Construction of the Dam (study for mural, the Department of

the Interior, Washington, D.C.), detail, 1938, William Gropper

The unemployment of many Americans after the crash of 1929 was a demoralizing blow. The emotional toll on the family is depicted in the painting Relief Blues. Families faced humiliation when applying for federal aid, for the aid was only granted after a long and invasive investigation into personal assets and finances. But the country would soon pull itself out of the Depression. A construction-themed mural study depicts the triumph of the American spirit through hard work, ingenuity and perseverance. This construction of the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal economic programs, intended to provide the nation with relief, recovery and reform. The benefits of these programs were two-fold; the jobless were provided jobs, and these jobs were attached to projects that benefited the American people; much like the dam which provided the public with both power and irrigation and jobs for the construction workers. Many artists at the time, including the mural’s artist William Gropper, were employed by New Deal economic programs to embellish public buildings.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Relief Blues

Artist make choices in communicating ideas. What information can we learn about the experience of a family applying for government assistance during The Great Depression? What clues does artist O. Louis Guglielmi give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Is this home?

We see four people and a few simple furnishings in this interior. The space feels cramped with barely enough space to sit around the table and a bed crammed into a corner of the back room. A small stove, prominently placed in the foreground of the painting, does little to warm this shelter with its somber colors and lack of pictures, mementos, or other signs of family life.

We see four people and a few simple furnishings in this interior. The space feels cramped with barely enough space to sit around the table and a bed crammed into a corner of the back room. A small stove, prominently placed in the foreground of the painting, does little to warm this shelter with its somber colors and lack of pictures, mementos, or other signs of family life.

Was it always this way?

Two light pink roses decorate the edge of the floor cover. Their delicacy and beauty seem as though they belong to another world. Perhaps these furnishings once filled a more spacious, more comfortable home.

Why so glum?

Guglielmi painted the most expressive features of these people – their hands and faces – especially large. The viewer can clearly see figures’ expressions and actions, or lack thereof. The mother, usually so busy in a home, stares despondently out of the painting. She is not doing housework, perhaps because she has little to work with in her sparse surroundings. The daughter puts on her lipstick – is she trying to ignore the situation around her or to “put her best face forward” under difficult circumstances? The father looks at the visitor and holds one hand to his chin. As the traditional family provider, his hands are strangely idle. The visitor, still in her coat and hat, leans towards the father as though listening to him, as she writes on a sheet of paper. The heaviness of her posture and expression suggest that she is burdened by sadness or despair.

Guglielmi painted the most expressive features of these people – their hands and faces – especially large. The viewer can clearly see figures’ expressions and actions, or lack thereof. The mother, usually so busy in a home, stares despondently out of the painting. She is not doing housework, perhaps because she has little to work with in her sparse surroundings. The daughter puts on her lipstick – is she trying to ignore the situation around her or to “put her best face forward” under difficult circumstances? The father looks at the visitor and holds one hand to his chin. As the traditional family provider, his hands are strangely idle. The visitor, still in her coat and hat, leans towards the father as though listening to him, as she writes on a sheet of paper. The heaviness of her posture and expression suggest that she is burdened by sadness or despair.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

O. Louis Guglielmi painted this experience of receiving government relief around 1938 for the government’s Works Progress Administration. The artist himself was on a relief program and he could appreciate the stresses of many of his fellow Americans who needed government assistance in order to survive the Great Depression.

Applying for aid was considered a last resort and a humiliating experience. As part of the process, a case worker would come and inspect a home to ensure that the people living there were truly poor enough to qualify for help. The opened curtain implies that this worker has already inspected the family’s living spaces and the fact that she still wears her coat and hat suggests that the room is still cold in spite of the heater. She completes her paperwork at an empty table, indicating that the family has no food or drink to share with her. Case workers, whose jobs were also part of the aid program, faced the desperate situations of fellow citizens time and again. This painting, completed nearly nine years after initial stock market crash, shows the demoralizing, helpless position that was so common amongst Americans at this time.

