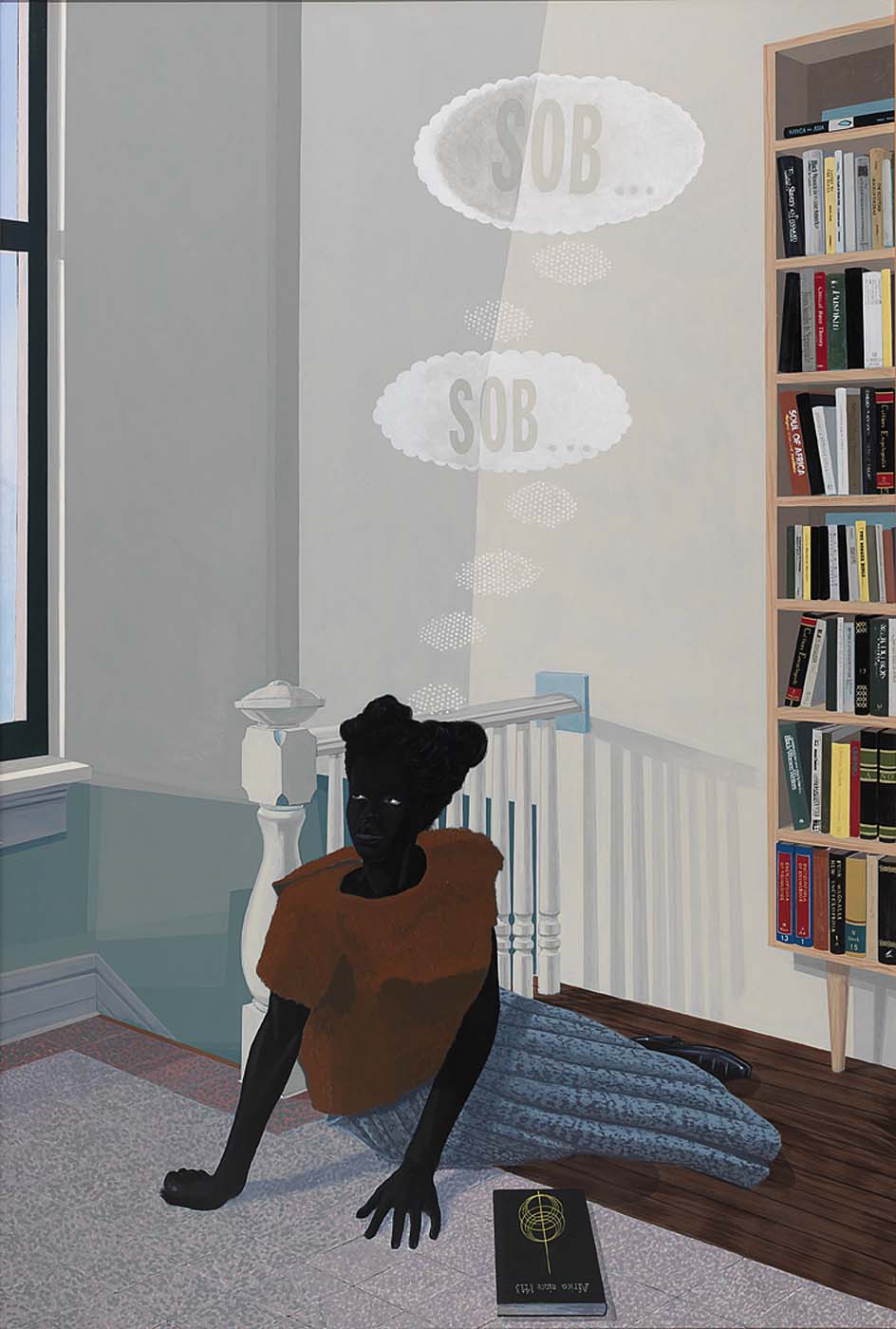

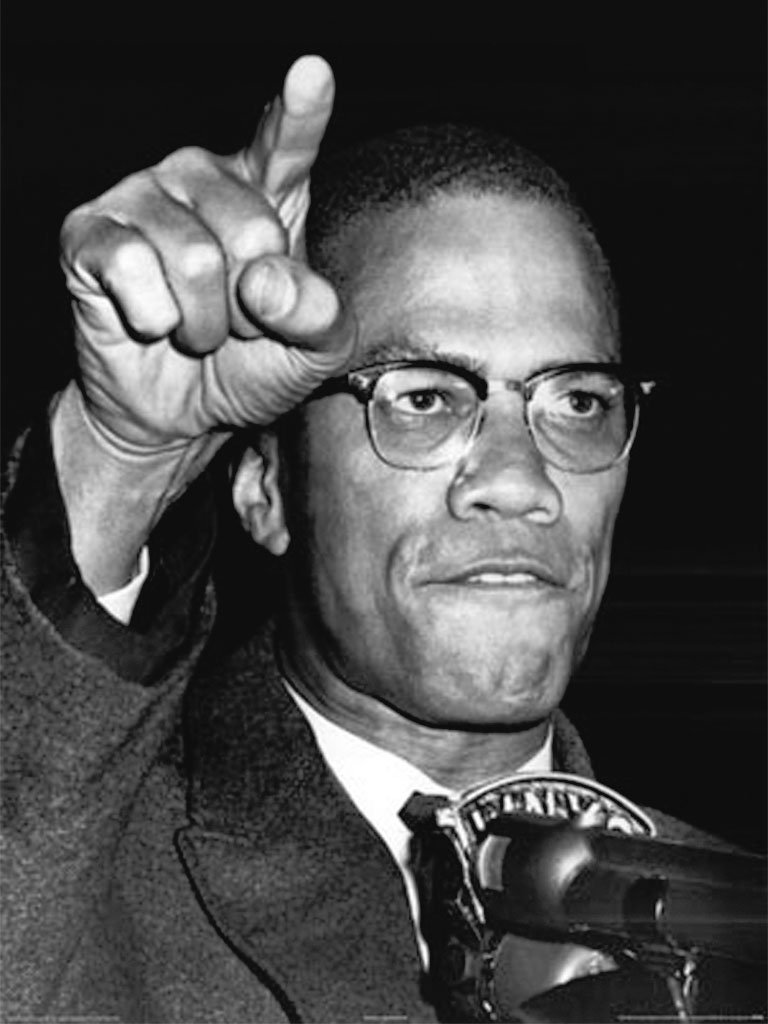

Following the turbulent era of the African American Civil Rights movement, artist Kerry James Marshall tackles the issue of identity and ponders the future of the race with an image of a young black girl in his painting, SOB, SOB. She sits among books that tell the history of African and African American history and culture. Despite her sorrowful thoughts as she ponders her people’s turbulent history, she gazes out the window to the outside world in a hopeful gesture. She is emblematic of the new generation of African Americans who will go forward with a wealth of knowledge gained from the past. Many of the books on the shelf address the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s of which African American rights activist Malcolm X was involved. Malcolm X is remembered through the artwork By Any Means Necessary. The title references part of a speech given by Malcolm X that encapsulates his philosophy, stating, “We declare our right on this earth to be a man, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.” Paired together, these artworks elucidate the journey of the Civil Rights Movement, then and now.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

