Homer Dodge Martin’s Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York depicts a cliff riddled with mine shafts stained red by the oxidized iron ore seeping down its side resembling bleeding wounds; an apt metaphor for the horrors of the Civil War. During the war, the North’s primacy lay in its resources and manufacturing ability to lie down railroads to move men, arms and supplies faster and farther than the South – an advantage that helped the North win the war. As we approached the last quarter of the nineteenth century, America transitioned into the era of the Industrial Revolution. The first steamboats designed by Robert Fulton made their debut transporting agricultural and industrial supplies and products on American canals and rivers in the nineteenth century. Ports were busy with commerce, importing and exporting. Factories were in full swing twelve hours a day, six days a week, producing goods for a rapidly expanding population. But by the 1870s, railroads had replaced waterways as America’s main mode of transportation. Samuel Colman’s landscape depicts the transition into the Industrial era in his image of a steam boat gliding across the Hudson River near Storm King Mountain. The rustic rowboat in the foreground serves to contrast the steam boat and as a reminder of days past and the evolution of technology. The dawn of the industrial age provided fuel for artists –offering them exciting new scenes to paint like mines, railroads, and steam transportation.

Download a Teaching Poster PDF of Storm King on the Hudson

Activity: Observe and Interpret

The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York

What can we learn about America, a year into the Civil War, from this painting by Homer Dodge Martin? How does the landscape reveal the nature and hardship of war? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

What do you notice about the mountain? What are the holes in it and the streaks below them?

This mountain dominates the painting, taking up two-thirds of the canvas. The round openings in the mountain are mine shaft entrances. The red streaks below the entrances are tailings, or drainage, from the mine shafts. In this case, leftover ore has oxidized, turning the tailings a rusty red color.

What’s happened to the landscape?

We can tell from the mineshaft openings and tailings that this was once a mine, but all the scaffolding and mining equipment that would be at an active mine site are gone. This mine has been abandoned. Contrast the small cascading stream of water, lush woods, and natural boulders on the left side of the painting with the tailings, sparsely forested land, and fragmented rock at its center. Even after it was abandoned, the mining operation left permanent scars across the landscape.

We can tell from the mineshaft openings and tailings that this was once a mine, but all the scaffolding and mining equipment that would be at an active mine site are gone. This mine has been abandoned. Contrast the small cascading stream of water, lush woods, and natural boulders on the left side of the painting with the tailings, sparsely forested land, and fragmented rock at its center. Even after it was abandoned, the mining operation left permanent scars across the landscape.

How is the waterway an important part of this picture?

Canal boats on the river, like the one in this picture, were used to transport mined materials from the site of natural resources to foundries where they were forged into parts. Iron, from mines like this one, was originally used in railroad construction. However, during the Civil War, iron shipments were diverted to the West Point Foundry, further south on the Hudson River, and used in making powerful artillery for the Union army.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Homer Dodge Martin painted this abandoned iron mine along the Hudson River in 1862 when the United States was in its second year of the Civil War. Unlike the Confederacy, the Union had natural iron reserves with which to build and resupply its war arsenal. By focusing on this advantage of natural resources, Martin may be asserting the primacy of the North’s position in the War. This landscape also reflects the harsh and lasting damage of war. Martin would have seen graphic photographs of the battle of Antietam while he was painting this work. The Civil War marked the first time that the public saw vast images of actual battlefields and such images profoundly impacted the way the pubic viewed war. The mineshaft entrances and tailings on this mountain metaphorically speak to the bullet holes and bloodshed of the war. This landscape, like the country, is stripped, damaged, and its future uncertain.

Storm King on the Hudson

What can we learn about life on the Hudson River as industrialization began to change the way Americans traveled and traded upon its waters? How does the artist’s juxtaposition of manmade and natural elements reflect his view of the world around him? Would we share his perspective today? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