Construction of the Dam

Artist make choices in communicating ideas. What information can we learn about the New Deal’s efforts to promote relief and recovery from the clues in this mural? How would an infrastructure project such as building a dam impact Americans in their everyday lives? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Directly in the center of this three-panel, monumental mural is a section of an enormous pipe being hoisted above a canyon. A man on top of it directs his co-workers, who include a surveyor and an engineer scrutinizing blueprints for the project. In the left panel, bravely positioned on the steep, jagged edges of the canyon, men operate air drills. At the right, six men balance themselves on a large steel buttress.

Directly in the center of this three-panel, monumental mural is a section of an enormous pipe being hoisted above a canyon. A man on top of it directs his co-workers, who include a surveyor and an engineer scrutinizing blueprints for the project. In the left panel, bravely positioned on the steep, jagged edges of the canyon, men operate air drills. At the right, six men balance themselves on a large steel buttress.

The artist, William Gropper, emphasized teamwork and physical courage by depicting three separate groups of workers, who labor under the oppressive heat of a southwestern sun. The landscape is rocky and dry; in the background a mountain looms. The image flows across the three-part work, a sun-lit tribute to the American worker as a hero. Gropper deliberately romanticized the scene, showing the men smiling as they put innovative technologies to use to harness the enormous potential power of the water. In the new, industrialized America, he seems to say, technology can conquer anything.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

William Gropper proposed this mural for the Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C. He based the image on visits to the Grand Coulee Dam on the Colorado River. Gropper organized the composition in three parts to accommodate a second-floor lobby wall divided by two marble pilasters. Gropper’s monumental mural illustrates the grand theme of nature submitting to the shaping power of humankind. Each scene represents different phases of construction to show the drama, danger, and massive scale of the dam projects overseen by the government. The depicted Grand Coulee Dam was an inspiring feat of twentieth century engineering. It bettered the lives of millions of people by providing them with electrical power and irrigation for their crops. The dam itself is hardly visible in this mural because Gropper wanted to emphasize the American workers who made it possible; he paid tribute to the courage and strength of the laborers and the country recovered from economic disaster thanks to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal relief programs.

Historical Background

Disaster, Relief, and Recovery

The first rumblings of disaster were heard in September 1929 – stock prices fell, then quickly recovered. On Wednesday, October 23, 1929, more than six million shares changed hands, and about $4 billion in stock value was wiped out. Thursday was worse – more than twelve million shares traded, and by noon, losses had reached $9 billion. The following Tuesday, 16,410,000 shares changed hands. For two weeks, stock prices continued to fall, and by mid-November, roughly one-third of the value of stocks listed in September was lost. It was becoming clear that recovery would be neither swift nor easy, and that company promises of wages and pensions had been ephemeral.

Snow Shovellers, 1934, Jacob Getlar Smith, Smithsonian American Art Museum

In reaction to the stock market crash, President Herbert Hoover met with business leaders during the winter of 1929 and 1930. Hoover’s administration asked businesses to maintain wage levels in the hope that recovery would be swift, but by the end of 1930 it was clear that recovery would be neither swift nor easy. During the 1920s, banks failed at a rate of more than 500 per year. In the first ten months of 1930, America saw 659 bank closures; during the last two months of the year, sixty more, many of them woefully undercapitalized to begin with, closed their doors. During Hoover’s last winter as president, the picture was bleak. Tens of thousands of unemployed lined up at soup kitchens, rode the rails in every direction of the compass hoping to find work, or hitchhiked wherever the roads might take them.

By early 1932, more than ten million Americans were unemployed. Industries such as steel and automobiles which had flourished during the World War I years and fueled the economic boom of the 1920s now came to a virtual halt – the unemployment rate for these industries was as high as fifty percent. Those who held their jobs took shorter hours or reduced wages. Unfortunately President Hoover failed the grasp the direness of the economic crisis and as a result, he was blamed by many Americans for failing to leverage the power of the American government to address the problem. As such, he was soundly defeated for re-election in 1932 by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The New Deal

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, and announced that “with the support and understanding of people themselves” he would end the “unjustified terror which paralyses.” Through Roosevelt’s New Deal – his long series of experimental economic programs – he began to restore the faith of the American people in democratic government. Roosevelt had taken office proclaiming the need for “broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.” His series of economic experiments began in March 1933, when Roosevelt sent to Congress what he rightly assessed as “the most drastic and far-reaching farm bill ever proposed in peacetime,” the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA). Following this, the Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA) was put into effect on May 12, 1933, allotting 500 million dollars to give relief to the states, who could then help their citizens who were in need. Infrastructure and conservation work were also a part of FERA.