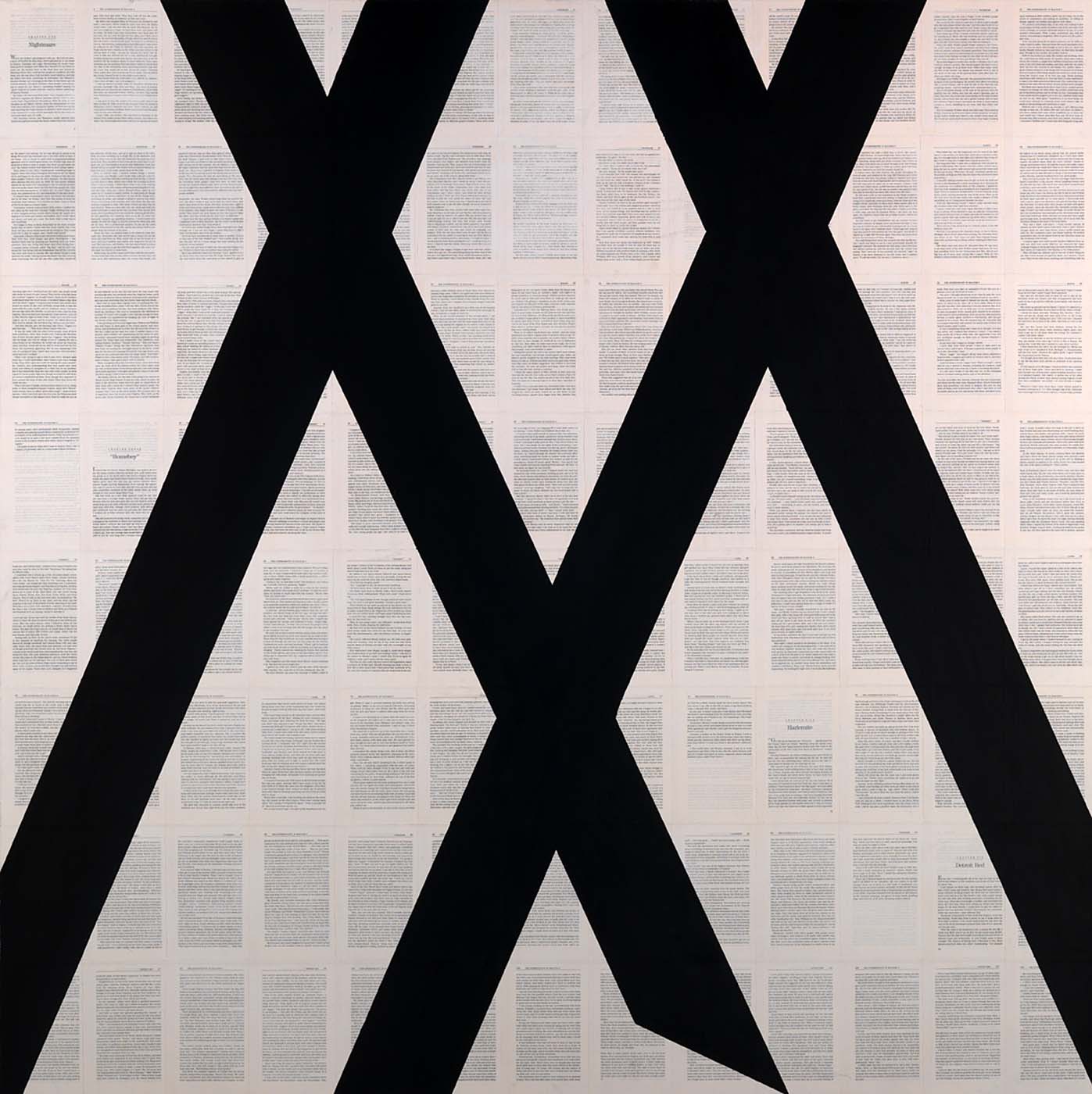

By Any Means Necessary (after Malcolm X)

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What information can we learn about Malcom X, his ideas, and their influence today from this painting? What clues do Tim Rollins and K.O.S. give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

What do you notice about the bold black lines that crisscross the image?

What do you notice about the bold black lines that crisscross the image?

Four thick diagonal lines form both the letter “M” and three “X”’s across the painting. The “M” and “X” represent the initials of Malcolm X. While three lines seem to continue beyond the canvas, one line ends in a sharp, scalpel-like point at the bottom edge of the work.

What do you see in the background?

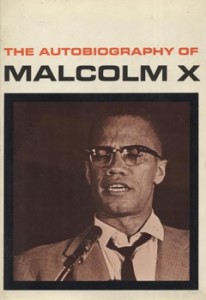

Wallpapering the painting beneath the black diagonals lie eight rows of sequential book pages. Collaged onto the surface of the canvas are chapter’s one through six of the Autobiography of Malcolm X (As Told to Alex Haley). These chapters focus on Malcolm X’s early years – his childhood in Michigan and early adulthood in Boston and Harlem.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Malcolm X was a powerful figure in the Civil Rights movement. His autobiography documents his life and the evolution of his views about how African Americans should overcome oppression and exploitation. The title of the painting, By Any Means Necessary, is a quote often used by Malcolm in public speeches to challenge his listeners to organize and take action to gain their rights, respect and freedom: “We want freedom by any means necessary. We want justice by any means necessary. We want equality by any means necessary.” This quote was used in one of his last speeches at the Ford Auditorium in Detroit on February 14, 1965 the day his home was firebombed and only days before his was shot and killed at the Audubon Ballroom in New York.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X (as told to Alex Haley), published in 1965, was banned from many high schools during the height of Civil Rights movement for its controversial promotion of racial equality through violence. The black lines crossing over the text in the painting function both as a monogram for Malcolm X, and as censors to the text. The sharp ending of one of the four lines creates a visual symmetry that indicates a disruption. Does it reflect the abrupt ending of Malcolm X’s life? Could it indicate Malcolm’s intent to break the cycle of social injustice by the use of sharper tactics?

The artists who created this work are Tim Rollins and Kids of Survival, or K.O.S. Rollins first formed K.O.S. with a group of high school students he was working with while teaching in the South Bronx. Many of the works of Rollin and K.O.S. focus on reading literary classics, exploring their meaning and connections to contemporary life, and deconstructing them in the process of creating a new visual interpretation of the piece.

SOB, SOB

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. How does SOB, SOB provoke the viewer to reflect on the African American experience of the past, present, and future? What details does Kerry James Marshall include for us to consider in our reflection? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

What do you notice about the figure in the painting, her pose, expression, and where she is positioned in her setting?

