Capture of the H.B.M. Frigate Macedonian by U.S. Frigate

United States, October 25, 1812, 1852, Thomas Chambers

Often referred to as the “forgotten war,” the War of 1812 is often overshadowed by its famous predecessor, the American Revolution, but it is just as important to the history of this country. It was this war that actually tied up many of loose ends leftover from the American Revolution. Naval battles and territorial disputes with the British and their Native American allies took precedence during this military conflict. These artworks, both created years after the events they depict, represent two significant events that benefited the United States; the capture of the British frigate Macedonian and the death of the Shawnee Indian chief Tecumseh. The capture of the Macedonian was a significant victory for the United States as it was the first British ship to be captured in the war. Tecumseh, angered by U.S. expansion, led a multi-tribal army which allied itself with the British against the United States. Yet with Tecumseh’s death at the Battle of the Thames near our Canadian border, the Indian alliance fell apart and forced a British retreat which effectively ended the War of 1812. These two artworks look back nostalgically on the events that helped to secure the status of the young nation as powerful occupant on the world stage.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

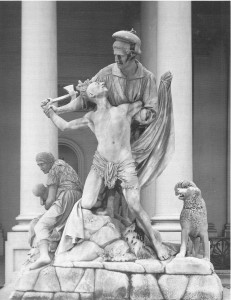

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What information can we learn about Tecumseh, his death, and the way he is remembered in this sculpture? What clues does Pettrich give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Who was Tecumseh? What do his clothing and weapons tell us about him?

The figure’s muscular form, along with the larger-than-life size of this sculpture, communicate a sense of strength, both in body and character. Tecumseh holds a long-handled tomahawk, which he grasps in order to hold the upper half of his body upright. Feathers decorate the edges of his pants and the sheath of his knife, which he holds in his left hand. Together these details, along with his headdress and arm band, identify him as a powerful Native American leader.

The figure’s muscular form, along with the larger-than-life size of this sculpture, communicate a sense of strength, both in body and character. Tecumseh holds a long-handled tomahawk, which he grasps in order to hold the upper half of his body upright. Feathers decorate the edges of his pants and the sheath of his knife, which he holds in his left hand. Together these details, along with his headdress and arm band, identify him as a powerful Native American leader.

What has happened to Tecumseh?

As the title of the artwork imparts, the great Indian leader is dying, having been mortally wounded in battle. He slumps against a broken tree stump, using his long-handled tomahawk for support as he sinks to the ground. How would you describe Tecumseh’s facial expression? Does he appear to be pained, panicked, resigned, or sorrowful? Is this a man who is scared to face death or does appear accepting of his fate?

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Tecumseh was a general of the Shawnee Indian nation who resisted the advance of American westward expansion and fought on the side of the British during the War of 1812. He was known as a powerful, charismatic leader who was able to unite varied Native American tribes against the ever-encroaching settlement of the United States.

The artist created this artwork nearly fifty years after Tecumseh’s death. Though Pettrich had observed North American Indians delegations that had traveled to Washington, D.C. in the 1820s and 1830s, he did not directly base Tecumseh’s clothing and accoutrements on specific Shawnee artifacts. His main objective was capturing the essence of a great, conquered warrior. This sculpture was created while the artist was living in Brazil and so the amalgamation of garments and weapons Pettrich chose were taken from engravings he had made while he was living in America, rather than from direct observation of Shawnee artifacts.

The artist modeled Tecumseh’s pose on another famous statue called The Dying Gaul, an ancient Roman copy of a lost Greek marble. Like The Dying Gaul, Tecumseh has been fatally wounded but reclines gracefully, with his limbs extended elegantly. Both statues depict men who have lost their battles and are close to death but remain serene and dignified, resigned to their fate. Both statues emphasize the strength of the individual dying figure, and represent the ultimate fates of their respective nation/tribe.

By the time Pettrich created this sculpture of Tecumseh, the Indian leader had become somewhat of an American folk hero in the eyes of white America, despite the fact that he had fought against the American army. The American imagination was captured by this man, who was admired as a great warrior and a charismatic leader. He typified the nineteenth century’s idea of the “noble savage,” an idealized representation of a person outside of “civilization.” Praise for vanquished foes – once safely out of the way – was a longstanding heroic tradition. This artwork served to glorify an American victory by men like future U.S. president William Henry Harrison, whose forces had defeated Tecumseh.

Harrison, among many others, took credit for Tecumseh’s death, though no one knows for sure who ended Tecumseh’s life. What is known is that his last stand took place at the Battle of the Thames, where five days of intense fighting led to a deadly standoff between the Americans and a combined Indian/British force. Some accounts suggest that after his death, Tecumseh’s body was disfigured by American soldiers who took strips of his skin as trophies. Rather than depicting the horror of battle and death, Pettrich presents a sanitized and romantic vision of Tecumseh’s final moments. He is thoroughly defeated, yet his nobility is preserved until the very end. Tecumseh’s death sounded the death knell for the intertribal resistance Tecumseh had created in order to end the encroachment of white American settlement on Indian lands.