Roosevelt created the Tennessee Valley Authority and called for a National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which legitimized the right of workers to unionize. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) put Americans to work, providing them with decent nutrition and training to use new technologies. Two hundred thousand young men put to work on conservation and construction projects, projects improving bridges, roads, and sewers, and refurbishing schools and hospitals. A great part of its success was the understanding that the money distributed was not relief but wages.

William Gropper’s Construction of the Dam, a mural painted for the lobby of the Department of the Interior, depicts the type of infrastructure projects Americans worked on as part of the New Deal. The heroic and powerful nature of this depiction of the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam were meant to inspire fellow American and provide them hope in a time of uncertainty. The construction of the Grand Coulee fit President Roosevelt’s sweeping ambitions for the New Deal: jobs for men on relief, planned prosperity for vast rural regions, new opportunity for the destitute migrant. During a 1934 visit to the Grand Coulee’s remote construction site, FDR declared, “This country, which is pretty bare today, is going to be filled with the homes… of a great many families from other states of the union.”

William Gropper’s Construction of the Dam, a mural painted for the lobby of the Department of the Interior, depicts the type of infrastructure projects Americans worked on as part of the New Deal. The heroic and powerful nature of this depiction of the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam were meant to inspire fellow American and provide them hope in a time of uncertainty. The construction of the Grand Coulee fit President Roosevelt’s sweeping ambitions for the New Deal: jobs for men on relief, planned prosperity for vast rural regions, new opportunity for the destitute migrant. During a 1934 visit to the Grand Coulee’s remote construction site, FDR declared, “This country, which is pretty bare today, is going to be filled with the homes… of a great many families from other states of the union.”

The sheer size of the Grand Coulee makes it both a monument and a metaphor. It is one of the largest concrete structures in the world, with 12 million cubic yards of concrete – enough to pave a transcontinental highway. It is 550 feet tall from top to foundation, though not quite as tall as another famed public-works colossus, the 726-foot-tall Hoover Dam. It is, however, several times more massive – Grand Coulee is a mile long to Hoover Dam’s quarter-mile length. When it was completed, the Grand Coulee Dam’s electricity powered the growth of the Pacific Northwest. President Roosevelt’s dedication message, sent from Washington, D.C., spoke of the Grand Coulee’s power. “A tremendous stream of energy,” FDR wrote, “[will] turn factory wheels to make the lives of men more fruitful. It will light homes and stores in towns and cities.” Interior secretary Harold Ickes’ statement spoke directly to the Grand Coulee’s size: “The dam alone comprises the greatest single structure man has built.”

Today, Grand Coulee is still the United States’ largest hydrogenerator of electric power, supplying electricity to the entire western United States, from Washington State to New Mexico, as well as parts of Canada. It generates 21 billion kilowatt-hours, enough to power 2 million homes for a year. A million visitors a year travel to rural Washington State to visit the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, and the dam remains the greatest monument to the New Deal’s epic remaking of the American landscape.

On June 28, 1934, President Roosevelt spoke to the country about the New Deal programs in one of his famous radio addresses termed “fireside chats.” He told his fellow Americans that his administration had introduced relief “because the primary concern of government dominated by the humane ideals of democracy is the sample principle that in a land of vast resources no one should be permitted to starve. Relief was and continues to be our first consideration . . . direct giving shall, whenever possible, be supplemented by provision for useful and ‘remunerative work.” The President spoke directly to the American people, asking if the New Deal programs had improved their lives.

Many people wrote to the President, replying to these questions. The letters disagree vastly, according the differences in people’s circumstances, backgrounds, and beliefs. Some objected to any relief, while others thought that the New Deal was wonderful, whether or not it helped them personally. Replying to the President’s fireside chat query, one American wrote:

I heard your message to the people last night over the radio and was very much empressed [sic] with it. You asked in your Message are you better off than you were last year? My answer I am sorry to say is, I am not. I have not had very much work in the past year. Another one of your questions was, Is your faith in your own individual future more firmly grounded? To that I am glad to say It most certainly is. If I did not have more faith in the future than I have had in the past three years I don’t know what in the world I would do.