The female figure lies awkwardly on the floor in a room at the top of a flight of stairs. She seems hemmed in by the railing and the enclosed space of the room, while she gazes out the window. While her face remains contemplative, her fist and claw-like open hand register strong emotion, possibly anger over what she has just read.

What book is the young woman reading? What others are on her bookshelf?

The book on the floor is Africa Since 1413, an account of the effects of European colonization on the African continent, its cultures and peoples. The bookshelf is full of other volumes on African history.

Think about the title of the work, SOB, SOB.

A sob is a deep cry of despair. Here, in written in capital letters in thought bubbles, it might also refer to a pointed expression of anger.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Kerry James Marshall is known for his monumental images of African American history and culture. In SOB, SOB, we see a figure who is very much aware of her cultural history and deeply affected by it.

Christina’s World, 1948, Andrew Wyeth, oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art (MOMA)

The artist based the young woman’s pose on that of the female figure in Christina’s World, a painting by Andrew Wyeth, in which a young paralyzed woman faces a physical challenge in getting up a hill. Marshall has taken Christina’s pose and completely reversed it; the young black girl is shown from the front, not the back and she is indoors, not outdoors. How does this inversion imply looking to a past instead of a future like in Christina’s World? What connection can you make between the two figures’ inner thoughts and struggles? How do you think their past experiences and cultural history have shaped the figures’ lives and views of the future? Based on the black girl’s cultural history, what challenges might she expect to find as she moves forward in her life?

SOB, SOB evokes Marshall’s intellectual journey over the last fifty years beginning with his boyhood visits to the local library. According to the artist, by the third and fourth grades he knew “every single art book in the library,” and by the seventh grade he was taking summer classes at the Otis Art Institute. He was greatly influenced by reading and books as a young man and his art today is an ongoing exploration of African American history. How do you think the books on this shelf inform the reader and her perspective on life? How might they be valuable, weighty, or empowering to her?

The woman, her expression, and her future are as ambiguous as the title of this painting. Where can this woman go in her world – be it the one in the painting, or the one experienced by African Americans in this country? Will her life become another volume of struggle like those on her bookshelf? Or will their histories empower her?

Historical Background

Voices of a Generation: Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King delivers the “I have a dream” speech from the podium at the March on Washington, 1963, Bob Adelman, Library of Congress

Martin Luther King Jr. first became a prominent voice in the Civil Rights movement in 1955 when, as a new pastor in Montgomery, Alabama, he agreed to head the Montgomery Improvement Association. The organization was formed to coordinate the Montgomery bus boycott, prompted by the arrest of Rosa Parks for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger. King was the primary representative for the group during the boycott, and was able to succeed by using protest strategies that involved mobilizing the African-American community through their churches and utilizing the non-violent protest methods of Indian civil rights activist Mahatma Gandhi.

As Civil Rights protests spread throughout the South and eventually the nation, King continued to combine peaceful methods of protest and his theological training to work toward the goal of equal rights for African Americans. On August 28, 1963, King participated in the March on Washington, where 250,000 black and white people rallied in support of the civil rights bill that was pending in Congress. Near the end of the day at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial, Martin Luther King Jr. made his now-famous “I Have a Dream” speech. His words, echoing the Bible and the Constitution, expressed hope that his dream of equality for all people would someday be realized.

Malcolm X first became involved in the Civil Rights Movement when, after a stint in prison, he turned his life around and aligned himself with the Nation of Islam. His siblings had written to him in prison, expounding the beliefs of the new religious movement, which preached a complete separation of the races as the solution to the problems faced by black Americans. It preached self-reliance, non-destructive behavior, strict discipline, and advocated for the eventual return of blacks to Africa in order to truly be free from white supremacy. In 1950, a fully-converted Malcolm replaced his birth surname “Little” with “X,” explaining that “X” symbolized the African family name that he would never know. In his autobiography he wrote, “For me, my ‘X’ replaced the white slavemaster name of ‘Little’ which some blue-eyed devil named Little had imposed upon my paternal forebears.”

While both men emerged as prominent voices in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X differed in their philosophies and approaches to solving racial inequality. King’s promotion of non-violent, direct-action efforts for complete integration and the achievement of full civil rights ran contrary to that of his fellow activist. Malcolm X promoted complete separation of the races, rejecting any form of integration, and opposed King’s philosophy of non-violence as a means of protest. Malcolm X equated King’s non-violent philosophy to being defenseless against white racism. The two men also differed in matters of religion, which heavily guided both of their philosophies. King, a Christian Baptist pastor, led the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and preached his message in churches. Malcolm X was a convert to the Nation of Islam and significantly raised the religious movement’s profile, preaching his message first on street corners and then moving to larger venues as the movement grew in popularity.