Historical Background

Causes of the War of 1812

In order to fully understand the importance of the American naval victory occurring in this painting, we must first understand exactly why the United States went to war against Great Britain in 1812. It was not one, but a series of factors that ultimately led to the decision to take up arms against the greatest naval power of the day. An important, often overlooked, factor that led to the War of 1812 was the Louisiana Purchase. The United States wanted the large swath of land for westward expansion and exploration; France urgently needed money to pay for soldiers and supplies in its coming war with Great Britain. After some negotiating, the United States paid $15 million for the territory. Shortly thereafter, Napoleon declared war on Great Britain, and the resulting series of conflicts, collectively called the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), wreaked havoc on the French and English economies. As European rural economies slowed, the United States became a major supplier of commodities to Britain and France, both of whom urged the young country to remain neutral during the conflict.

In addition to exporting their own goods, American ships also re-exported goods from the Caribbean colonies of France and Britain back to Europe. At first American suppliers made huge profits, but as the war grew to a stalemate, with Napoleon occupying mainland Europe and the British controlling the seas, the warring countries soon began to interfere with the American re-export trade. Angered by this trade, Britain decided to try and starve the French in to submission by blockading French ports and consequently all American ships bound for France. They reasoned this course of action with the resurrected Rule of 1756, which declared that if neutral countries transported goods from an enemy colony to the continent, it would be seen as an act of war. The rule also decreed that neutral nations in wartime could only carry items that had been transported in times of peace; effectively banning re-export trade. In the eyes of Great Britain, this rule legitimized the seizure of American ships. While both countries seized American ships to stymie the other, British seizures were seen as a much more grievous act as they took place off American shores, while French seizures took place in and near French-controlled European ports.

Angered at Britain for violating neutral trade rights, the United States Congress passed the Non-Importation Act of 1806 which barred the importation of British goods that could be made in America or could be purchased through any other country. Britain responded by using its navy to further block French-controlled European ports. France replied by outlawing trade with Britain. Various decrees were soon volleyed back and forth. If the U.S. complied with one country’s regulations, it became a target of the other.

Further angering Americans, the British Royal Navy also took part in impressment, a practice that forced captured American sailors into service for the Royal Navy. Britain initially practiced impressment to look for deserters of the Royal Navy who had joined American merchant ships for better pay, food, and conditions. Yet soon, impressing American- born sailors became common practice; an estimated 6,000 American sailors were impressed before the United States declared war in 1812. Britain’s practice of impressing Americans grew as their war with France intensified, and the need for more sailors became paramount. Efforts by the United States to remain neutral in the face of these factors fell flat. In his message to Congress, dated June 1, 1812, President James Madison stated that, “the conduct of [Britain’s] Government presents a series of acts hostile to the United States as an independent and neutral nation.” He outlined three important validations for going to war. The first was on the subject of neutral rights: “Our commerce has been plundered in every sea, the great staples of our country have been cut off from their legitimate markets, and a destructive blow aimed at our agricultural and maritime interests.” The second dealt with the issue of British impressment:

The practice, hence, is so far from affecting British subjects alone that, under the pretext of searching for these, thousands of American citizens, under the safeguard of public law and of their national flag, have been torn from their country and from everything dear to them; have been dragged on board ships of war of a foreign nation and exposed, under the severities of their discipline, to be exiled to the most distant and deadly climes, to risk their lives in the battles of their oppressors, and to be the melancholy instruments of taking away those of their own brethren.

The third justification concerned the association between the British and the American Indians: “It is difficult to account for the activity and combinations which have for some time been developing themselves among tribes in constant intercourse with British traders and garrisons without connecting their hostility with that influence and without recollecting the authenticated examples of such interpositions heretofore furnished by the officers and agents of that Government.” Following this defense, President Madison made a final push for war:

Our moderation and conciliation have had no other effect than to encourage perseverance and to enlarge pretensions. . . .Whether the United States shall continue passive under these progressive usurpations and these accumulating wrongs, or, opposing force to force in defense of their national rights, shall commit a just cause into the hands of the Almighty Disposer of Events . . . is a solemn question which the Constitution wisely confides to the legislative department of the Government. In recommending it to their early deliberations I am happy in the assurance that the decision will be worthy the enlightened and patriotic councils of a virtuous, a free, and a powerful nation.

Going to war with Britain was required if the United States was to maintain its sovereignty and its maritime rights.

Congress agreed with President Madison and declared war on June 18, 1812, but the vote was far from unanimous. Representatives from the Western and Southern states, the primary beneficiaries of a victory over Britain, were in favor. The Northeastern states were opposed, as they had the most to lose with their commercial rights and businesses at stake. Despite the justification President Madison provided for going to war, many Americans believed that the real motives were less than noble. Some thought that war was declared because of America’s wounded pride and loss of honor because of the successive British impressments and rights violations. Others suspected, and correctly so, that the war was solely an opportunity for the United States to expand its borders and attain sought-after territory in the Northwest (Canada) and in the South (present-day Florida,) which were occupied by several tribes of Indians and controlled by British and Spanish powers, respectively.