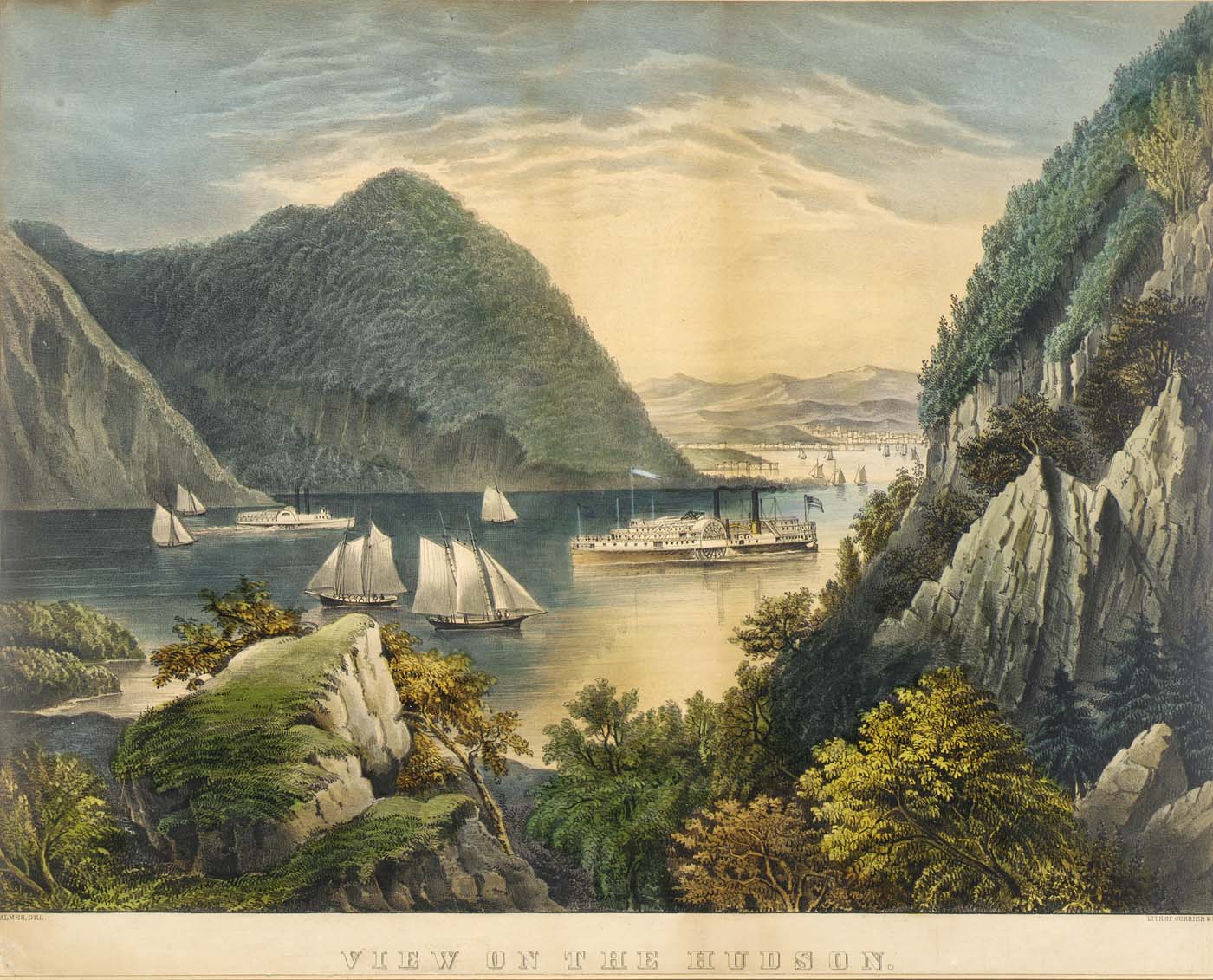

Samuel Colman’s painting depicts what was a common sight on the Hudson River: a formation of boats and barges below Storm King Mountain in Cornwall, New York.

The left half of the painting represents the country’s industrialized future, roaring back to life after the Civil War. It is the dawn of America’s transportation revolution. Large commercial barges are linked together to form a tow for canal boats, their huge paddle wheels turned by coal-generated steam. On the right side, we see an older way of life on the river, with sail boats hugging the shore. Two small fishing boats in the foreground work in tandem, each having one end of a seine, or fishing net. The seine connects the two halves of the composition underwater; a connection not visible from the surface, it figuratively stitches together the past and the future. All of the watercraft depicted in Colman’s composition sailed between Albany and New York City on the Hudson River, transporting cargo such as coal southbound to New York City, and passengers northbound to Albany.

Huge puffs of steam and smoke fill the upper left corner of the painting, billowing from the powerful engines of the steamboats, contrasting with the heavy cloud cover hovering over the aptly named Storm King Mountain. Storm King, the highest mountain in the Hudson Highlands, dominates the background of the painting. The area around it was known for quickly changing winds and highly charged thunderstorms. Colman gives nearly a third of the height of his canvas to these impressive clouds.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

What can we learn from this painting about life on the Hudson River in 1866? What clues does it give us to changes to come?

With the Civil War over, a building boom began and there was an expanded need for the transportation of goods and materials. The Hudson River served as an important waterway for the transportation of goods and passengers. In light of industrial and technological advances, older modes of transportation, like sailing vessels, were replaced by more efficient ones, like steamboats. However, in 1866, all these vessels shared the river. Coleman divided the natural and man-made elements of his painting into two halves, alluding to the coming conflict when industry would steadily overtake the environment.

In the years following this painting, industry along the river further increased. The river was both polluted and overfished. The scenic Storm King Highway was cut into the side of the great mountain. Railways joined steamboats for transporting freight and passengers. A century after this painting, plans for a hydroelectric power plant threatened the site of Storm King in the 1960s and the mountain became a symbol for citizens concerned about the environment. The efforts of these Americans, including folk singer Pete Seeger, led to such legislation as the Environmental Policy Act and Clean Water Act, as well as environmental education programs that continue to this day.

Historical Background

How the Railroad Won the War

The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York, (detail) ca. 1862, Homer Dodge Martin, Smithsonian American Art Museum

During the Civil War, some artists used the landscape as a metaphor for the horrors of war. In this context, red-orange iron ore streaming from gaping mineshafts like bleeding wounds becomes representative of the bullets which riddled men, forests, and homesteads during the war. The damaged landscape echoes the corpse-strewn battlefields seen in photographs of particularly bloody battles like Antietam. Port Henry’s abandoned iron mines become yet another casualty of the war, much like the men who fought on the battlefield and the towns and homesteads that were leveled by the armies of Generals Grant and Sherman in the South

Yet not all landscape paintings produced during the Civil War represented our country’s wounds. Another reading of The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York is that the iron ore is representative of the strength of the Union Army. Homer Dodge Martin’s painting asserts the primacy of the North, whose strength lay in its natural resources and manufacturing. Iron played a crucial role in the Union victory. The mines at Port Henry tapped one of the richest veins in the northeast, and supplied much of the iron used to create the country’s rail lines in the 1850s.

Railroads were effective, reliable, and faster modes of transportation, edging out competitors such as the steamship. They traveled faster and farther, and carried almost fifty times more freight than steamships could. They were more dependable than any previous mode of transportation, and not impacted by the weather. Perhaps most importantly to those with an eye on government finances during the war, their direct routes and dependable scheduling reduced the cost of transportation by nearly ninety-five percent, freeing capital for other uses.

The North had a greater advantage over the South in terms of its human, natural, and industrial resources, but it was the effective application of these resources which provided the greatest windfall for the Union. The Union Army’s capitalization and strategic use of the railroad played a direct role in helping the North win the war.

