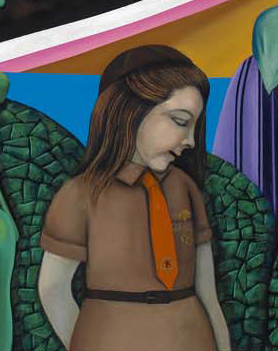

In the first pair of artworks to emerge in the contemporary era, we have two works that deal with the issues of nationality, identity and the assimilation of cultures. Mel Casas’s pun-laced Humanscape 62 combines elements familiar to many Americans: brownie desserts and a young Girl Scout (a Brownie), with traditional Mexican imagery. This pop art style-blend illustrates the Chicano experience to American culture and creates a push and pull narrative about Latino identity. Similarly, Roger Shimomura, an American-born artist of Japanese descent, contemplates repressed emotions from the time he and his family spent in World War II-era Japanese internment camps, following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Humanscape 62

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What message is Mel Casas trying to convey about the way Mexican-American culture is depicted in American media? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Mel Casas has given this painting a subtitle, located at the bottom of the canvas. Where do we see “brownies” in this image? What signs of the Southwest has the artist included?

The subtitle of Humanscape 62 is “Brownies of the Southwest.” The first thing many people see when looking at this image is the gigantic stack of chocolate brownies in the upper region of the painting. They look like they could have been taken from a television advertisement. In the foreground, we see a young junior Girl Scout, or “Brownie,” the term given to Girl Scouts in second or third grade and characterized by the uniform color.

The subtitle of Humanscape 62 is “Brownies of the Southwest.” The first thing many people see when looking at this image is the gigantic stack of chocolate brownies in the upper region of the painting. They look like they could have been taken from a television advertisement. In the foreground, we see a young junior Girl Scout, or “Brownie,” the term given to Girl Scouts in second or third grade and characterized by the uniform color.

We see a Native American in profile on the left-hand side of the painting. The group of women on the opposite side of the painting might be Native American or Mexican-American people of the Southwest. Their garments are reminiscent of rebozos – long, flat shawls or scarves traditionally found in Mexico. The people whose faces we can see have brown skin, raising the question of whether the artist intended to draw a comparison between these “brown” people and the various kinds of “brownies” depicted.

Casas included a very specific pop culture reference in this painting, seen in green integrated into the serpent mosaic at the bottom of the canvas. What is its significance?

Perched atop the double-headed serpent mosaic is the Frito Bandito, the former Fritos corn chips mascot who appeared in late 1960s television commercials for the brand. The Frito Bandito was controversial for its racist depiction of a “Mexican bandit” stereotype, a sombrero-clad criminal on the run from authorities who spoke broken English with an exaggerated Mexican accent. The Frito Bandito was retired as the Fritos mascot in 1971 in response to pressure from the National Mexican-American Anti-Defamation Committee, which claimed the mascot promoted harmful negative stereotypes about Mexican-Americans.

Perched atop the double-headed serpent mosaic is the Frito Bandito, the former Fritos corn chips mascot who appeared in late 1960s television commercials for the brand. The Frito Bandito was controversial for its racist depiction of a “Mexican bandit” stereotype, a sombrero-clad criminal on the run from authorities who spoke broken English with an exaggerated Mexican accent. The Frito Bandito was retired as the Fritos mascot in 1971 in response to pressure from the National Mexican-American Anti-Defamation Committee, which claimed the mascot promoted harmful negative stereotypes about Mexican-Americans.

Casas has integrated the Frito Bandito into an iconic piece of imagery from Latin American culture. The green double-headed serpent mosaic references a well-known Aztec object in the collection of the British Museum, and its iconography has great religious significance in Mexican culture.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

In Humanscape 62, Casas has juxtaposed references to the rich culture and peoples of Mexico and the American Southwest with several references to “brownies” or brownness and a crudely stereotypical Mexican character from American advertising. Using visual wordplay, Casas asks the viewer to question what being “brown” means to different people in different contexts. If Americans’ first reference point for Mexican-Americans is the Frito Bandito, Casas suggests, then the harmful stereotypes risk obscuring the rich culture and peoples of Mexico.