In a television interview, psychology professor Dr. Kenneth B. Clark discussed with King his philosophy of non-violence and why King believed that it was the best method to enact change for the African American community. King explained that “Non-violent direct action is a method of acting to rectify a social situation that is unjust and it involves in engaging in a practical technique that nullifies the use of violence or calls for non-violence at every point. That is, you don’t use physical violence against the opponent. . . . I think that non-violent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and human dignity. It has a way of disarming the opponent. It exposes his moral defenses. It weakens his morale and at the same time it works on his conscience. He just doesn’t know how to handle it and I have seen this over and over again in our struggle in the South.”

Clark then addressed the differences between King and Malcolm X, calling attention to the fact that Malcolm X had criticized King’s method of non-violent opposition by saying King’s philosophy “plays into the hands of the white oppressors, that they are happy to hear [King] talk about love for the oppressor because this disarms the Negro and fits into the stereotype of the Negro as a meek, turning-the-other-cheek sort of creature.” King replied, “I don’t think of [love] as a weak force, but I think of [it] as something strong and that organizes itself into powerful direct action. Now, this is what I try to teach in this struggle in the South: that we are not engaged in a struggle that means we sit down and do nothing; that there is a great deal of difference between non-resistance to evil and non-violent resistance. Non-resistance leaves you in a state of stagnant passivity and deadly complacency, where non-violent resistance means that you do resist in a very strong and determined manner, and I think some of the criticisms of non-violence or some of the critics fail to realize that we are talking about something very strong and they confuse non-resistance with non-violent resistance.” While King did state the differences between himself and Malcolm X, he refused to debate him publicly, not wanting his work to be jeopardized and thrown in a negative light by one who was all too eager to do so. For his part, Malcolm X publicly denounced Martin Luther King many times, calling the preacher a modern-day Uncle Tom stating that “By teaching them to love their enemy, or pray for those who use them spitefully, today Martin Luther King is just a 20th century or modern Uncle Tom, or a religious Uncle Tom, who is doing the same thing today, to keep Negroes defenseless in the face of an attack.”

In time, Malcolm X would become less confrontational with King and his philosophies, due in part to his growing estrangement with the Nation of Islam. Tensions grew when Malcolm X and the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammed, differed on the Nation’s response to a shooting of a Nation member by the Los Angeles Police Department in 1962; Malcolm X demanded action while Muhammed advocated caution and patience. The disagreement came to a head the following year in 1963 when it was revealed that Muhammed had been carrying on extra-marital affairs – a serious violation of the Nation of Islam’s strict teachings. Dismayed by Muhammed’s hypocrisy and realizing the Nation’s limitations due to its stringent doctrine, Malcolm X broke with the movement in 1964.