The Tactical Importance of the Railroads

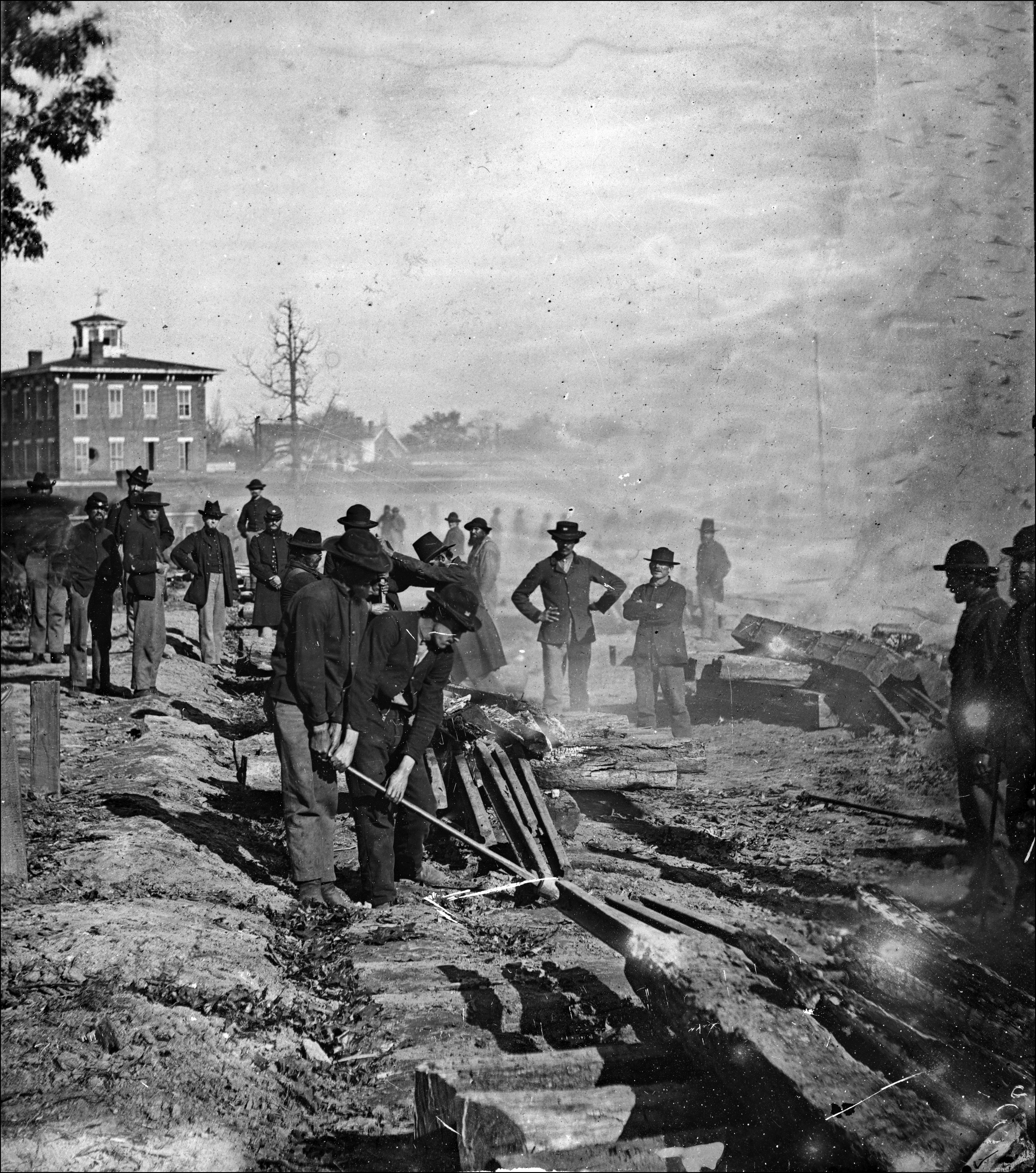

Atlanta, Georgia, Sherman’s men destroying railroad, 1864, George N. Barnard, Library of Congress

The Civil War was different from previous conflicts as it was, in a sense, the first modern war. Previous battles, like those of the Revolutionary War, had been fought in or near populous areas to take advantage of local resources. Where a battle was fought was dependent on the availability of these resources. Armies moved constantly so as to not exhaust one area’s supply. But with the advent of the railroad battles no longer needed to be waged so close to urban areas. The majority of Civil War battles were fought outside populated areas, in what were then remote and underdeveloped areas of the country, primarily in southern states like Mississippi, Tennessee, and Georgia. Every major Civil War battle east of the Mississippi River took place within twenty miles of a rail line. Railroads provided fresh supplies of arms, men, equipment, horses, and medical supplies on a direct route to where armies were camped. The railroad was also put to use for medical evacuations, transporting wounded soldiers to better medical care. Consequently, armies were not dependent on the bounty, or lack thereof, of the land which they occupied.

Railroads were visible symbols of industry and modernity during the Civil War. They were agents of progress, promoters of civilization, and enhancers of democracy which could bind the North and the South together as one nation. They were also the lifeline of the army. A general’s success or failure depended on fresh supplies and soldiers delivered directly to the battlefield. Consequently, Union strategists deliberately targeted rail junctions as campaign objectives in places like Chattanooga, Tennessee; Atlanta, Georgia; and Corinth, Mississippi. This was especially true of Atlanta, a city which served as the Confederacy’s rail hub and manufacturing center.

Railroads became a set of guidelines between which campaigns were waged, battles were fought, and men and materials were moved. A commander’s understanding of the rail network became key to managing operations and informing tactical decisions. Arguably, no Civil War commander used the rail network to their advantage quite like Union General William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman elucidated on the importance of the railroad for the Union during the Atlanta campaign:

Four such groups of trains daily made one hundred and sixty cars, of ten tons each, carrying sixteen hundred tons, which exceeded the absolute necessity of the army, and allowed for the accidents that were common and inevitable. But, as I have recorded, that single stem of railroad, found hundred and seventy-three miles long, supplies an army of one hundred thousand men and thirty-five thousand animals for the period of one hundred and ninety-six days, viz., from May 1 to November 12, 1864. To have delivered regularly that amount of food and forage by ordinary wagons would have required thirty-six thousand eight hundred wagons of six mules each, allowing each wagon to have hauled two tons twenty miles each day, a simple impossibility in roads such as then existed in that region of country. Therefore, I reiterate that the Atlanta campaign was an impossibility without these railroads; and only then, because we had the men and means to maintain and defend them, in addition to what were necessary to overcome the enemy.

Following the Battle of Atlanta, as Sherman’s army moved east to begin the Savannah Campaign (commonly referred to as the March to the Sea), his railroad men destroyed all of the rail lines that led back to Chattanooga, Tennessee so as to deny a vital supply line to the Confederates. This railway destruction tactic was referred to as Sherman’s neckties. The rails were heated and then bent into a loop around the trunks of trees, in the shape of a necktie, so that they could not be easily or quickly repaired. This was such an important tactic that Sherman made it a point to oversee it himself:

The whole horizon was lurid with the bonfires of rail-ties, and groups of men all night were carrying the heated rails to the nearest trees, and bending them around the trunks. Colonel Poe had provided tools for ripping up the rails and twisting them when hot; but the best and easiest way is the one I have described, of heating the middle of the iron-rails on bonfires made of cross-ties, and then winding them around a telegraph-pole or the trunk of some convenient sapling. I attached much importance to this destruction of the railroad, gave it my own personal attention, and made reiterated orders to others on the subject.

Destroying the Confederacy’s railroads took away another advantage the South had over the North – land mass. By shrinking the vast space the Confederate Army could operate within, the Union was able to contain the Confederate army to a much smaller, and much more vulnerable, piece of land. This cost the South its use of interior lines, crippling the ease with which they had been able to move troops from point to point by railroad and attain victories.