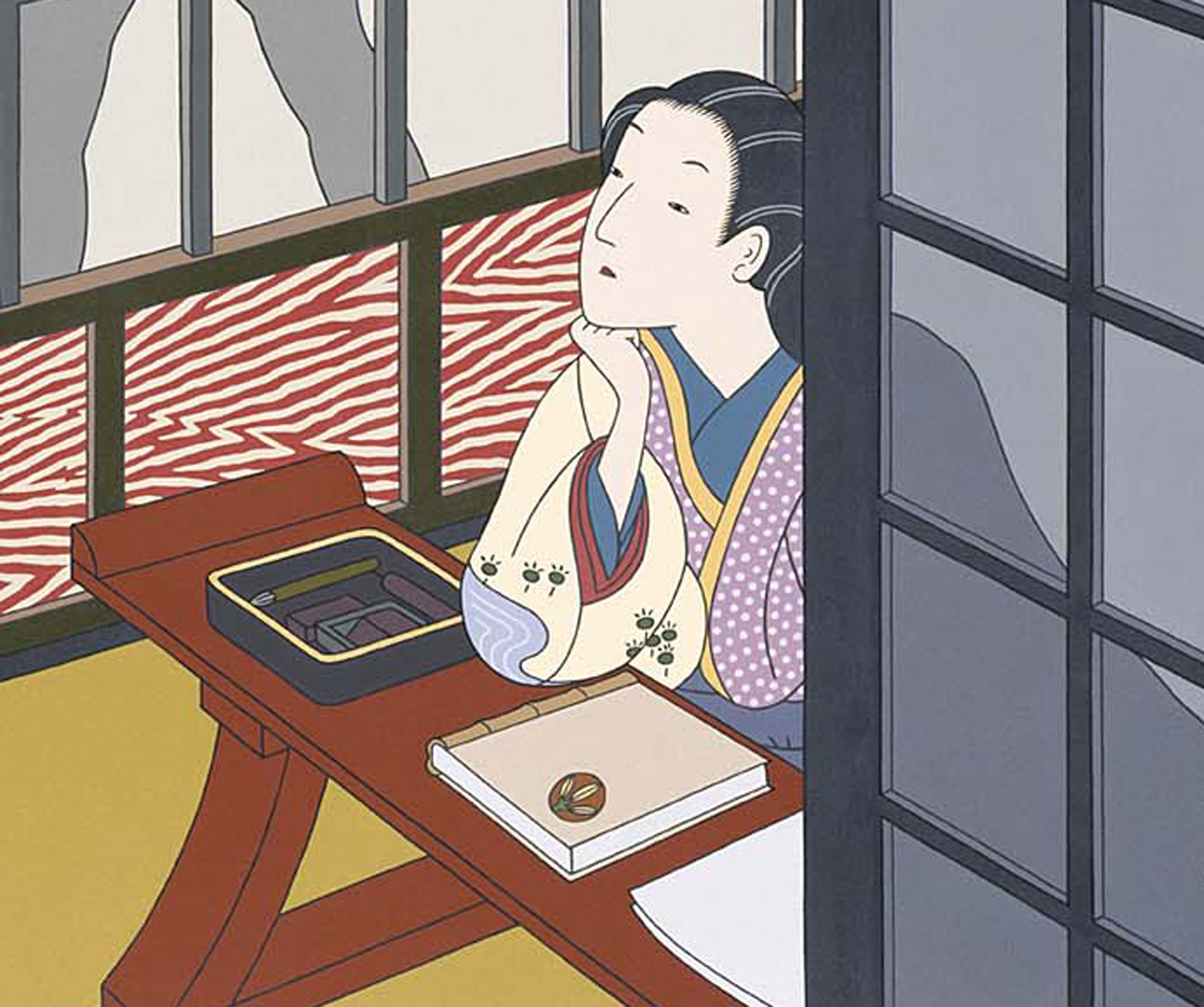

Diary: December 12, 1941

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What can we learn about the experiences of Japanese-Americans in the 20th century from this painting? What clues does Shimomura give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Describe the silhouetted figure behind the screen. What does it remind you of? What kinds of words would you use to describe this figure?