The advent of World War II would bring American’s economy roaring back to life. But in the meantime, the New Deal had rebuilt regional economies and fostered small businesses. It had inserted a notion into the American consciousness that the federal government had a responsibility to ensure the health of the economy and the welfare of its citizens. It patronized the arts and created housing. The New Deal had brought into the fold the rural poor, the marginal immigrant communities in cities, and the elderly and unemployed, and gave them a sense that they too had a stake in the future of the nation.

Art as Relief

Artists on WPA, 1935, Moses Soyer, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Many of the New Deal programs were innovative, even radical, in treating artists, writers, and playwrights as workers deserving of support. This was new in America, where artists since the colonial era had largely been considered marginal “extras” of society. The mid-1930s saw artists brought to the forefront, with New Deal programs created for unemployed artists eligible for government relief. Artists, newly defined by the government as workers, produced an unprecedented number of artworks, literary works, and theatrical performances, launching the careers of many who would fine fame in later years. President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously exclaimed, “One hundred years from now my administration will be known for its art, not for its relief.”

The first New Deal arts program was the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), which was created “to give work to artists by arranging to have competent representatives of the profession embellish public buildings.” This seven month-long program (December 1933 through June 1934) funded 3,750 artists to produce 15,600 artworks at a cost of $1.3 million. Artists were encouraged to portray “the American Scene.” With this minimal guidance, they turned to local and regional subjects and created a picture of the country striving to survive through hard work and true grit. They were inspired by the idea that their art would be displayed in public spaces for broad audiences. President Franklin D. Roosevelt awarded the ultimate honor by selecting thirty-two PWAP artworks to hand in America’s premier public space, the White House. Another 130 paintings hung in the Department of Labor Building, while 451 were displayed in the House of Representatives Office Building. The enormous success of the PWAP spawned other New Deal Arts initiatives, some which lasted into the 1940s.

The better-known successor of the PWAP was the Works Progress Administration (WPA) which ran from 1935 through 1943, spending $12 billion to give jobs to nine million people, with three-fourths of the money going for construction projects. But the WPA took a broad view of “workers,” with special programs devised for writers, musicians, actors, and artists. “Why not?” asked President Roosevelt, when criticized for including all these in his recovery effort. “They are human beings. They have to live.” The WPA helped such young, up-and-coming artists as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and O. Louis Guglielmi who, on relief himself, painted Relief Blues for the WPA in 1937.

This powerful painting documents the harsh conditions and emotional toll on Americans during the Great Depression. The painting’s title suggest that the effects of the Depression were both economic and psychological. When the economy collapsed, all hope seemed lost. Welfare was offensive to many; they wanted jobs instead. Yet many people had to admit that they could not make it on their own and were forced to apply for help from the government. In this painting Guglielmi shows how a family and all of their belongings are crowded into a small urban apartment, which they have probably had to move into to save money. The case worker at the right has come to inspect the home to make sure that what is stated on their relief form is correct. The small coal-fired heater and the case worker’s keeping her coat on, both hint that the family has been unable to afford central heating. All this has been seen and is being recorded by the case worker. This invasion of a family’s home for the purpose of making sure that they were truly in need was widely reported as a humiliating ordeal. In Guglielmi’s painting, the father seems lost in thought, hiding his feelings as if he is unable to cope with the idea of going on relief; the daughter literally puts her best face on the situation as if hiding behind a mask of makeup as she pretends that everything is normal. Only the mother openly looks out to share her sorrow with the viewer. Many found the process of applying for relief humiliating, but had realized that there were simply no other viable options. A clothing seller recounted how his life fell apart after the stock market crash and he had to apply for relief:

This powerful painting documents the harsh conditions and emotional toll on Americans during the Great Depression. The painting’s title suggest that the effects of the Depression were both economic and psychological. When the economy collapsed, all hope seemed lost. Welfare was offensive to many; they wanted jobs instead. Yet many people had to admit that they could not make it on their own and were forced to apply for help from the government. In this painting Guglielmi shows how a family and all of their belongings are crowded into a small urban apartment, which they have probably had to move into to save money. The case worker at the right has come to inspect the home to make sure that what is stated on their relief form is correct. The small coal-fired heater and the case worker’s keeping her coat on, both hint that the family has been unable to afford central heating. All this has been seen and is being recorded by the case worker. This invasion of a family’s home for the purpose of making sure that they were truly in need was widely reported as a humiliating ordeal. In Guglielmi’s painting, the father seems lost in thought, hiding his feelings as if he is unable to cope with the idea of going on relief; the daughter literally puts her best face on the situation as if hiding behind a mask of makeup as she pretends that everything is normal. Only the mother openly looks out to share her sorrow with the viewer. Many found the process of applying for relief humiliating, but had realized that there were simply no other viable options. A clothing seller recounted how his life fell apart after the stock market crash and he had to apply for relief:

I didn’t want to go on relief. Believe me, when I was forced to go to the office for the relief, the tears were running out of my eyes. I couldn’t bear myself to take money from anybody for nothing. If it wasn’t for those kids – I tell you the truth – many a time it came to my mind to go commit suicide. Than go ask for relief. But somebody has to take care of those kids.

Rural America suffered from the economic downturn as well. In 1937, a group of photographers employed by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) set out to create a pictorial record of the impact of hard times on rural America. Eighty thousand documentary photographs were distributed to newspapers and magazines to show the devastation of the Dust Bowl; and grinding poverty on agricultural lands and people, and some were featured in a 1938 exhibition called How American People Live, producing an overwhelming public response that made New Deal programs more popular than ever. Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” and Walker Evans’s Alabama sharecroppers are among these haunting images about profound distress and human dignity. In later years, the program’s photographers documented America’s mobilization effort for World War II. 164,000 FSA photographs are in the Library of Congress collections as an invaluable resource and moving tribute to hard times.

Primary Source Connections

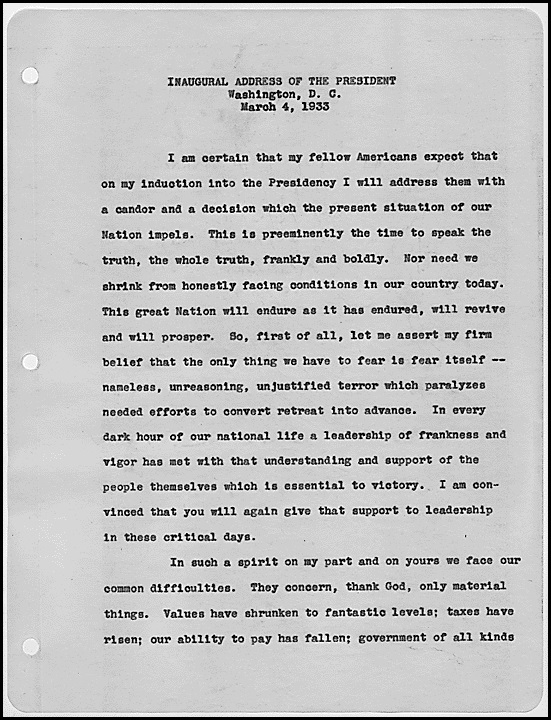

FDR’s First Inaugural Address, 1933

FDR’s First Inaugural Address, 1933

Read it at The National Archives

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s inaugural address to the nation in 1933 was essentially a declaration of war on the Depression. FDR set out to not only reassure the American public, but lay out his plan for recovery. His plan required the expansion of executive power, something for which this address set out to prepare the American public. Roosevelt stated: “Our Constitution is so simple and practical that it is possible always to meet extraordinary needs by changes in emphasis and arrangement without loss of essential form. That is why our constitutional system has proved itself the most superbly enduring political mechanism the modern world has produced. It has met every stress of vast expansion of territory, of foreign wars, of bitter internal strife, of world relations.” Though at the same time, he was prepared to recommend measures that he knew could succeed only with strong public pressure in support of extraordinary federal powers to deal with “extraordinary needs.”