Northern versus Southern Railroads

The South’s reliance on a primarily agrarian economy, coupled with a modest manufacturing base, meant that there was limited demand for rail service in the Confederacy. Less capital had been invested and as a result the rail network in the South was in poor condition, having been manufactured during the early years of railroad development when significant improvements had not yet been made. Since manufacturing was more dominant in the North, the Union had access to a disproportionate amount of foundries compared to the South.

The rails of the day were made from relatively soft iron which often broke or would wear away after continued use. Northern foundries began to experiment with stronger and more durable iron products such as steel. But the southern foundries had difficulty purchasing the necessary supplies for diligent upkeep of their rail lines, and as a result, the infrastructure of southern rail lines gradually crumbled. It has been estimated that during the Civil War, southern foundries could only manufacture 16,000 tons of railroad iron per year, yet 50,000 tons was required to adequately repair their deteriorating rail lines. To contrast that number, Pennsylvania foundries alone produced almost 270,000 tons of iron in 1860. Consequently even before war broke out, the South purchased most of their iron from Northern foundries. After the war began, the South outsourced, purchasing iron from Europe. However, the Union navy did their best to prevent this.

Southern rail lines also suffered from disconnect due to change in gauge, something that had happened as the rail networks evolved over time. North Carolina and Virginia shared the same type of gauge, standard gauge, yet the rest of the Confederate rail system operated on broad gauge. This disconnect kept much of the South isolated. Freight would have to be offloaded to another mode of transport, usually a wagon train, and then re-loaded onto another locomotive. Standardizing the gauge throughout the system during the war was not an option for the South, which lacked the time, money, and supplies to do this successfully. Once the North had captured a Southern rail line, it was effectively cut off from the rest of the network and rendered useless.

The Transportation Revolution

The expansion of internal American trade greatly increased with the adoption of canals, steamboats, and railroads. These collective advances in technology became known as the Transportation Revolution. This increase in American industrialization in the nineteenth century became a major cause for the rapid settlement of the West. The economic development and stability of the western states depended on their capability to export farm products in exchange for imports from the eastern states such as sugar, coffee, and salt. Yet transportation was costly and time-consuming, with methods limited to sailing vessels and perilous overland trails. The successive developments of the steamboat, the canal system, and the steam-powered locomotive alleviated the cost and time of the journey, produced growth in manufacturing, encouraged western settlement, and led to increased foreign trade.

Early Sailing Vessels

In Storm King on the Hudson, Samuel Colman depicts a period of time during the mid-nineteenth century where schooners, sloops, and steamships operated simultaneously on the Hudson River. The inclusion of both old and new methods of river transportation suggests the passage of time, when man-powered rowboats and sailing vessels were giving way to steamships. Two sailing vessels are depicted on the river at the base of Storm King Mountain, near the shore at Cornwall Landing. The sailing vessel on the left of the painting is a sloop, while the vessel on the right is a schooner. The sloop a sailing vessel commonly used one hundred years earlier, in the middle of the eighteenth century. By 1850, shipbuilders had perfected a distinct type of sailing ship adapted for Hudson River navigation. This boat, known as the Hudson River or North River sloop (the North River was another name for the Hudson), was the pre-eminent vessel in Hudson River shipping and trade for 150 years and continued to be used for transportation more than a half-decade after the introduction of steamships in the early nineteenth century.

View of the Hudson, ca. 1865, Frances Flora Bond Palmer, color lithograph, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Colman has included a later version of a Hudson River sloop in Storm King, visible as the second sailing vessel on the right near the shoreline. These early sloops were solidly-built, and weighed 60-80 tons. They were wide with plenty of room for cargo and had a shallow hull design that allowed the boat to navigate shallow areas of the river. Sloops carried both cargo and passengers. With the development of agriculture and timbering in the Hudson River Valley and areas further north, the sloops carried cargo down the river to the burgeoning Port of New York. They carried grain, produce, flour, hay, lumber, and fur pelts. When these bulky cargoes were unloaded at New York City or ports along the way, this freed the vessel to carry passengers northward on the return trip to Albany and points along the way. In the early nineteenth century, the average Hudson River sloop could carry 25 to 30 passengers. The sloops also transported manufactured goods for sale up the river, including rum, hardware, fabrics, and luxury goods. Sloop owners often placed newspaper advertisements soliciting freight consignments and announcing the arrival of goods for sale in a particular port. But sloops could not compete with schooners, which came to monopolize the Atlantic coastal trade.

The numbers of sloops built began to decline around 1855 due to the competition from the schooner. Larger than sloops, the two-masted schooners had the advantage of being easier to sail than the sloops and they could be easily managed with a small crew of only 3 to 4 people. Sloops had always had difficulty navigating the stretch of the river below Storm King Mountain, because the massive form of the mountain blocked the flow of air onto the river and sloops were often stranded and had to sit at anchor until the wind changed. The schooner’s individual sails covered less area and therefore were lighter and easier to furl and unfurl.

Steamboats Replace Sailing Vessels

While sloops and schooners were vying for supremacy on America’s eastern rivers, another type of vessel was slowly developing, one that would transform the shipping industry. Sloops and schooners were adequate enough, but they had major disadvantages. Both were relatively slow and their speed (and consequently how fast their cargo could get to port) depended entirely on wind power. Enter American artist-turned-inventor/ engineer Robert Fulton (1765-1815). Fulton began his career in portrait painting, studying in London with Benjamin West, where he had the opportunity to paint Benjamin Franklin’s portrait. Despite this high profile commission, it was not enough to guarantee success in the arts. Consequently Fulton turned his efforts to another interest – canal and shipbuilding.

It is a common misconception that Fulton was the inventor of the steamboat, but it was Fulton who was instrumental in making steamboat travel a reality, transforming it from mere concept to actuality. Along with his financial partner Robert Livingston, Fulton built upon knowledge gleaned from years of experimenting with different designs in England and France to finally develop and build a working steamboat in the United States. In August 1807, his steamboat made its historic voyage navigating the Hudson River from New York to Albany. The trip took an incredible thirty-two hours. By comparison, the same trip took sailing vessels four days to complete.

Livingston, who had helped engineer the Louisiana Purchase during President Thomas Jefferson’s administration, saw the potential for the use of steam power on the mighty Mississippi River. Livingston commissioned Fulton to design the New Orleans, the first steamboat in America to sail on waters west of the Appalachian Mountains. The ship made its maiden voyage on the Mississippi River in 1812, traveling from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to New Orleans, Louisiana. During the nineteenth century, the steamboat would become the preeminent form of commercial and passenger transportation on the nation’s great rivers such as the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the Hudson. Trade flourished; western products were shipped downriver, while European and eastern products like sugar and coffee were carried upriver.

