness. May the foundation of our new Constitution be Justice, Truth, Righteousness! Like the wise man’s house, may it be founded upon these rocks, and then neither storms nor tempests will overthrow it!”

Letter from Abigail Smith Adams to John Adams, July 21, 1776 (Page 204)

Excerpt: “Last Thursday, after hearing a very good sermon, I went with the multitude into King Street to hear the Proclamation for Independence read and proclaimed. Some field-pieces with the train were brought there. The troops appeared under arms, and all the inhabitants assembled there (the small-pox prevented many thousands from the country), when Colonel Crafts read from the balcony of the State House the proclamation. Great attention was given to every word. As soon as he ended, the cry from the balcony was, “God save our American States,” and then three cheers which rent the air. The bells rang, the privateers fired, the forts and batteries, the cannon were discharged, the platoons followed, and every face appeared joyful. Mr. Bowdoin then gave a sentiment, “Stability and perpetuity to American independence.” After dinner, the King’s Arms were taken down from the State House, and every vestige of him from every place in which it appeared, and burnt in King Street. Thus ends royal authority in this State. And all the people shall say Amen.”

Literary Connections

Common Sense, 1776, Thomas Paine

Common Sense, 1776, Thomas Paine

Read it at Project Gutenberg

The case for revolution was starkly established by Thomas Paine who in January 1776 anonymously published Common Sense. In this brief pamphlet, Paine boldly articulates the need for revolutionary fervor and the intellectual underpinnings for what would become the American Revolution. The ideas he articulates had been percolating in the colonies for several decades. Paine’s skill in articulating revolutionary sentiment proved both convincing and compelling. His simple and rational arguments focused the blame for the colonies troubles on King George III and articulated the advantages of independence. More than half a million copies appeared in the colonies within the first year of the pamphlet’s publishing. Without a doubt, Common Sense helped to turn the tide of sentiment toward revolution.

Artwork Connections

Portrait of General Giles, ca. 1785, Joseph Wright

James Giles had joined the Continental Army prior to 1776, serving under the Marquis de Lafayette. He was with the Marquis when Lord Cornwallis and the British army surrendered at Yorktown in 1781. The insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati is prominently displayed on his jacket, indicating his status as a commissioned member of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. Giles later returned to the legal career he left behind in order to serve in the military.

Matthias and Thomas Bordley, 1767, Charles Willson Peale

Matthias and Thomas Bordley, 1767, Charles Willson Peale

Charles Willson Peale’s tender portrait of Matthias and Thomas Bordley presents the young sons of John Beale Bordley, Peale’s early patron. This oval miniature is a reminder that such keepsakes were often painted to comfort the owner in the absence of the people portrayed. Bordley’s sons had just arrived in London to be educated at Eton, under the watchful eye of a family friend. Here, Peale shows them with a bust of Minerva, Roman goddess of wisdom, with a view of St. Paul’s Cathedral in the background. Bordley had paid to send Peale to study in England, and during this trip the artist painted this miniature to give to the boys’ parents in Maryland.

Helen Brought to Paris, 1776, Benjamin West

Benjamin West was in a complicated position as painter to King George III. He was an American who had made his reputation with classical scenes painted for English aristocrats and royalty. Yet, in a court ruled by strict etiquette, West and the king had many frank conversations about the tensions brewing in the American colonies. The union of Helen and Paris led to the Trojan war, and the shadow falling over Cupid’s face at the center of this painting may reflect West’s fear of war between the monarch and his subjects across the Atlantic.

Nathan Hale, 1890, Frederick MacMonnies

Nathan Hale (1755–1776), a teacher from Connecticut, fought for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. The British hanged the twenty-one-year-old soldier as a spy after he had infiltrated their lines in New York. Just before his death, Hale allegedly uttered the now famous words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” Frederick MacMonnies portrayed Hale as a young American martyr. He stands with his shoulders thrust back and his head lifted slightly, even though his feet and arms are bound with rope.