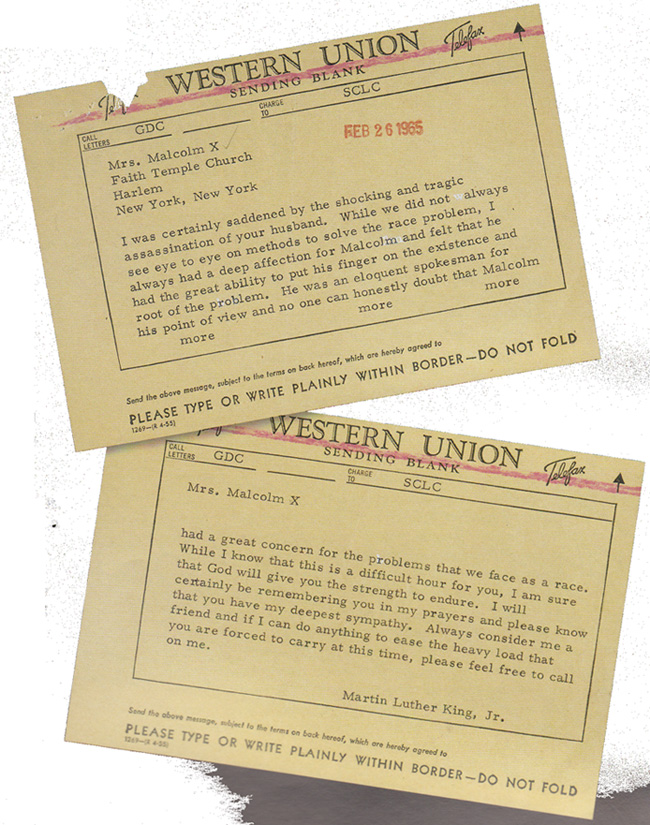

After Malcolm X broke ties with the separatist Muslim movement, he began to speak more reverently of the viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. He publicly acknowledged, “Dr. King wants the same thing I want – freedom!” This new perspective prompted Malcolm X to arrange a meeting with King, but the meeting never happened. It was scheduled for Tuesday, February 24, 1965, but two days earlier Malcolm X was assassinated by Nation of Islam members. In a letter to Malcolm X’s wife following his assassination, King acknowledged their differing philosophies, writing, “While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had a great ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem. He was an eloquent spokesman for his point of view and no one can honestly doubt that Malcolm had a great concern for the problems that we face as a race.”

Primary Source Connections

Telegram from Martin Luther King Jr. to Betty al-Shabazz, wife of Malcom X, offering condolences on her husband’s assassination. February 26, 1965.

Telegram from Martin Luther King Jr. to Betty al-Shabazz, wife of Malcom X, offering condolences on her husband’s assassination. February 26, 1965.

“I was certainly saddened by the shocking and tragic assassination of your husband. While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had the great ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem. He was an eloquent spokesman for his point of view and no one can honestly doubt that Malcolm had a great concern for the problems that we face as a race. . . .”

Literary Connections

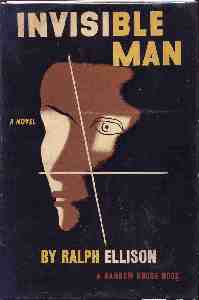

Invisible Man, 1952, Ralph Ellison

Invisible Man, 1952, Ralph Ellison

A milestone book in African American literature, Invisible Man is a first-person account of a young black man’s experiences growing up in a Southern black community, attending college, and moving to New York. The unnamed man claims that he is an “invisible man,” that is that others refuse to “see: him because he is African American.

Listen to Ralph Ellison describe his process of discovery as he worked on Invisible Man

The Autobiography of Malcolm X, 1965, Malcolm X with Alex Hayley

Journalist Alex Hayley co-authored this book with Malcolm X, based on a series of interviews between the two. The book is written in first-person narrative in the voice of Malcolm X, who relays his thoughts and actions growing up in Michigan, to his involvement with the Nation of Islam. The epilogue is written solely by Hayley, who recounts the time period after Malcolm X’s assassination.

The Rose That Grew from Concrete, 1999, Tupac Shakur

A series of poems written by the late rapper in his teenage years, the poems cover subjects ranging from inner-city poverty, the African American experience in America, and his dreams and aspirations.

(Harlem) A Dream Deferred, 1951, Langston Hughes

In 1951, the year of the poem’s publication, the mood characterizing American blacks was frustration. Despite the passage of laws which enabled blacks to vote and to own property, there remained a continued prejudice against blacks which effectively relegated them to second-class citizenship. They were not afforded the same opportunities in education or in employment as whites. Schools were segregated and poorly equipped without proper supplies, employment opportunities were relegated to menial jobs such as shoe-shiners, ditch-diggers, porters, and domestic servants. By the 1960s, the frustration had reached a boiling point, foreshadowed by Hughes in the last line of his poem.

Artwork Connections

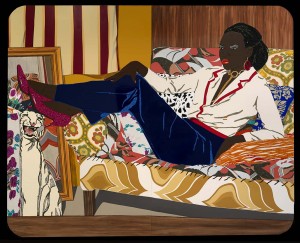

Portrait of Mnonja, 2010, Mickalene Thomas

Portrait of Mnonja, 2010, Mickalene Thomas

Mickalene Thomas’ work explores notions of beauty, sexuality and black female identity. Her use of rhinestones and vivid textile patterns adds an even greater sense of drama and sensuality to her paintings. For Thomas, the rhinestones evoke folk art traditions and Haitian voodoo art. They also serve as a metaphor for female beauty products, which can both enhance and mask a woman’s identity.

The reclining figure is posed in a sassy contrapposto and situated against a wood-paneled background redolent of a seventies-era living room. Her right hand rests on her knee, revealing nail polish that matches her audacious pink heels. She exudes dignity and self-assurance.

Top of the Line (Steel), 1992, Thornton Dial, Sr.

This piece is Dial’s response to the social outbreak of the Los Angeles riots in 1992—among the largest civil disturbances in American history. Painted figures loot parts of air conditioners, cars, and other consumer goods. His frenzied brushstrokes convey the intensity of the mob. The title has a double meaning, referring to the quality of the stolen merchandise and the socioeconomic struggle for equality. “Steel” also plays on the word “steal,” pointing to Dial’s experience as a steelworker and the looting that took place during the riots.