Knowing that confronting an unrivaled naval power like Britain at sea would be unwise, the United States resolved to primarily challenge the British on land by invading British occupied Canada. They reasoned that Canada would be both valuable, for its land, and vulnerable due to its small population and light defense. Additionally, Canada was also the area from which Britain stimulated anti-American aggression and sentiment amongst the American Indians. The Indians resented American settlers for occupying their land, and for competing with them for the supply of wild game, and the Indians’ livelihoods depended on fur trade with Europe. With Britain furnishing the Indians with supplies, it was only a matter of time before Indian leader Tecumseh would come to power and organize a pan-tribal coalition to take on the expanding American empire.

Tecumseh and the War of 1812

The War of 1812 pitted the United States against a combined British-Indian military force. While there were many causes that led up to the war, one central cause was British support for the American Indian opposition over American expansion in the Northwest, land which was still occupied by the Indians. Tecumseh, a skilled Shawnee warrior and charismatic orator, believed that a pan-Indian federation could stop or slow the pace of American westward expansion. He hoped that old tribal rivalries could be set aside so that the unified tribes of the Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley could move as one and resist the United States expansion into Native territory. Tecumseh had tried negotiating face-to-face with the federal governor of the Indiana Territory, William Henry Harrison, on two occasions. Harrison, after interacting with Tecumseh, assessed him as “one of those uncommon geniuses who spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things.” Negotiations between the two fell through and in a preemptive strike, Harrison gathered one thousand men and attacked Tecumseh’s base along the Tippecanoe River. At the time Tecumseh, who was not yet ready to launch a physical assault on the opposition, was recruiting allies for the impending war. His brother Tenskwatawa, known as the Shawnee Prophet, was placed in charge. Tenskwatawa, while greatly respected, was not a warrior like his brother Tecumseh. Even though Tenskwatawa’s forces outnumbered Harrison’s, Harrison and his men were still able to stand their ground and eventually overpower the Indians as they began to run out of ammunition. This operation, now referred to as the Battle of Tippecanoe was, in effect, the first engagement of the War of 1812.

Battle of the Thames, 18??, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago, Library of Congress

Tecumseh’s warriors struck back in retaliation, attacking forts and sending white settlers fleeing back towards the Ohio River. They then joined up with British forces in Canada. After several altercations, the British were in need of supplies and soon retreated up the River Thames. The final stand came near Moraviantown on October 5, 1813. The combined Indian and British forces set up two miles west of Moraviantown on the north side of the River Thames, an area full of swampy thickets. When the American forces realized that the Indians were entrenched in the thickets, Harrison decided to attack the British first, believing that if they retreated it would demoralize the Indians enough to allow the Americans to sweep around their flank. Within five minutes of an infantry attack toward the Indian lines and a mounted militia attack towards the British center, the British retreated in panic, led by their general Henry Proctor, who reportedly galloped past his men in the retreat back towards Moraviantown. This left only Tecumseh’s warriors, who at Tecumseh’s encouragement did not follow the British into a retreat. Intense fighting ensued and mounted American forces drove the Indian lines together; while the horses could not travel as fast into the underbrush towards the Indians, ammunition from American guns could. Sometime during this assault, Tecumseh was shot and killed. Harrison was hailed as a national hero for his actions in battle. His later political career would remind American citizens of these accomplishments; his witty 1840 presidential campaign slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” referenced his days as an Indian fighter during the Battle of Tippecanoe.

Without their charismatic leader Tecumseh, the alliances between the North American tribes quickly dissolved. Many tribes lost their enthusiasm for fighting and later did little to stop the rapid expansion that occurred after the battle. The success of the American forces at the Battle of the Thames effectively re-established American control over the western frontier. This American success in 1813 certainly contributed to the belief held by many Americans at the time that the American Indian was destined for extinction and that westward expansion was destined to continue.

The Portrayal of the American Indian in American Culture

The way in which American Indians were portrayed in art and literature by artists and writers of the nineteenth-century largely reflected how they were perceived in relation to the American idea of Manifest Destiny. The white American population viewed the Indian in one of two ways. In the more sympathetic view, the figure of the American Indian signified the sad and inevitable, yet perceived as necessary, loss of the native population as a result of the white colonization and expansion. Once the Indian no longer posed a threat to the white population, their demise could be lamented and mourned and consequently they would be remembered as ‘noble savages.’ Scholar Renato Rosaldo has coined this viewpoint, “imperialist nostalgia.” Another interpretation of the Indian’s inclusion in art and literature is decidedly less romantic; the inclusion of the Indian was meant to show the percieved natural superiority of the white over the native, essentially communicating the message of white civilization triumphing over Indian “savagery.” During the time sculptor Ferdinand Pettrich was actively working in America, beginning in 1835, this second viewpoint seems to have been largely perpetuated by the United States Government through artistic commissions that reflected policies regarding the American Indian.