FDR fireside chat on U.S. Supreme Court Reform Plan, 1937, Harris & Ewing (photographer), Library of Congress

Transcripts of FDR’s Fireside Chats

Read it at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

Between March 1933 to June 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the American people in a series of 30 speeches broadcast via radio, speaking on a variety of topics from unemployment to banking to fighting fascism in Europe. Millions of Americans found comfort and renewed confidence in their government through these speeches, which became known as the “fireside chats.”

Of particular importance are:

- On the Bank Crisis – Sunday, March 12, 1933

- Outlining the New Deal Program -Sunday, May 7, 1933

- On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program -Monday, July 24, 1933

- On the Works Relief Program – Sunday, April 28, 1935

- On Economic Conditions -Thursday, April 14, 1938

Literary Connections

Memoir of Arcadia Hernandez Lopez – Chapter 12: The Depression

Memoir of Arcadia Hernandez Lopez – Chapter 12: The Depression

Find it in a Library (Excerpt from page 49)

Excerpt: “Of course, we did not lose any money during the Depression, because we did not have any in the bank or elsewhere to lose. Unemployment became rampant, and the people who continued to work earned a pittance. There were soup lines and many businesses were forced to close. Some teachers were being let go and the rest were paid in script. Times were tough, tough. Few men could afford to get haircuts at my father’s barber shop. Before the Depression, they got shaves also; but now they had safety razors and no money, so many men shaved themselves. Father earned very little during this time. All he could give mother was twenty cents a day to feed the family, which had grown to four children. Mother would buy corn dough and frijoles, and we would have tortillas and beans every day. These were hard times, very hard times. We had always helped Daddy to earn money, but now we had to work even harder. We earned money at home by doing the finishing work on children’s dresses — hems and embroidery — and by shelling pecans. In the summer, we went to pick cotton. That helped to buy clothes and supplies for school. I was ready to go to college, but there was no money to pay the tuition. There wasn’t even enough to take the bus nor to eat at the school cafeteria. So I walked the several miles to school and packed my own brown-bag lunch. Having to walk several miles was not conducive to a happy attitude. When I forgot my lunch, I had to suffer with an empty, aching stomach through classes.”

Source: Barrio Teacher, 1992, Arcadia Hernandez Lopez

Artwork Connections

Automotive Industry (mural study, Detroit, Michigan Post Office), 1940-1941, William Gropper

The artist took pride in his commissions for the Works Progress Administration (including this mural) and believed that, like the workers shown in this mural, he was a valuable member of a working class intent on rebuilding the nation after the Depression. He wrote to officials at the Treasury Department thanking them for “a great pleasure and stimulant” and vowing that “we will continue to do our part in building a great American Art and Culture”

Automotive Industry (mural, Detroit Public Library), 1940, Marvin Beerbohm

The Works Progress Administration commissioned Automotive Industry for a library in Detroit, the automobile capital of the world. Beerbohm celebrated the nation’s industrial might and the sweat of the laborers who made it happen. At the very center of this mural is a cutaway view of an engine, showing the piston arm pushing down and around the crankshaft to turn the wheels. Beerbohm repeated this shape eight times across the span of the image in the muscular arms of the men who build the cars. The different parts and processes of the factory surround these workers who are like the motor’s piston and its connecting arm, at the very heart of the enterprise. The WPA commissioned thousands of images like this, not only to encourage blue-collar workers but to help the nation’s artists feel that they were a vital part of America’s workforce.

Dispossessed , ca. 1938, Mervin Jules

, ca. 1938, Mervin Jules

Mervin Jules’s scenes of the urban homeless showed the desperation of people ruined by the Great Depression. Here, an elderly couple have lost their home and sit in despair among their possessions, out of work, old, and vulnerable. Their long faces and defeated poses express the depth of misery. A tray on the ground reflects a group of workers waiting in line, emphasizing the desperation of the times. Jules was committed to the social purpose of art, and although he confronted difficult issues, a curator described him in 1941 as having “an optimism, tempered with courage to face facts as they are . . . At the core of his optimism is respect for just people and their occupations.”