Steam power did not just revolutionize river transportation, but coastal transportation as well. By 1860 the number of steamships operating in Atlantic trade had grown exponentially. While an increase in foreign trade accounts for some of this increase, a large part of this growth was due to the technical improvements of ships. One of these improvements was the use of iron for the ship’s hull. The strength of the iron made steamships more durable and less likely to need frequent repair.

As steam power increased in popularity, sloops and schooners needed to be able to compete with steamships which could carry larger cargo and passenger loads and were not subject to wind conditions. As steamboats became faster, safer, and larger, shipbuilders modified the sloop’s design to make the vessels competitive with steamships. However, some passengers still preferred sailing vessels due to the dangers of boiler explosions on steamships. Thus, steamships led to the decline of sailing vessels. As for Robert Fulton, he would continue his career in canal and shipbuilding, serving on the 1812 commission that recommended the building of the Eire Canal.

The Erie Canal

Proposed in 1808, the Erie Canal proved to be a vital shipping route from Albany to Buffalo, and opened up the land west of the Appalachian Mountains to settlers. The idea of the canal was proposed as early at the mid-eighteenth century. Its purpose was two-fold: to enable settlers easy access across the Appalachians and to provide a trade route across the mountains. The year 1817 saw the beginning of the canal’s construction. When the canal was opened in 1825, shipping traffic on the Hudson River ballooned as a result.

The canal connected Lake Erie with the Hudson River, enabling cargo to travel efficiently between Ohio and New York City. Additionally, the Erie Canal provided settlers an easy route to the West, many of them migrating to western New York, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The success of the Erie Canal started a canal-building boom during the late 1820s and 1830s. Canals were advantageous because they reduced shipping costs significantly: costs dropped from approximately thirty cents a ton per mile in 1820, to two or three cents a ton per mile in 1830. The opening of canals and the canal system had the immediate effect of stimulating the economic growth of previously underserved or unreachable land-locked areas. But when an economic depression hit in the late 1830s, plans to build new, costly canals were scrapped. It was at this time when the railroad was primed to come of age.

Railroads Replace Steamships

The introduction of the steamboat had reduced the cost and time of cargo shipments and made upriver traffic easier. At the time, the steamboat was hailed as an impetus to western expansion. But while river transportation had improved greatly, it still could not compete with the expanse and speed of the railroad system. Though not depicted in Storm King, the railroad and steam-powered locomotive had arguably had the greatest impact on both transportation and western expansion.

Railroads had the distinct ability to connect small, isolated farm towns to much larger national and international markets, a capability that had been lacking from prior modes of water and land transportation. The railroad also opened up parts of the South, most notably Florida, to greater economic development and settlement. The railroad had major advantages over previous modes of transportation, being both flexible and dependable; they were not subject to winter ice as canals were, and were faster and more reliable than steamships. This was especially important when transporting agricultural products. By 1840, more than three thousand miles of railroad track had been laid, predominately in the northeastern region of the country.

In 1851 the American Railroad Journal declared that the railroad had become, “the great agent of civilization and progress, the most powerful instrument for good the world has yet reached.” By 1860 the United States had more railroad track than the rest of the world combined: over thirty thousand miles. Yet, the amount of track was disproportionately split between the North and South, with more track in the North. This factor led to a decisive tactical advantage for the North during the Civil War, further explained in the section War and Technology.

Industry and the Environment

Storm King on the Hudson depicts the worlds of man and nature colliding. The painting depicts a typical day along the heavily trafficked Hudson River in New York State. The idyllic Storm King Mountain provides a scenic background for the steamboats, sailing ships, and rowboats that populate the river. While beautiful, the scene carries a message about the environmental impact of man on the natural world. It was during the time Samuel Colman painted Storm King in 1866 that issues such as preservation and development began to arise, though they did not fully gain traction until the 1880s.

Colman gave “equal time” to both sides of the discussion by dividing his paintings neatly in half. An 1866 review in New York magazine stated that the painting of Storm King on the Hudson, “marks the moment when paradise was invaded by men of commerce… Painters were left with a problem: what to do about the tanning factories, sawmills, paper factories, and the other small businesses that started to overtake the epic waterfalls and elegant forests along the Hudson.”

In the seventeenth century, ships on the Hudson carried fur pelts from upstate New York and Canada to New Amsterdam where they could be shipped overseas to Europe. Early northbound traffic on the river carried mostly manufactured goods, rum, fabric, and other supplies that could not be obtained in the Hudson Valley. Timber from the Adirondack region was also a major cargo on the river, and sawmills operated along the river at Newburgh, Albany, Poughkeepsie, and other towns.