Media

Costs of the American Revolution (3 min)

Scholar Andrew Robertson discusses the costs of the American Revolution from three viewpoints: that of the British, the Loyalists, and the new Americans. From The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

“Approaching Research: Mrs. James Smith and Grandson“(PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

“Approaching Research: Robert Hooper” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

Subject: History

The Price of Freedom: War of Independence – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Americans went to war to win their independence from Great Britain. Just weeks after the outbreak of fighting at Lexington and Concord, Congress appointed George Washington general and commander in chief of an army “for the Defense of American Liberty.” Outmatched American troops often retreated, but returned to fight again, frustrating British efforts to crush the rebellion. A stunning American victory at Yorktown sapped Britain’s will to fight. This online exhibition provides historical essays paired with primary resources.

Lesson Plans

In Defense of Liberty: The Magna Carta in the American Revolution – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Through careful examination of an image of a 1775 Massachusetts thirty-shilling note from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History collections, students will discover the reason Paul Revere featured the Magna Carta (1215) on the currency he designed, and the symbolic importance the document had for American colonists fighting for their “just rights and liberties” as Englishmen.

Glossary

Alexander Hamilton: (1755/57-1804) American statesman and Founding Father of the United States.

Battles of Lexington and Concord: (April 19, 1775) the first military engagements of the American Revolution.

Bill of Rights: a formal statement of the fundamental rights of the people of the United States. It is incorporated into the U.S. Constitution as Amendments one through ten.

Charles Willson Peale: (1741-1827) American painter, soldier, inventor, scientist, politician, and naturalist. He is best known for his portraits of prominent figures of the American Revolution, such as George Washington.

Declaration of Independence: the fundamental document establishing the United States as a nation, adopted on July 4, 1776. The declaration was ordered and approved by the Continental Congress, and was written largely by Thomas Jefferson.

George Washington: (1732-1799) 1st President of the United States, Founding Father, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. Known as the “father of his country” during his lifetime.

John Hancock: (1737-1793) American statesman, merchant, and prominent figure of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and as the first governor of Massachusetts.

John Singleton Copley: (1738-1815) Loyalist American painter, active in colonial America and England.

King George III: (1738-1820) King of Great Britain and Ireland, he is most well known as the presiding monarch during the American Revolution.

Loyalists: colonists of the American revolutionary period who supported, and stayed loyal, to the British monarchy.

Patriots: colonists who rebelled against British control during the American Revolution.

republicanism: the social and political philosophy which rejected the ideas of a monarchy and aristocracy and favored liberty and unalienable individual rights.

Samuel Adams: (1722-1803) American statesmen, ardent Patriot, and Founding Father. He is often credited with being the founder and leader of the Sons of Liberty.

Sons of Liberty: a paramilitary political organization formed in 1765 to protect the rights of colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. Originally a secret society, they were the masterminds behind the Boston Tea Party.

Stamp Act of 1765: an act passed by the British Parliament on March 22, 1765; the first direct tax on the colonies, which required all American colonists to pay a tax on every piece of printed paper, which included items such as newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards.

Thomas Hutchinson: (1711-1780) The British-appointed Loyalist colonial governor of Massachusetts from 1769-1774. He was a proponent of the much–hated British taxes. He was replaced as governor in 1774 by General Thomas Gage and soon after went into exile in England.

Thomas Jefferson: (1743-1826) 3rd President of the United States, Founding Father, author of the Declaration of Independence, and American lawyer. Jefferson oversaw the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France and arranged for the exploration of that territory by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

U.S. Constitution: the document which embodies the fundamental laws and principles by which the United States is governed. It was drafted by the Constitutional Convention and was later supplemented by the Bill of Rights and other amendments.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 3 – Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

- Standard 1A – The student understands the causes of the American Revolution

- 5-12 – Reconstruct the chronology of the critical events leading to the outbreak of armed conflict between the American colonies and England.

- 9-12 – Reconstruct the arguments among patriots and loyalists about independence and draw conclusions about how the decision to declare independence was reached.

- Standard 1B – The student understands the principles articulated in the Declaration of Independence.

- 5-12 – Explain the major ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence and their intellectual origins.

- 9-12 – Draw upon the principles in the Declaration of Independence to construct a sound historical argument regarding whether it justified American independence.

- 5-12 – Explain how key principles in the Declaration of Independence grew in importance to become unifying ideas of American democracy.

- Standard 2C – The student understands the factors affecting the course of the war and contributing to the American victory.

- 5-12 – Compare the revolutionary goals of different groups—for example, rural farmers and urban craftsmen, northern merchants and southern planters—and how the Revolution altered social, political, and economic relations among them.