Tenement Flats, 1933-1934, Millard Sheets

Tenement Flats, 1933-1934, Millard Sheets

These ramshackle tenements were home to poor families in the Bunker Hill neighborhood of downtown Los Angeles during the Great Depression. Millard Sheets, like many artist members of regional committees, proudly gave his painting as a gift to his country. The shabbily dressed women in Tenement Flats would be startled to discover that this painting would hang in the elegant surroundings of the White House. PWAP paintings like this one were displayed in reception areas to show President Roosevelt’s commitment to art and to ordinary Americans across the country.

Snow Shovellers, 1934, Jacob Getlar Smith

Black and white, poor and middle class—all had lost their jobs to the Great Depression. Smith showed them gathered into the ranks of the New Deal social programs that offered them all the means to get through the winter. A boy pulling a sled walks alongside the men, a reminder of the families who looked to these men for their support.

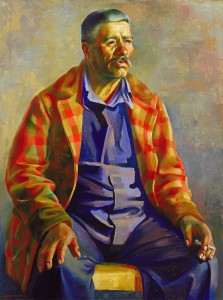

Juan Duran, 1933-1934, Kenneth M. Adams

Juan Duran, 1933-1934, Kenneth M. Adams

Kenneth Adams painted Juan Duran as a proud laborer taking a cigarette break. Duran’s heavy coat and blue overalls underscore his enduring strength and echo the folds around his weary eyes. The artist emphasized Duran’s strong hands by placing them prominently on his knees, reinforcing the value of manual labor. Like many artists of the 1930s, Adams worked for the Works Progress Administration. He and his peers created images that gave dignity to laborers and helped the artists themselves to feel as though they were valued members of the workforce.

Somewhere in America, 1934, Robert Brackman

Somewhere in America, 1934, Robert Brackman

In Robert Brackman’s painting the red-checkered cloth and fruit plate reflect popular ideas of home and heartland in the 1930s, but the girl’s wary expression makes her seem old beyond her years. During the Great Depression, scenes like this were meant to reflect the nation’s strong spirit and to remind Americans of their common bonds rather than their differences. This attitude drove New Deal art projects, which aimed to appeal to broad audiences and affirm shared values. But Brackman’s title suggests that he wanted his viewers to think about a class of Americans who were largely excluded from the optimistic imagery that prevailed.

Golden Gate Bridge, 1934, Ray Strong

Golden Gate Bridge, 1934, Ray Strong

This panoramic depiction of the Golden Gate Bridge under construction pays tribute to the ambitious feat of engineering required to span the mouth of San Francisco Bay. Strong’s painting, with its intense colors and active brushwork, conveys an infectious optimism. Hundreds of tourists who shared the artist’s excitement came to gaze at this amazing project that continued despite the financial strains of the Great Depression. President Franklin Roosevelt chose this painting celebrating the triumph of American engineering to hang in the White House.

Gold Is Where You Find It, 1934, Tyrone Comfort

Gold Is Where You Find It, 1934, Tyrone Comfort

Rising gold prices during the Great Depression caused many old mines to reopen and sent the hopeful across the American West in search of new strikes. When President and Mrs. Roosevelt chose this painting to hang in the White House, it represented a rapidly rising industry helping to fuel the reviving American economy.

Media

The Great Depression: Crash Course US History – PBS (14 min) TV-G

The Depression happened after the stock market crash, but wasn’t caused by the crash. This PBS video will teach you about how the depression started, what Herbert Hoover tried to do to fix it, and why those efforts failed.

The New Deal: Crash Course US History – PBS (15 min) TV-G

This PBS video teaches you about the New Deal, which was president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s plan to pull the united States out of the Great Depression of the 1930’s. The video discusses some of the most effective and best known programs of the New Deal. Also, who supported the New Deal, and who opposed it?

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

Myths in Words and Pictures – Smithsonian Education

The symbolism of Achelous and Hercules features lesson ideas and online interactives.

Subject: History

The Grand Coulee Powers On – Smithsonian Magazine

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s dedication message, sent from Washington, D.C., spoke of the Grand Coulee’s power. “A tremendous stream of energy,” FDR wrote, “[will] turn factory wheels to make the lives of men more fruitful. It will light homes and stores in towns and cities.” Interior secretary Harold Ickes’ statement spoke directly to the Grand Coulee’s size: “The dam alone comprises the greatest single structure man has built.” This article tales a look back at how the powerful dam came to be.