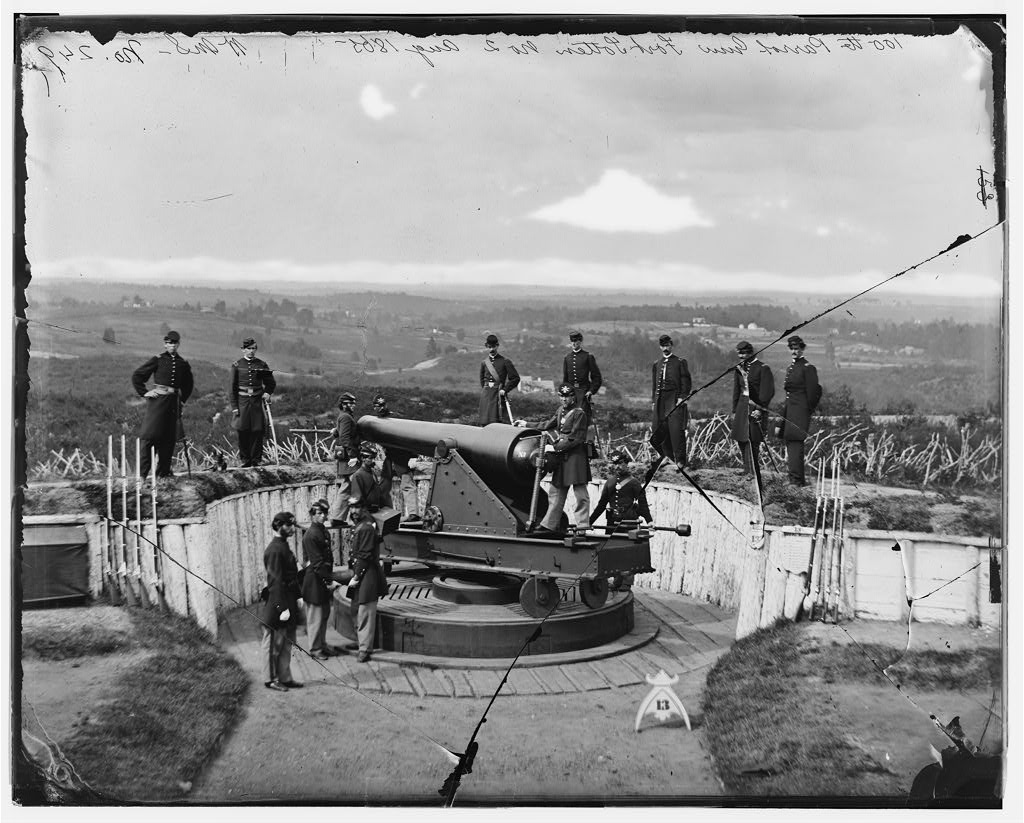

But by the mid-1800’s, the banks of the Hudson River had given rise to several industries served by river vessels, most importantly the iron foundries. The opening of the Erie, Champlain, and Delaware-and-Hudson Canals in the 1820’s made it possible to ship iron ore and fuel (later timber and coal) from further upstate and Pennsylvania by sloop and barge to these foundries. Finished products could then be transported down the Hudson to New York City or back up the canals to the Great Lakes and Canada. There were smelting furnaces at Peekskill and Poughkeepsie, and foundries at Hudson, Kingston, Newburgh, Troy. Cold Spring (not far from Storm King Mountain) was at one point the largest iron foundry in the United States. After the War of 1812, the federal government subsidized the establishment of the West Point Foundry at Cold Spring, near the military academy at West Point. The foundry produced a long-range cast iron cannon, whose effectiveness foundry superintendent Robert Parrott tested by shooting it across the river at Storm King and Crow’s Nest Mountains. This cannon later came to be known as the Parrott cannon. During the Civil War, the foundry employed 1400 workers and played a major role in the Union’s military success. The West Point Foundry also made parts for steamboats, locomotive engines for railroads, iron pipes for city water systems and cotton presses for the textile industry. Burden Iron Works at Troy, New York manufactured cast iron stoves and perfected a mechanized process for making horseshoes, while Uri Gilbert and Son company made gun carriages for the federal government. The federal government commissioned from Albany and Renssaelaer Iron Works in 1861 the navy’s first ironclad vessel, the Monitor, which served the Union in the Civil War.

Iron was not the only natural resource found the in the area; sawmills were incredibly prevalent in the area. In 1833, thirty-three sawmills operated in the town of Moriah, New York alone. Not only were hardwoods cut down for lumber, but they were also used to make charcoal to supply the forges and blast furnaces that processed the iron ore. In The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York, you can see that most of the trees on the lakeshore and on the cliff in are very small. One tree in the middle ground on the left side of the painting leans towards the water, as if uprooted. The area surrounding the lake was once populated by hardwood forests, but those were mostly depleted by the time Martin painted this work. By the mid-nineteenth century, when the hardwoods became depleted and transport of freight in and out of Port Henry improved with the canal and railroad, many of the furnaces converted to coal.

Storm King and the Modern-Day Environmental Movement

In the late twentieth century, Storm King Mountain became a media symbol of a burgeoning environmental movement. From 1963-1980, Storm King became the focus of a controversy that was to have a profound impact on environmental protection. In 1962, the Consolidated Edison (Con Ed) power company submitted a plan for a hydroelectric power plant to be built into the side of Storm King Mountain, facing the Hudson River. The facility was designed to hold a large amount of water in storage for generating power through hydroelectric turbines. Since New York City’s power needs were growing rapidly, Con Ed wanted a back-up power supply in times of peak usage. The environmental organization Scenic Hudson was organized to protest the proposed plant and testify at Federal Power Commission (FPC) Hearings. When the FPC initially granted Con Ed a license in 1965 for the Storm King plant, Scenic Hudson decided to appeal the FPC’s decision, and won an important victory in the appeals court on December 29, 1965. The case drew attention nationwide and the image of the mountain graced the pages of such magazines as Life Magazine. The fight between Scenic Hudson and Con Ed continued until 1980, when the power company abandoned the project and donated the Storm King property to the Palisades and town of Cornwall as parkland.

The Storm King case was a turning point in United States environmental history for several reasons. It created a precedent by which a citizens’ organization could sue a government agency in court. It led to the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires an environmental review of all federally-approved projects. When Congress passed the Clean War Act in 1972 and committed the federal government to clean up polluted waters, the citizen’s suit provision modeled upon Scenic Hudson’s Storm King suit allowed citizen groups to sue polluters under the Act. The Clearwater organization filed the first suit under the Clean Water Act, against the Tuck Tape Company of Beacon, N.Y., which had been dumping titanium dioxide and solvents into Fishkill Creek, a tributary of the Hudson.

Those opposed to the development of Storm King Mountain turned to the paintings of the Hudson River School artists as a profound reason to preserve the landscape of the Hudson Highlands. In 1972, the Scenic Hudson published The Hudson River and Its Painters, which aimed to re-introduce Americans to the masterworks of the Hudson River School and raise money and awareness for the area’s preservation. Art historian Vincent Scully eloquently testified before the FPC in 1966, demanding that the mountain be left alone:

It is not picturesque in the softer sense of the word, but awesome, a primitive embodiment of the energies of the earth. It makes the character of a wild nature physically visible in monumental form. As such it strongly reminds me of some of the natural formations which mark sacred sites in Greece and signal the presences of the Gods; it preserves and embodies the most savage and untrammeled characteristics of the wild at the very threshold of New York.

Scully exalted Storm King in words, just as Samuel Colman had done with pigment and canvas exactly one century earlier when he created Storm King on the Hudson.