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act which authorized him to grant unsettled lands west of the Mississippi River to American Indians in exchange for their land that fell within existing state borders. Many tribes went peacefully, but others like the Cherokees resisted and in 1838 and 1839 they were forcibly removed from their lands. Their march west became known as the Trail of Tears, where as many as 4,000 Cherokees died from starvation and disease. This governmental act was yet another blow to the American Indian population, as it reminded the public of the seemingly necessary push of the Indian population west for the ‘greater good’ of westward expansion.

During the War of 1812, the Capitol was partially burned and destroyed by the British. Reconstruction on the building began in 1815 after the close of the war and lasted well into the 1820’s. In the following two decades, the United States government would commission sculptures to adorn the newly rebuilt Capitol. These highly paid commissions were sought after by artists from around the world, some of which Pettrich competed for but ultimately lost. These Capitol sculptures were, however, not strictly meant for aesthetics but served to push an agenda; they functioned as visual political propaganda to support United States policy regarding the American Indian. It could be argued that these government commissions largely influenced the public and its opinions on American Indians.

Discovery of America, 1837-50, Luigi Persico, Image courtesy of U.S. Capitol Historical Society

Two sculptures that were commissioned by the government in 1837 that support this theory are Italian sculptor Luigi Persico’s Discovery of America and American sculptor Horatio Greenough’s The Rescue. These sculptures once flanked the eastern staircase to the Capitol, but have since been retired to storage. Discovery of America portrays Christopher Columbus in a triumphant pose holding a globe in his outstretched hand. An Indian woman recoils at the sight of him and recedes to the rear of the sculpture. Art historian Vivien Green Fryd’s interpretation of the sculpture is that it is proclaiming “the dominance of the white man over the effeminate and, by implication, weak and vulnerable Indian. As the newcomer advances onto the soil of the New World, the native begins her retreat in the face of his power and superiority.”

The Rescue, 1837-50, Horatio Greenough, Image courtesy of U.S. Capitol Historical Society

In Greenough’s Rescue, a male Indian is shown attacking a white woman and child. He is apprehended by a much larger and stronger white man; “the two figures now form a single unit, suggesting not assimilation but subjugation in the interlocked relation between pioneer and warrior. As in the left staircase group, the explorer dominates, not only because of his towering size and physique but also because of his advantage in strength over the powerless Indian.”

Artists hoping for highly paid government commissions would have had to reflect the government’s policy on American Indians. If their depiction of the Indian did not support policy and/or mainstream views on westward expansion, they would not have received government sponsored commissions. It is for this reason that Pettrich’s sculpture of Tecumseh might not have been purchased by the government if it was viewed as exemplifying the ‘noble savage’ rather than as a representation of the declining Indian population. It might partially explain why the sculpture of Tecumseh was relegated to the depths of the crypt below the Capitol rotunda until it was moved to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1878.

In Pettrich’s The Dying Tecumseh, there is one compositional element in particular which serves to symbolize the decline and eventual death of the Indian race: the cut tree stump on which Tecumseh leans. The juxtaposition of the dying or lamenting Indian with a tree stump was a recognized visual tradition in both American art and literature during the nineteenth-century. In John Augustus Stone’s play Metamora, or the Last of the Wampanoags, the title character laments, “O my people . . . the race of the red man has fallen away like trees of the forest before the axes of the palefaces.” Here, the tree stump highlights the common fate between the Indian population and nature. An 1855 review of the play explicitly connects the tree stump to the fate of the Indian: “His tribe has disappeared, he is left alone, the solitary off-shoot of a mighty race; like the tree-stump beside him he is old and withered, already the axe of the blackwoodsman disturbs his last hours; civilization and Art, and agriculture . . . have desecrated his home. Both nature and the Indian must be overpowered for white civilization’s unimpeded growth.”