Soundsuit, 2009, Nick Cave

Nick Cave started making soundsuits as a form of self-reflection in the early 1990s. He was deeply troubled by the Rodney King beating and Cave made his first suit out of found twigs as a way to shield and protect his identity as a black man. Trained as a dancer and an artist, Cave realized that the suit made noise when worn and has since made hundreds of soundsuits of almost every imaginable material. In a recent interview with The Washington Post, Cave referred to his suits as a barricade between him and the outer world. In shielding the wearer’s identity, Cave also allows that person to be completely their self and anonymous. Each person brings a unique identity to the suit. – Eye Level, Smithsonian American Art Museum

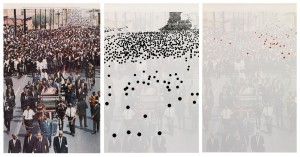

Life Magazine, April 19, 1968, 1995, Alfredo Jaar

Alfredo Jaar took a photograph of Martin Luther King’s funeral from an issue of Life magazine and graphically depicted African Americans walking in the crowd behind King’s coffin. Next to it he showed whites in that same crowd. His triptych both simplifies and comments on America at the time of Martin Luther King’s death in 1968. – Eye Level, Smithsonian American Art Museum

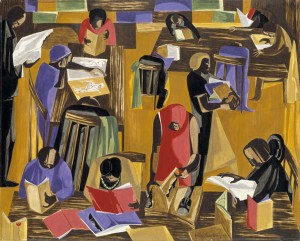

The Library, 1960, Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence researched many of his paintings of African American events by reading history books and novels. Looking back at his high school years, he remembered that black culture was “never studied seriously like regular subjects,” and so he had to teach himself by visiting libraries and museums. This colorful view of a crowded reading room may show the 135th Street Library—now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture—where the country’s first significant collection of African American literature, history, and prints opened in 1925. Everybody appears absorbed in their books, and the standing figure in the front looking at African art may represent the artist as a young man, delving deeper into his heritage.

Identification Manual, 1964, Larry Rivers

Identification Manual combines phantom images of murdered civil rights marchers with pictures of beautiful black women and products designed to bleach dark skin. On the right, two sliding panes of glass afford different racial identities to a figure of a woman.

A white artist (Rivers) creating racially explicit art in the 1960s was controversial, and Rivers liked to give his works clinical, deadpan titles that made the images even more shocking. Identification Manual conveys the difficulty faced by blacks and whites trying to find their way through the heated conflicts of the civil rights movement. A quotation from Lord Acton, a famously liberal historian in nineteenth-century England, accompanied the title. It read: “The most certain test by which we judge whether a country is really free is the amount of security enjoyed by minorities.”

A Dream Deferred, 2010, Kara Walker

Black & White, 1993, Byron Kim and Glenn Ligon

This collaboration between artists Byron Kim and Glenn Ligon is a grouping of thirty-two small monochromatic paintings based on skin tones; sixteen versions of black skintone straight out of the paint tube and sixteen versions of white skintone straight out of the paint tube. Black & White exploits the notion of “flesh tone” as a color and the prejudices of art materials, specifically tubes of paint labelled “Flesh” to connote “white” or “tan” skintones.

Media

Meet the Artist: Kerry James Marshall (8 min)

An interview with artist Kerry James Marshall at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Kerry James Marshall is one of the leading contemporary painters of his generation. Over the past twenty-five years, he has become internationally known for monumental images of African American history and culture.

The Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. (5 min) From The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era, and Beyond – Smithsonian American Art Museum

A selection of paintings, sculpture, prints, and photographs by forty-three black artists who explored the African American experience from the Harlem Renaissance through the Civil Rights era and the decades beyond, which saw tremendous social and political changes.

Subject: History

Why Malcolm X Still Speaks Truth to Power – Smithsonian Magazine

Malcolm X remains a towering figure, whose passionate writing have enduring resonance.

Subject: Music

Voices of Struggle: The Civil Rights Movement, 1945 to 1965 – Smithsonian Folkways

We honor African-American history and music with a look at the profound cultural contribution of the Civil Rights Movement, called by Guy Carawan “the greatest singing movement this country has experienced.” The African American struggle for civil rights and equality inspired the many other socio-political movements in the USA and around the world.