Primary Source Connections

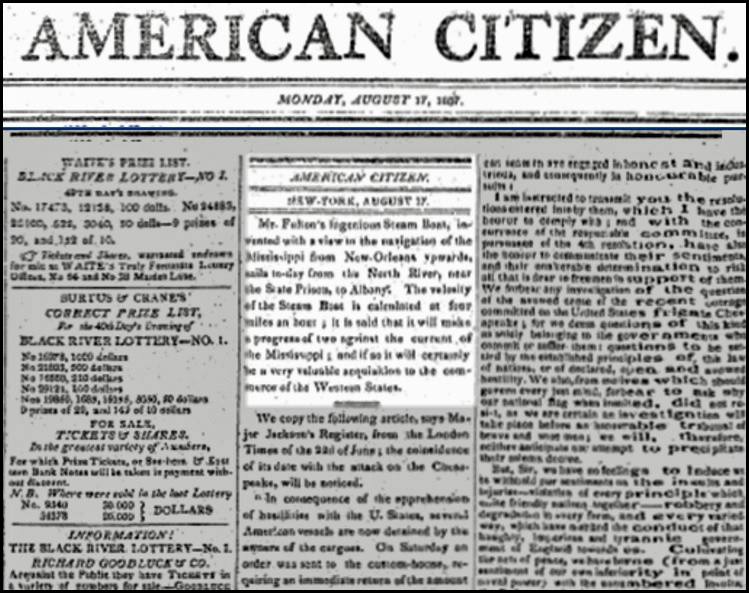

“Mr. Fulton’s ingenious Steam Boat,” in the American Citizen newspaper, August 17 , 1807

“Mr. Fulton’s ingenious Steam Boat,” in the American Citizen newspaper, August 17 , 1807

“Mr. Fulton’s ingenious Steam Boat, invented with a view to the navigation of the Mississippi from New-Orleans upwards, sails to-day from the North River, near the State Prison, to Albany. The velosity [sic] of the Steam Boat is calculated at four miles a hour; it is said that it will make a progress of two against the current of the Mississippi; and if so it will certainly be a very valuable acquisition to the commerce of the Western States.”

Image courtesy of the New York State Library

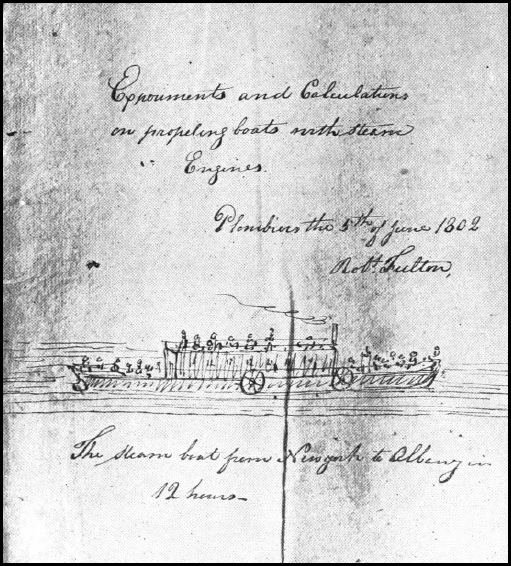

Robert Fulton’s Patent for the Steamboat, February 11, 1809

Robert Fulton’s Patent for the Steamboat, February 11, 1809

The United States Patent Office’s Index of Patents states that on February 11, 1811, a patent was issued to Robert Fulton, however, physical records of this patent do not exist as the records of this and other early patents were destroyed in the Patent Office fire of 1836. The Patent Office building, which did not fully burn down, is today home to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. This drawing is on the title page of the inventor’s notebook, “Experiments and calculations on propeling boats with Steam Engines.” The drawing remained unpublished until included in a 1909 book by Alice Crary Sutcliffe.

Robert Fulton letter to the Editor of the American Citizen newspaper, August 20, 1807

Robert Fulton letter to the Editor of the American Citizen newspaper, August 20, 1807

The Clermont was the brainchild of inventor Robert Fulton and is widely regarded as the first vessel to demonstrate the viability of steam propulsion. Known in its heyday as the North River Steamboat, the vessel was constructed in the winter of 1806 and launched in the spring of 1807. It made its inaugural voyage upriver from New York City, a 150 mile journey. Even with the wind against it, the steamship made the trip in an unprecedented 30 hours. In a letter to the editor of the American Citizen, Fulton expresses his hope that with the proven success of steam transportation, the technology may have greater applicability:

As the success of my experiment gives me great hope that such boats may be rendered of much importance to my country, to prevent erroneous opinions, and give some satisfaction to the friends of useful improvements, you will have the goodness to publish the following statement of facts:

I left New-York on Monday at 1 o’clock, and arrived at Clermont, the seat of Chancellor Livingston, at 1 o’clock on Tuesday, time 24 hours, distance 110 miles; on Wednesday I departed from the Chancellor’s at 9 in the morning, and arrived at Albany at 5 in the afternoon, distance 40 miles, time 3 hours; the sum of this is 150 miles in 32 hours, equal near 5 miles an hour. On Thursday, at 9 o’clock in the morning, I left Albany, and arrived at the Chancellor’s at 6 in the evening; I started from thence at 7, and arrived at New-York on Friday at 4 in the afternoon; time 30 hours, space run through 150 miles, equals 5 miles an hour. Throughout the whole way my going and returning the wind was ahead; no advantage could be drawn from my sails – the whole has, therefore, been performed by the power of the steam engine.

Literary Connections

Life on the Mississippi, 1883, Mark Twain

Life on the Mississippi, 1883, Mark Twain

Life on the Mississippi is Twain’s memoir about his early life as a steamboat pilot’s apprentice on the Mississippi River. These early life experiences on the mighty river would inform many of his best known works, including The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventure of Tom Sawyer. The memoir provides a glimpse into a slice of the American experience.

Moby Dick, 1851, Herman Melville

Moby Dick, 1851, Herman Melville

Major characters in Moby Dick are equated with industrial elements contemporaneous to the period. For instance, in explaining his quest to hunt the elusive whale Moby Dick, Captain Ahab proclaims to his crew, “The path to my fixed purpose is laid with iron rails, whereon my soul is grooved to run. Over unsounded gorges, through the rifled hearts of mountains, under torrents’ beds, unerringly I rush! Naught’s an obstacle, naught’s an angle to the iron way!” Ahab uses words one might use to describe a railroad and a locomotive. In another example, narrator Ishmael likens the strength and power of the ship’s harpooner, Daggo, to “the American army and military and merchant navies, and the engineering forces employed in the construction of the American Canals and Railroads.”

Read it at the Library of Congress

American Notes, 1842, Charles Dickens

American Notes, 1842, Charles Dickens

American Notes provides a contemporary example of a response to the steamboat. While visiting America, English author Charles Dickens rode three different steamboats down the Ohio River and up to St. Louis and back again. He writes of when he first saw a steamboat, “these western vessels are still more foreign to all the ideas we are accustomed to entertain of boats. I hardly know what to liken them to, or how to describe them.”