Describe the silhouetted figure behind the screen. What does it remind you of? What kinds of words would you use to describe this figure?

The figure in shadow has a highly muscular frame, and is posed with his hands on his hips and legs spread in a powerful stance. A cape appears to billow out behind him, reminding us of a superhero, and in particular, the iconic comic book hero Superman. Words that come to mind might be “strong,” “heroic,” or “protective.”

Next, take a close look at what is going on inside the screened room. Describe the woman in the center of the painting. What are the objects on the table? What is the setting?

The woman’s features, hair, and kimono suggest that she is Japanese. She rests her chin on her right hand and gazes out the doorway ahead of her, looking pensive. The screen walls surrounding her are traditionally Japanese architectural design elements. There is a writing set, a book, and some paper on the table in front of her. The book does not appear to have a title, and the inclusion of the writing set indicates that the book may be a diary or journal.

The woman’s features, hair, and kimono suggest that she is Japanese. She rests her chin on her right hand and gazes out the doorway ahead of her, looking pensive. The screen walls surrounding her are traditionally Japanese architectural design elements. There is a writing set, a book, and some paper on the table in front of her. The book does not appear to have a title, and the inclusion of the writing set indicates that the book may be a diary or journal.

Shimomura’s painting style recalls ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock prints and paintings from the Edo Period, during the 17th-19th centuries), probably the style that most heavily shaped the West’s perception of Japanese art. Domestic scenes of women were one of the most popular subjects of ukiyo-e prints.

The title of this piece is Diary, December 12, 1941. What is the significance of that date?

December 12, 1941, was five days after the Japanese attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor and four days after the United States’s formal declaration of war against Japan. The date in the painting’s title refers to the date of a diary entry by the artist’s grandmother, Toku Shimomura, which reads (in translation from Japanese):

I spent all day at home. Starting from today we were permitted to withdraw $100 from the bank. This was for our sustenance of life, we who are enemy to them. I deeply felt America’s large-heartedness in dealing with us.

Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the federal government froze the bank accounts of Japanese-Americans, who were seen as posing a potential national security threat. A few days later, the government permitted Japanese-Americans to withdraw small amounts for living expenses. In February of 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order clearing the way for people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast to be forcibly relocated to internment camps. Toku and her family, including a three-year old Roger, were transferred in August of 1942 to the Minidoka Relocation Center near Hagerman, Idaho, where they lived for the duration of the war.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

We see the silhouette of a Superman-like figure standing on the other side of the screen walls that enclose a Japanese woman, gazing pensively with a diary and writing implements placed on the table before her. Looking at the Superman figure on its own, we might interpret it as a heroic or protective presence, but in context, with this iconic symbol of America imposing on a traditionally Japanese environment, our interpretation is a bit more complex. Is he protecting this woman, or is he her captor? Is he a savior, or a threat?

As with many contemporary artworks, additional context helps us interpret the meaning of this painting more fully. Knowing that Roger Shimomura used his grandmother’s diary entry as a basis for creating this piece, we can infer that the Superman-like figure may represent the “large-hearted” American Toku referred to in her diary. With the knowledge that the Shimomura family was relocated to an internment camp by the federal government shortly after this diary entry was written, the “large-hearted” American takes on a certain irony here. Superman is known as the defender of “truth, justice, and the American way”; with this painting, Shimomura challenges us to reconcile these ideals with the reality of one of the most unjust chapters in U.S. history.