Primary Source Connections

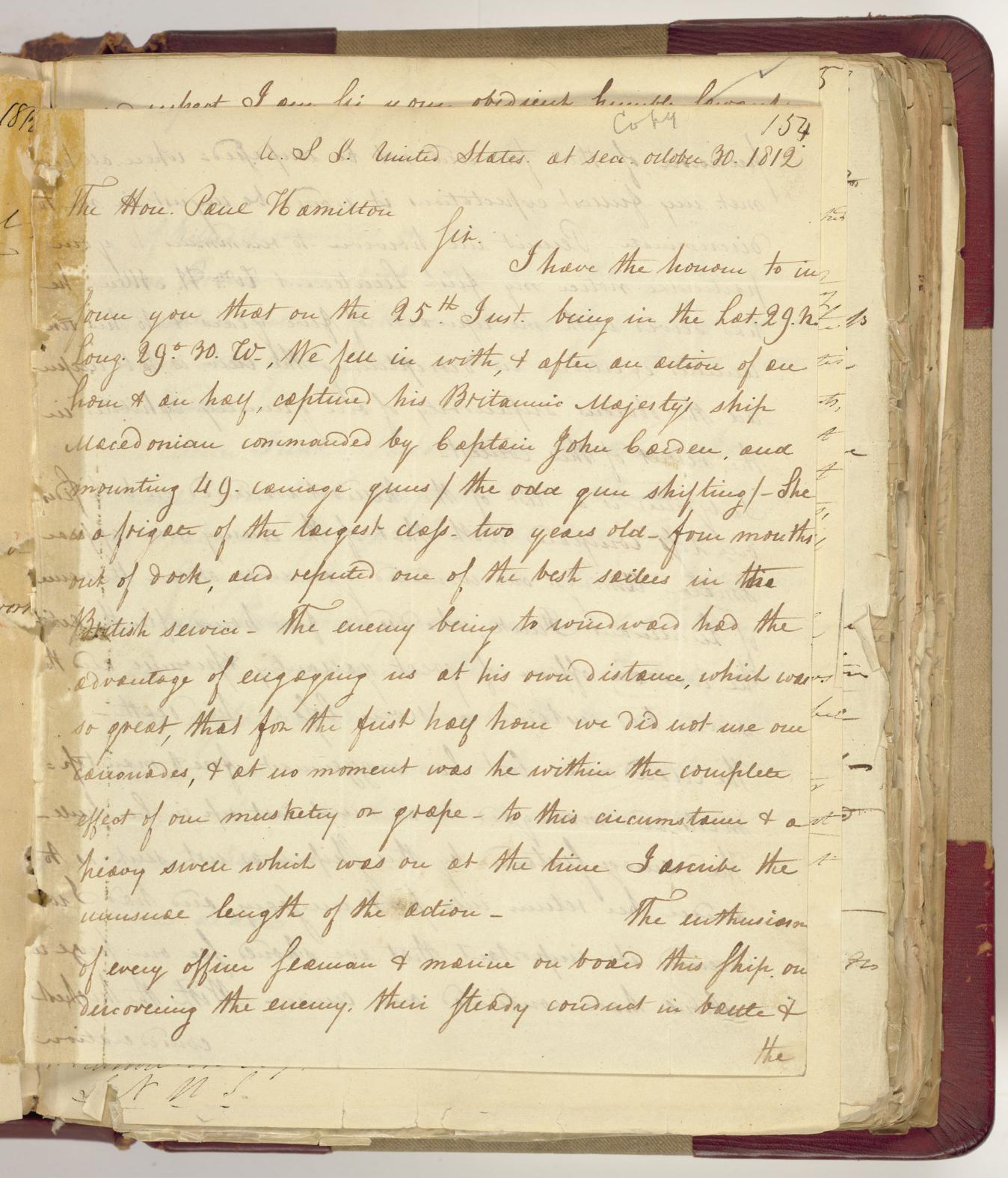

Letter from Commodore Stephen Decatur to Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton Regarding the Capture of H.B.M. Frigate Macedonian by U.S. Frigate United States, October 30, 1812

Letter from Commodore Stephen Decatur to Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton Regarding the Capture of H.B.M. Frigate Macedonian by U.S. Frigate United States, October 30, 1812

Read the document at the National Archives

Writing on October 30, while aboard the USS United States in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of the Azores, Decatur explains to Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton how the United States defeated and captured the frigate HBM Macedonian during a 1-1/2 hour battle five days earlier. Decatur praises the actions of his seamen and marines, listed the names of those men killed or wounded on both ships, and describes the condition of the Macedonian.

Connect it to the Artwork: “Teaching with Documents: Letter by Stephen Decatur and Painting by Thomas Chambers Related to the War of 1812.”

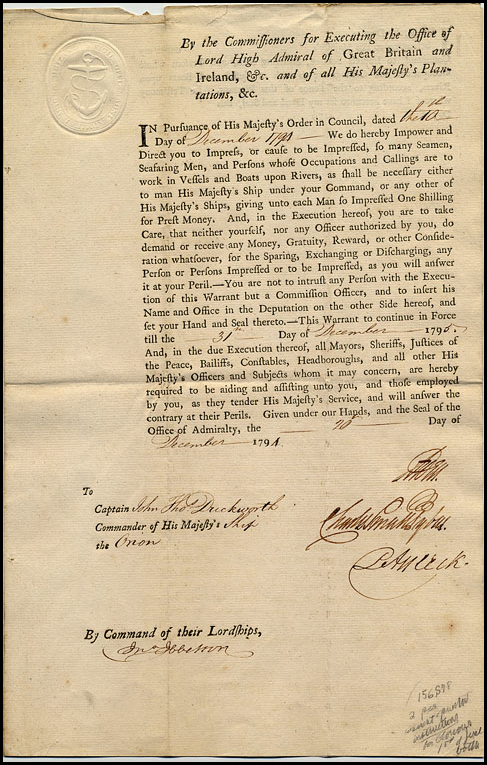

British Admiralty Press Warrant, 1794

British Admiralty Press Warrant, 1794

Read more at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

This British Admiralty document authorized Capt. John Thomas Duckworth of HMS Orion to seize, or impress, as many men as he needed to man his vessel or “any other of His Majesty’s Ships.” Each man recruited this way was to receive one shilling as “Prest Money.” – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Tecumseh’s response to Gov. William Henry Harrison, 1810