Say it Loud: African American Spoken Word – Smithsonian Folkways

The spoken word occupies a central and indispensable position in African American history and culture. As a vessel for remembrance, the oral tradition carried African narratives to a new continent and sustained them through bondage; as a political catalyst, speech defined the struggle for freedom and moved ordinary people to extraordinary acts of courage; and as an art form, the word has conveyed itself forcefully and dramatically by drawing on the rich African American musical heritage. The Smithsonian Folkways archives contain an unparalleled range of examples of African American spoken word recordings that express the richness, complexity, and diversity of African American oral traditions.

Glossary

Dr. Kenneth B. Clark: (1914-2005) African American psychologist best known for his work on race relations.

Elijah Muhammed: (1897-1975) African American Muslim religious leader, led the Nation of Islam from 1934 to 1975; mentor to Malcolm X.

I Have a Dream: a speech given by Martin Luther King on August 28, 1963 at the conclusion of the March on Washington. It is widely regarded as one of the most important speeches in American history.

Mahatma Gandhi: (1869-1948) Indian political and spiritual leader during India’s struggle for Independence from Great Britain. Known for his peaceful, passive, non-violent forms of protest.

March on Washington: a political rally held on August 28, 1963 in Washington, D.C. More than 250,000 people gathered for the rally, organized by civil rights and religious groups. The march concluded with martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Montgomery bus boycott: organized by Martin Luther King Jr., the boycott began in 1955 following the arrest of Rosa Parks. It began a chain reaction of boycotts throughout the South.

Montgomery Improvement Association: the organization was formed following the December 1955 arrest of Rosa Parks to oversee the Montgomery bus boycott.

Nation of Islam: an Islamic religious movement founded in Detroit, United States in 1930, led by Elijah Muhammed. It’s most famous member was Malcolm X.

Rosa Parks: (1913-2005) African American civil rights activist; refused to surrender her bus seat to a white passenger, which spurred the Montgomery bus boycott and other efforts to end segregation

Southern Christian Leadership Conference: an African-American civil rights organization; closely associated with its first president, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Uncle Tom: an epithet for a person who is slavish and excessively subservient to perceived authority figures, particularly a black person who behaves in a subservient manner to white people; or any person perceived to be complicit in the oppression of their own group. Derives from the African American character “Uncle Tom” from the 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards

Era 9: Post War United States (1945-early 1970s)

Standard 4A –The student understands the “Second Reconstruction” and its advancement of civil rights.

- 7-12 – Explain the origins of the postwar civil rights movement and the role of the NAACP in the legal assault on segregation.

- 5-12 – Evaluate the Warren Court’s reasoning in Brown v. Board of Education and its significance in advancing civil rights.

- 5-12 – Explain the resistance to civil rights in the South between 1954 and 1965.

- 7-12 – Analyze the leadership and ideology of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X in the civil rights movement and evaluate their legacies.

- 7-12 – Assess the role of the legislative and executive branches in advancing the civil rights movement and the effect of shifting the focus from de jure to de facto segregation.

- 5-12 – Evaluate the agendas, strategies, and effectiveness of various African Americans, Asian Americans, Latino Americans, and Native Americans, as well as the disabled, in the quest for civil rights and equal opportunities.

- 9-12 – Assess the reasons for and effectiveness of the escalation from civil disobedience to more radical protest in the civil rights movement.

Historical Thinking Standards

The preceding information supports the following Historical Thinking-based concepts:

Standard 1. Chronological Thinking

- Identify the temporal structure of a historical narrative or story.

- Reconstruct patterns of historical succession and duration.

Standard 2. Historical Comprehension

- Identify the author or source of the historical document or narrative.

- Reconstruct the literal meaning of a historical passage.

- Draw upon the visual, literary, and musical sources.

Standard 3. Historical Analysis and Interpretation

- Compare and contrast differing sets of ideas, values, personalities, behaviors, and institutions by identifying likenesses and differences.

- Consider multiple perspectives of various peoples in the past by demonstrating their differing motives, beliefs, interests, hopes, and fears.

- Analyze cause-and-effect relationships.

- Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues.

- Hold interpretations of history as tentative, subject to changes as new information is uncovered, new voices heard, and new interpretations broached.

- Hypothesize the influence of the past, including both the limitations and opportunities made possible by past decisions.

Standard 4. Historical Research Capabilities

- Formulate historical questions from encounters with historical documents, eyewitness accounts, letters, diaries, artifacts, photos, historical sites, art, architecture, and other records from the past.

- Support interpretations with historical evidence in order to construct closely reasoned arguments rather than facile opinions.

- Identify relevant historical antecedents and differentiate from those that are inappropriate and irrelevant to contemporary issues.

- Evaluate the implementation of a decision by analyzing the interests it served; estimating the position, power, and priority of each player involved; assessing the ethical dimensions of the decision; and evaluating its costs and benefits from a variety of perspectives.