By simultaneously referencing ukiyo-e and comic book art, Shimomura draws a parallel between these artistic styles and suggests something about the incongruity of growing up Japanese in the United States, immersed in American culture from birth yet still expected to meet society’s stereotypical expectations of what it means to be Japanese. While some cultural stereotypes may seem harmless on the surface, the internment of approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the United States – 62% of them U.S. citizens – illustrates what can happen when stereotypes and racism are allowed to go unchecked.

Historical Background

Japanese American Internment

Roger Shimomura, a Japanese American artist, and his family were interned at a relocation camp during World War II. In the early 1980’s, Shimomura created twenty-five paintings in the Diary series, based on the diary of his grandmother’s experience as an internee at the Minidoka Relocation Center near Hagerman, Idaho. The date of December 12th in the title of the painting refers to an entry in Toku Shimomura’s (1888-1968) diary. The entry reads, “I spent all day at home. Starting from today we were permitted to withdraw $100 from the bank. This was for our sustenance of life, we who are enemy to them. I deeply felt America’s largeheartedness in dealing with us.”

The Shimomura family immigrated to the United States in 1912 during the height of twentieth century Japanese immigration from 1900-1920. Immigration presented Japanese citizens with many challenges due to many legal restrictions and frosty relations between the two nations. Once in the United States, Japanese immigrants were subject to racial prejudice and hostility, which only intensified as many Japanese found success and prosperity in their new country. This prejudice manifested into laws which denied Japanese citizenship and barred them from owning property. Their ineligibility for naturalized citizenship stemmed from the Naturalization Act of 1906, which allowed only the naturalization of “free white persons,” and “persons of African nativity or persons of African descent.” The Asian Exclusion Act of 1924 effectively ended the wave of Japanese immigration because it set quotas for individual countries based on the number of its foreign nationals living in the U.S.