Read the Transcription and Download at DigitalHistory.uh.edu

“Told by Governor Harrison to place his faith in the good intentions of the United States, Tecumseh offers a bitter retort. He calls on Native Americans to revitalize their societies so that they can regain life as a unified people and put an end to legalized land grabs.”

Since my residence at Tippecanoe, we have endeavored to leave all distinctions, to destroy village chiefs, by whom all mischiefs are done. It is they who sell the land to the Americans. Brother, this land that was sold, and the goods that was given for it, was only done by a few…. In the future we are prepared to punish those who propose to sell land to the Americans. If you continue to purchase them, it will make war among the different tribes, and at last I do not know what will be the consequences among the white people. Brother, I wish you would take pity on the red people and do as I have requested. If you will not give up the land and do cross the boundary of our present settlement, it will be very hard, and produce great trouble between us.

The way, the only way to stop this evil is for the red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was at first, and should be now–for it was never divided, but belongs to all. No tribe has the right to sell, even to each other, much less to strangers…. Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them for all the use of his children?

Thomas Jefferson’s Instructions to Meriwether Lewis, June 20, 1803

Thomas Jefferson’s Instructions to Meriwether Lewis, June 20, 1803

Read the Transcript or See the Original Document at the Library of Congress

“No document proved more important for the exploration of the American West than the letter of instructions Jefferson prepared for Lewis. Jefferson’s letter became the charter for federal exploration for the remainder of the nineteenth century. The letter combined national aspirations for territorial expansion with scientific discovery. Here Jefferson sketched out a comprehensive and flexible plan for western exploration. That plan created a military exploring party with one key mission—finding the water passage across the continent “for the purposes of commerce”—and many additional objectives, ranging from botany to ethnography.” – Library of Congress

The Treaty of Ghent, 1814

The Treaty of Ghent, 1814

Read it at OurDocuments.gov

In 1814, both American and British delegations were working on terms for peace to end the War of 1812. An agreement was finally reached and signed on December 24, 1814 in Ghent, Belgium. Great Britain agreed to relinquished all conquered territory in the Northwest United States and plans were made to settle the boundary between the United States and Canada.

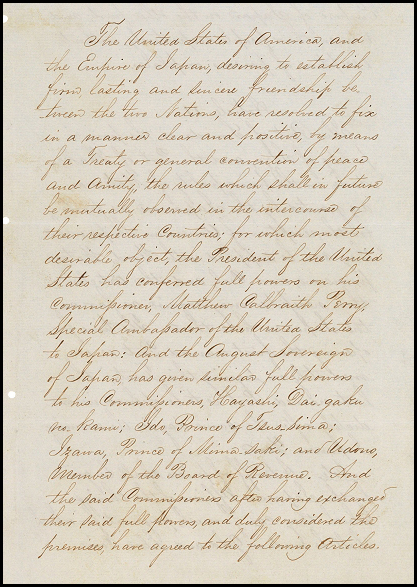

The Treaty of Kanagawa, 1854

The Treaty of Kanagawa, 1854

Read it at Archives.gov

“On March 31, 1854, the first treaty between Japan and the United States was signed. The Treaty was the result of an encounter between an elaborately planned mission to open Japan and an unwavering policy by Japan’s government of forbidding commerce with foreign nations. Two nations regarding each other as “barbarians” found a way to reach agreement.” – National Archives

Literary Connections

Fiction:

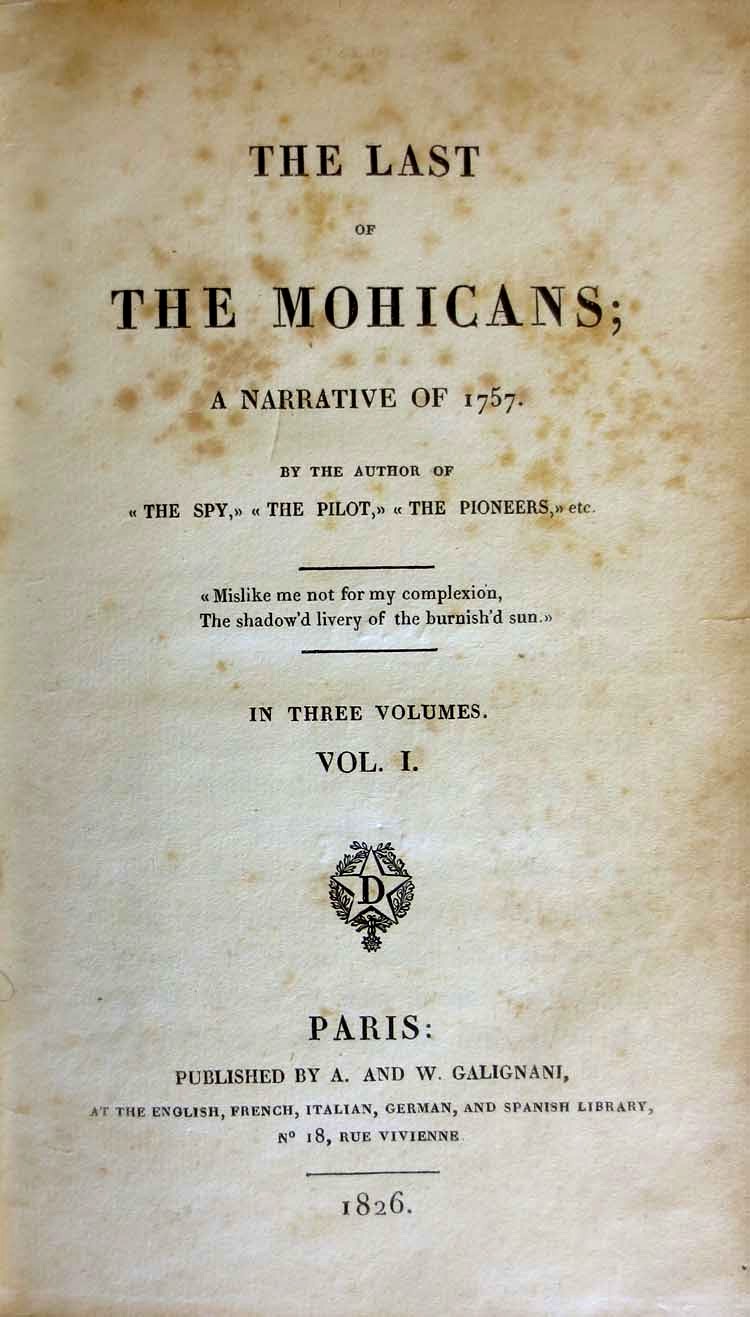

The Last of the Mohicans, 1826, James Fenimore Cooper

The Last of the Mohicans, 1826, James Fenimore Cooper

Read it at Project Gutenberg

“Deep in the forests of upper New York State, the brave woodsman Hawkeye (Natty Bumppo) and his loyal Mohican friends Chingachgook and Uncas become embroiled in the bloody battles of the French and Indian War. The abduction of the beautiful Munro sisters by hostile savages, the treachery of the renegade brave Magua, the ambush of innocent settlers, and the thrilling events that lead to the final tragic confrontation between rival war parties create an unforgettable, spine-tingling picture of life on the frontier. And as the idyllic wilderness gives way to the forces of civilization, the novel presents a moving portrayal of a vanishing race and the end of its way of life in the great American forests.” – Goodreads.com

Poetry:

“A Walk at Sunset” 1855, William Cullen Bryant

“A Walk at Sunset” 1855, William Cullen Bryant

Read it at PoemHunter.com

A romanticized poem on nature, the journey of life, and the Indian civilization in America. The poem reveals Bryant’s interest in the influence of the American Indian past on the identity of white America. He introduces the idea that civilizations rise and fall, much like the sun, alluding the inevitable fate of American Indian culture. (Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery)

Play:

Metamora, or the Last of the Wampanoags, 1829, John Augustus Stone

Metamora, or the Last of the Wampanoags, 1829, John Augustus Stone

Find it in a Library

The play follows the title character Metamora, a heroic and noble American Indian chief, and his tragic fall at the hand of English settlers in seventeenth century New England. The 1860 photograph by Matthew Brady at left, shows popular 19th-century actor Edwin Forrest dressed as the character Metamora. (Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery)

Artwork Connections

The Signing of the Treaty of Ghent, Christmas Eve, 1814, 1914, Sir Amedee Forestier

The Treaty of Ghent was signed by representatives of Great Britain and the United States, formally ending the War of 1812. The terms of the treaty were that all conquered territory was to be returned and a permanent border between the United States and Canada was to be established. In this artwork, British delegate Baron James Gambier (left) shakes hands with then-diplomat and future president John Quincy Adams (right).

William Henry Harrison, 1808-1897, John Sartain, Copy after James Reid Lambdin

William Henry Harrison, 1808-1897, John Sartain, Copy after James Reid Lambdin

Before becoming the ninth President of the United States, Harrison won national fame as a general in the War of 1812, particularly his military leadership during the Battle of the Thames which with the death of Indian Confederation leader Tecumseh, effectively ended the war.