Glossary

Agricultural Adjustment Act: (AAA) a 1938 New Deal era law which reduced agricultural production by paying farmers subsidies to not plant part of their land in order to reduce crop surplus, therefore effectively raise the value of crops.

Civilian Conservation Corps: (CCC) a New Deal public relief program which employed young men (ages 17-28) to work on conservation projects including the construction of roads, bridges, and dams and the reforestation of nearly 3 million trees to combat the effects of the Dust Bowl.

Dorothea Lange: (1895-1965) American documentary photographer and photojournalist. She is best known for her pioneering Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

Farm Security Administration: (FSA) created in 1935 as part of the New Deal, the administration was created to combat rural poverty during the Depression.

Federal Emergency Relief Act: (FERA) 1933; the first governmental action to combat the Depression, the act allotted 500 million dollars to the states in order to provide for the needy and the unemployed.

fireside chats: a series of 30 radio conversations, or chats, given by President Franklin D. Roosevelt from 1933 to 1944. The phrase “fireside chat” was coined in order to evoke an image of the president sitting by a fire in a living room speaking to the American people, seemingly “one on one,” to provide them with hope and reassurance during the worst economic crisis in American history.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: (1882-1945) 32nd President of the United States, commonly known by his initials, FDR. He is best known for his series of social programs, called the New Deal, which focused on relief, recovery, and reform to combat the effects of the Great Depression. He won a record four presidential elections, which led to the passage of the 22nd Amendment, barring presidents from serving more than two full terms.

Herbert Hoover: (1874-1964) 31st President of the United States. Hoover took office in 1929, the year the American economy plummeted into the Great Depression. Unfortunately Hoover failed the grasp the direness of the economic crisis and as a result, he was blamed by many for failing to leverage the power of the American government to address the problem. As such, he was soundly defeated for re-election by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Jackson Pollock: (1912-1956) American painter and major figure of the Abstract Expressionist movement. He is best known for his iconic “drip” paintings.

Mark Rothko: (1903-1970) American painter and major figure of the Abstract Expressionist movement, although he refused to self-identify as such.

New Deal: (1933-1938) a series of domestic social programs and projects enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in an effort to combat the crippling effects of the Great Depression. These programs included immediate economic relief, as well as reforms in industry, agriculture, and labor.

National Industrial Recovery Act: (NIRA) passed by Congress in 1933, the Act authorized the President regulate industry in an attempt to regulate prices and stimulate economic recovery.

Public Works of Art Project: (PWAP) a program established to employ artists during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal series of social programs. The program ran from 1933 to 1934.

stock market crash: the severe downturn in stock prices which occurred during a two week period, beginning on October 29, 1929. The crash, while not the sole cause of the Great Depression, heralded the beginning of the Depression.

Tennessee Valley Authority: a federally owned corporation established in 1933 to construct dams and power projects in the Tennessee Valley – an area particularly hard hit by the Depression.

Works Progress Administration: (WPA) the largest New Deal agency that employed millions of people to carry out public works projects. These projects included roads, public buildings, bridges, dams and more.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 8 – The Great Depression and World War II

- Standard 1A – The student understands the causes of the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.

- 5-12 – Analyze the causes and consequences of the stock market crash of 1929.

- 5-12 – Evaluate the causes of the Great Depression.

- 7-12 – Explore the reasons for the deepening crisis of the Great Depression and evaluate the Hoover administration’s responses.

- Standard 1B – The student understands how American life changed during the 1930s.

- 7-12 – Analyze the impact of the Great Depression on industry and workers and explain the response of local and state officials in combating the resulting economic and social crises.

- 7-12 – Analyze the impact of the Great Depression on the American family and on ethnic and racial minorities.

- 9-12 – Explain the cultural life of the Depression years in art, literature, and music and evaluate the government’s role in promoting artistic expression.

- Standard 2A – The student understands the New Deal and the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

- 9-12 – Contrast the first and second New Deals and evaluate the success and failures of the relief, recovery, and reform measures associated with each.

- Standard 2B – The student understands the impact of the New Deal on workers and the labor movement.

- 5-12 – Explain how New Deal legislation and policies affected American workers and the labor movement.