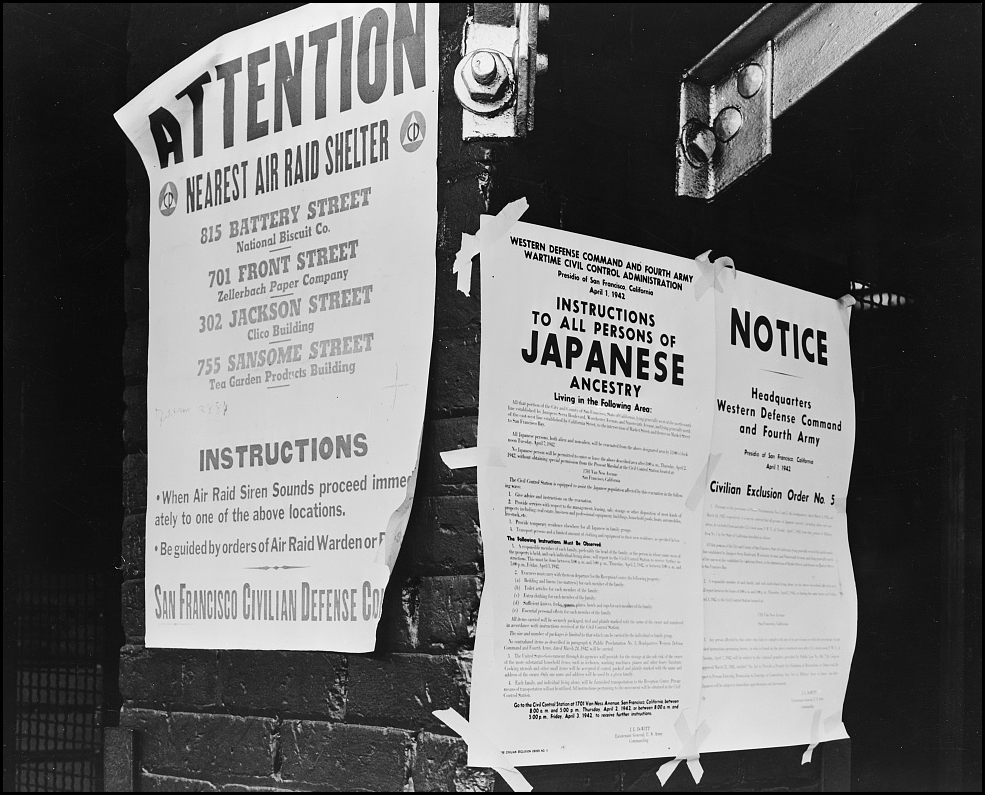

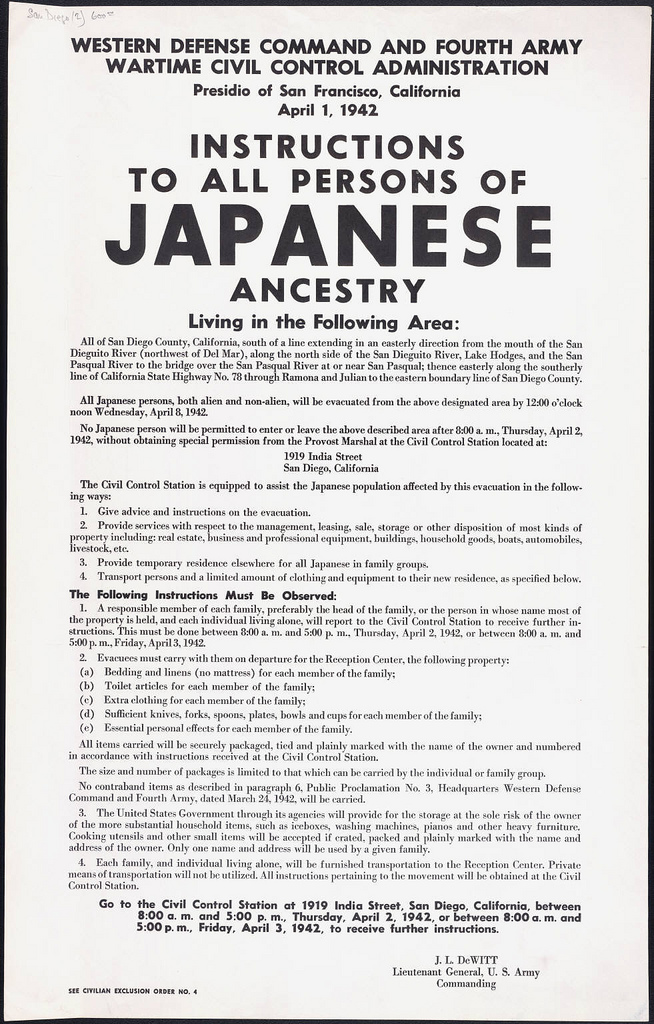

Civilian exclusion order #5, posted at First and Front streets, directing removal by April 7 of persons of Japanese ancestry, from the first San Francisco section to be affected by evacuation. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor resulted not only in the entry of the United States into World War II, but also in the internment of nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. The attack had brought the long-simmering racial prejudice and hostility against Japanese to the surface, boiling over into mass hysteria. Arrests began as soon as the night of December 7, 1941, when FBI agents, and local and military police took Japanese believed to be spies into custody. By December 11 the number of those taken had reached 1,300. Those detained were community leaders, Shinto and Buddhist priests, newspaper reporters, Japanese language teachers, and any who had ties to suspected Japanese publications. Actual evidence of criminal or subversive activities was not necessary for arrest or imprisonment, simply suspicion was enough. Internee Margaret Takahasi recalled the anxious environment:

After Pearl Harbor we started to get worried because the newspapers were agitating and printing all those stories all the time. And people were getting angrier. You kept hearing awful rumors. You heard that people were getting their houses burned down and we were afraid that those things might happen to us. My husband worried because he didn’t know if people would kick him out of his jobs. You didn’t know when the blow was going to fall, or what was going to happen. You didn’t quite feel that you could settle down to anything. Your whole future seemed in question. The longer the war dragged on, the worse the feeling got. When the evacuation order finally came I was relieved, Lots of people were relieved, because you were taken care of. You wouldn’t have all this worry.