Self Portrait, 1840, Ferdinand Pettrich

Self Portrait, 1840, Ferdinand Pettrich

Pettrich modeled this portrait around the time that he executed what has become his best-known statue, that of General George Washington in the act of resigning his commission as commander of the army. Confident from the success of that monumental work, he represented himself in his professional garb as a skilled sculptor.

Media

The War of 1812 – Crash Course US History – PBS (13 min) TV-G

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and its former colonial overlord England. The war lasted until 1815, and it resolved very little. The video takes you through the causes of the war, tell you a little bit about the fighting itself, and get into just why the US Army couldn’t manage to make any progress invading Canada.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Subject: Art

“Approaching Research: The Dying Tecumseh” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

The Dying Tecumseh and the Birth of a Legend – Smithsonian Magazine, July 1995, by Bil Gilbert

A sculpture in the Smithsonian collection reveals much about how the Indians of the West were viewed in the early ages of the United States.

Subject: History

The Price of Freedom: War of 1812 – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

America went to war against Great Britain to assert its rights as an independent, sovereign nation, and to attempt the conquest of Canada. The United States achieved few of its goals and the war ended in a stalemate. But the British bombardment of Ft. McHenry inspired Francis Scott Key to write a poem that later became the National Anthem. And Andrew Jackson’s victory over the British in New Orleans gave the country a new hero. This online exhibition provides historical essays paired with primary resources.

A History of the War of 1812 and the Star-Spangled Banner (PDF) – Smithsonian’s History Explorer

Glossary

Battle of the Thames: (October 5, 1813) a military engagement between the United States and the combined forces of the United Kingdom and a multi-Indian tribe coalition, which occurred in present-day Ontario, Canada next to the Thames River. Also referred to as the Battle of Moraviantown.

Battle of Tippecanoe: (November 7, 1811) a military engagement between the United States and Indian warriors fighting for Tecumseh’s Indian coalition, which occurred in modern-day Lafayette, Indiana. This is considered the first engagement in the War of 1812.

Indian Removal Act: (1830) passed by Congress during President Andrew Jackson’s administration, the law authorized the president to grant unsettled lands west of the Mississippi River to American Indians in exchange for their ancestral homelands, which were within the existing borders of the United States.

impressment: the act or policy of seizing persons and compelling them to serve in the military, especially in naval services.

Louisiana Purchase: (1803) purchased from France during President Thomas Jefferson’s administration, the region of the United States encompassing land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains.

Manifest Destiny: the nineteenth-century doctrine or belief that the expansion of the U.S. throughout the American continents was both justified and inevitable.

Metamora, or the Last of the Wampanoags: (1829) written by John Augustus Stone, the play follows the title character Metamora, a heroic and noble American Indian chief, and his tragic fall at the hand of English settlers in seventeenth century New England.

Napoleonic Wars: (1803-1815) a series of major conflicts between the French Empire, led by Emperor Napoleon I, against several European nations.

noble savage: in literature, an idealized concept of uncivilized man, who symbolizes the innate goodness of one not exposed to the corrupting influences of civilization.

Non-Importation Act of 1806: passed by Congress, the act banned certain imports from Britain as an attempt to counteract British violations of neutrality.

re-exported: the process of repackaging foreign goods in American ports.

Rule of 1756: a British policy enacted during the Seven Years’ War (the conflict is known as the French and Indian War in America) which specified that Britain would not do trade with neutral countries who also traded with the enemy.

Tecumseh: (1768-1813) Shawnee Indian political leader and leader of the pan-Indian coalition, known as Tecumseh’s Confederacy which, joined by British forces, fought against the United States during the War of 1812.

Tippecanoe and Tyler Too: the campaign slogan of William Henry Harrison (“Tippecanoe”) and his vice presidential running-mate John Tyler.

Trail of Tears: (1838-39) the forcible removal of several Indian tribes (namely, Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and Chickasaw) from their homeland to reservations west of the Mississippi River by the United States government, following the enactment of the Indian Removal Act.

William Henry Harrison: (1773-1841) Ninth President of the United States. He gained recognition during the Battle of Tippecanoe, where his tactical victory over the Indians would earn him the nickname “Tippecanoe.”

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 4 – Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

- Standard 1A – The student understands the international background and consequences of the Louisiana Purchase, the War of 1812, and the Monroe Doctrine.

- 5-12 – Analyze Napoleon’s reasons for selling Louisiana to the United States.

- 9-12 – Analyze how the Louisiana Purchase influenced politics, economic development, and the concept of Manifest Destiny.

- 5-12 – Explain President Madison’s reasons for declaring war in 1812 and analyze the sectional divisions over the war.

- 5-12 – Assess why many Native Americans supported the British in the War of 1812 and the consequences of this policy.

- Standard 1B – The student understands federal and state Indian policy and the strategies for survival forged by Native Americans.

- 7-12 – Compare the policies toward Native Americans pursued by presidential administrations through the Jacksonian era.