Across the Plains: With Other Memories and Essays, 1892, Robert Louis Stevenson

Across the Plains: With Other Memories and Essays, 1892, Robert Louis Stevenson

Plains is Stevenson’s memoir as an immigrant traveling from New York City to San Francisco on the transcontinental railroad.

“When I think how the railroad has been pushed through this unwatered wilderness and haunt of savage tribes and now will bear an emigrant for some twelve pounds from the Atlantic to the Golden Gates; how at each stage of the construction roaring, impromptu cities, full of gold and lust and death, sprang up and then died away again . . . and then when I go on to remember that all this epical turmoil was conducted by gentlemen in frock coats with a view to nothing more than a fortune and a subsequent trip to Paris, it seems to me, I own, as if this railway were the one typical achievement of the age in which we live, as if brought together into one plot all the ends of the world and all the degrees of social rank, and offered to some great writer the busiest, the most extended, and the most varied subject for an enduring literary work.”

“To a Locomotive in Winter”, 1876, Walt Whitman, in Leaves of Grass (various editions published 1855 through 1892)

“To a Locomotive in Winter”, 1876, Walt Whitman, in Leaves of Grass (various editions published 1855 through 1892)

The locomotive was the quintessential emblem of American technological progress in the late 1800’s. Whitman, like many of his contemporaries, associated the locomotive, and consequently the railroad, with progress and modernity as evidenced by this poem.

Artwork Connections

[Pennsylvania Railroad Locomotive at Altoona Repair Facility], ca. 1868, Unidentified Artist

Dale Creek Bridge, ca. 1885, Charles Roscoe Savage

Media

Podcast: The Civil War and American Art (2 min)

In this podcast, curator Eleanor Jones Harvey discusses 6 featured paintings from “The Civil War and American Art” exhibition. This episode looks at “The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York” by Homer Dodge Martin.

The Industrial Economy: Crash Course US History – PBS (12 min) TV-G

This PBS video teaches you about the Industrial Economy that arose in the United States after the Civil War. After the Civil War, many of the changes in technology and ideas gave rise to this new industrialism.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

“Approaching Research: The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

Subject: History

America on the Move – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

An online exhibition on the transportation revolution.

The Unbelievable Success of the American Steamship – Smithsonian Magazine

This article explores how “Fulton’s Folly” transformed the nation’s landscape.

Glossary

Antietam (Battle of): September 16, 1862 near Sharpsburg, Maryland, considered the bloodiest single-day battle in American history; the combined Union and Confederate casualties numbering 22,717 persons.

Benjamin West: (1738-1820) American painter who became court painter to King George III and was president of the Royal Academy in London, where he became a mentor to many American painters.

broad gauge: railways that use a track wider (usually 5 ft.) than the standard gauge of 4ft. 8.5 in.

gauge: the distance between the inner edges of the heads of the rails in a track.

Grant (Ulysses S.): (1822-1885) 18th President of the United States and commanding general of the Union Army during the Civil War.

gun carriages: wheeled devices that carried heavy iron cannons to and from the battlefields.

hull: the watertight body of a ship or boat.

interior lines: the military circumstance of either being able to move over a shorter distance to execute maneuvers and effect reinforcements or possessing a more efficient transportation method, such as a railroad, that allows for rapid deployments.

Louisiana Purchase: (1803) purchased from France during President Thomas Jefferson’s administration, the region of the United States encompassing land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains.

March to the Sea: military campaign waged in 1864 by General William Tecumseh Sherman which began with the capture of Atlanta and ended with the capture of the port city of Savannah. It is renowned for its bold path deep into enemy territory without the use of traditional supply lines and its level of destruction on the South. Also known as the Savannah campaign.

New Amsterdam: the 17th century Dutch settlement at the southern-most tip of the island of Manhattan in current-day New York City.

Parrott cannon: (also known as the Parrott rifled gun) Invented in 1860 by Captain Robert Parrott, a front-loading artillery weapon. Parrott perfected the weapon by reinforcing the breech (rear-end) of the cast iron tube with an iron band. The term “rifle” refers to the grooves inside the barrel of the cannon, which imparted a spin to the projectile. The cannon was later patented in 1861.

Robert Fulton: (1765-1815) American engineer and inventor, credited with inventing the first commercially successful steamship.

Robert Livingston: (1746-1813) New York politician, lawyer, and diplomat who financed Robert Fulton’s steamship project.

Robert Parrott: (1804-1877) American soldier and inventor of military artillery. Best known for the eponymous Parrott cannon. After resigning his commission from the military, he became superintendent of the West Point Foundry Ironworks in Cold Spring, New York, where he invented the eponymous Parrott cannon.

Savannah campaign: military campaign waged in 1864 by General William Tecumseh Sherman which began with the capture of Atlanta and ended with the capture of the port city of Savannah. It is renowned for its bold path deep into enemy territory without the use of traditional supply lines and its level of destruction on the South. Also known as the March to the Sea.

schooner: a sailing vessel with two or more masts.

Sherman’s neckties: a railway destruction tactic developed by General William Tecumseh Sherman in which rails were heated and twisted into loops resembling neckties, a tactic which rendered them unusable.

sloop: a small sailing vessel with one mast.

standard gauge: a railway track that is 4ft. 8.5 in. wide.

Transportation Revolution: a period in the U.S. when transportation became cheaper and more efficient with the rapid development of new technology. Many canals, roads, and railroads were built at this time.

William Tecumseh Sherman: (1820-1891) Union army general during the Civil War, best known for his victory at the Battle of Shiloh, the capturing of Atlanta, and his March to the Sea.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 6 – The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

- Standard 1A – The student understands the connections among industrialization, the advent of the modern corporation, and material well-being.

- 9-12 – Examine how industrialization made consumer goods more available, increased the standard of living for most Americans, and redistributed wealth.

- Standard 1D –The student understands the effects of rapid industrialization on the environment and the emergence of the first conservation movement.

- 7-12 – Explain how rapid industrialization, extractive mining techniques, and the “gridiron” pattern of urban growth affected the scenic beauty and health of city and countryside.

![[Pennsylvania Railroad Locomotive at Altoona Repair Facility]_1994.91.213_1a](https://americanexperience.si.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Pennsylvania-Railroad-Locomotive-at-Altoona-Repair-Facility_1994.91.213_1a-300x184.jpg)