Those Japanese Americans who were detained shortly after Pearl Harbor were mostly of the generation called Issei – those who had been born in Japan and moved to the United States. The children of the Issei, born in America, were called Nisei – automatically American citizens by virtue of their birth in the United States. Chiye Tomihiro, a Nisei, believed that her government would protect her, even after her father was arrested and sent to a prison camp:

We used to argue with our parents all the time because we’d say ‘Oh, we’re American citizens. Uncle Sam’s going to take care of us, don’t worry.’ . . . We were so damn naïve. I don’t think any of us ever believed it would happen to us, I think even as we were being hauled away we didn’t believe it was happening to us. . . . We were just like in a trance. . . . We were all taught in the history books that our rights were going to be protected and all this other stuff. And I think that the feeling of having been betrayed is the thing that really makes me the saddest of anything.

Arcadia, California. Military police on duty in watch-tower at Santa Anita Park assembly center, 1942, Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Mass internment of Japanese Americans did not begin until February 19, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing military authorities to exclude “any and all persons” from designated areas of the country as necessary for national defense. While the order did not explicitly reference Japanese Americans, they were the clear targets of the military order. The law established ten relocation centers in the western part of the country to house Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were native-born. The internment of Japanese Americans was the result of the fear the Japanese would attack the mainland and of longstanding anti-Asian sentiment on the West Coast that began when Chinese labor was imported in the 1850s and that was reflected in the 1924 Immigration Act specifically excluding Japanese. Japanese Americans, it was argued, could not be trusted (many German Americans and Italian Americans were also seen as suspect, but not subjected to relocation and internment). Racist wartime propaganda further exacerbated fears of invasion and prejudice against people of Japanese descent. Support for internment also came from local white farmers and businessmen, who assumed possession of most of the internees’ property.

Oakland, California. Baggage of evacuees of Japanese ancestry piled on the sidewalk, 1942, Dorothea Lange, Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Internees were usually not given much advanced notice before their departure, leaving little time to pack or sell household goods, or to locate storage for personal possessions. They could only take with them what they could carry. Those items that could not be taken to the camps were sold at a fraction of their cost. Family pets were left behind.

The first stop for most internees were one of sixteen assembly centers in Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington State. Public facilities like racetracks and fairgrounds were converted into the assembly centers. The internees remained at these assembly centers until the camps were ready. Roger Shimomura spent his third birthday in the Puyallup Assembly Center on the state fairgrounds near Seattle, where Japanese Americans from Seattle were forced to go in April 1942. These assembly centers were hastily converted, with sanitation, food, and health care facilities well below standard. Many internees had to stay in these centers for months as more permanent camps were constructed. Akiko Mabuchi was sent to the Tanforan Racetrack Assembly center and recalled her new residence, which just a week before had been occupied by a horse:

There were bugs and straw all around and we could see our neighbors through the cracks in the stall and hear conversations in the next stall. We slept on straw mattresses. My father made a big mistake when he tried to wash the floor. The dung beneath the boards smelled to high heaven. The latrines were a culture shock. There were two rows of toilets facing each other with no doors. When one flushed, they all flushed. There was no privacy in the showers either. At first we walked across the racetrack to the grandstand for our first meals. It was canned beans and canned wieners, and more beans and more wieners. Later mess halls were built and staffed by our own cooks and food got better. For diversion, we mainly hung out in front of the barracks and talked to pass the time away, or played cards. We had nothing to do.

Toku Shimomura with grandson, Roger, circa 1940. Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

In August 1942, Roger Shimomura and his family traveled by train to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho – one of ten relocation camps ran by the War Relocation Authority on the West Coast. Conditions varied from camp to camp depending on location – from the heat and dust of the Manzanar camp in California, to the bitter winter cold at the Minidoka camp in Idaho. The one factor that all ten camps had in common was their geographic isolation. Shimomura remembers little from that period, but recalls that adjusting to the harsh Idaho winter was difficult. “I’d never experienced heat like that. I had never experienced wind like that, and the sandstorms. And I never remembered ice like that, and the flooding, how everything just turned into this quagmire. It was all new to me.”

Each camp was like a small city – Minidoka had 9,397 inmates in 1943 and was divided into 35 residential blocks of 12 barracks. The camp had its own hospital and schools as well as shops. Families had small apartments in the barracks. Inmates worked in jobs in the camp and eventually some were allowed to leave camp grounds for work, mostly on nearby farms. Shimomura’s father, Eddie Kazuo Shimomura, a pharmacist, worked at the hospital. Later, the federal government established work-release programs which allowed some inmates to leave the camp to find work in Eastern cities or to attend university.

Most Japanese Americans accepted their internment, fearing reprisals, but a small group, known as the No-No Boys resisted. The epithet refers to the protestors’ answering “no” to two questions on the “loyalty questionnaire,” or Leave Clearance Application Form. The questions asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?” and “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any of all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, to any foreign government, power, or organization?” Japanese internees who had proclaimed themselves loyal began the load road of returning to a normal life, either through the work-release program or through military service. Those who took issue with the loyalty questionnaire were condemned to further isolation, and relocated to the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California.

After the war had ended, the last of the internment camps closed in 1946. Many Japanese-Americans returned to their hometowns, but in the years that they had been interned, many had lost their homes, businesses, and belongings and were forced to rebuild their lives. At the time, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes wrote to President Roosevelt about his objections to the relocation camps, stating that they were “clearly unconstitutional,” and that “the continued retention of these innocent people in the relocation centers would be a blot upon the history of this country.” Ickes elaborated on his position in 1946 after the war had ended:

As a member of President Roosevelt’s administration, I saw the United States Army give way to mass hysteria over the Japanese. . . . It began to round up indiscriminately the Japanese who had been born in Japan, as well as those born here. Crowded into cars like cattle, these hapless people were hurried away to hastily constructed and thoroughly inadequate concentration camps, with soldiers with nervous muskets on guard, in the great American desert. We gave the fancy name of “relocation centers” to these dust bowls, but they were concentration camps nonetheless.

It was not until 1988 when President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act that the Japanese American community was formally issued an apology and reparation payments of $20,000 were made to each surviving victim. More than 100,000 Americans of Japanese descent were interned during World War II. Internee Margaret Takahashi recalled her internment:

When I think back to the internment, I want to call it a concentration camp, but it wasn’t. We have a neighbor who escaped from Auschwitz during the war, and there’s no comparison. In our life it was only four months, and that’s not long. But the evacuation did change our philosophy. It made you feel that you knew what it was to die, to go somewhere you couldn’t take anything but what you had inside you. And so it strengthened you. I think from then on we were very strong. I don’t think anything could get us down now.

The complacency of the majority of the Japanese Americans in the face of such an affront to their civil liberties astounded most, but internee Akiko Mabuchi explained why she and other of her generation remained so passive in the face of internment. For her, it was not complacency they were displaying, but defiance:

Our generation was raised to never call attention to ourselves, to work twice as hard as others, and above all never to bring shame to the family. We had a strict upbringing. And women, in particular, were never to cause any waves in society. I think it was because our parents were having enough trouble at the time making their way in America and showing their loyalty, they didn’t want us to make it harder. So when the war broke out, the only thing we felt we could do was go behind that barbed wire to prove we were loyal. I lost three years of my life and my parents lost everything they had built up over the years. But I sure hope we proved it.

Shimomura still has 37 of the 56 diaries that his grandmother wrote, noting that she burned several of these from the wartime period. Like many Japanese Americans, Shimomura’s grandmother Toku burned many diaries in fear that American officials would misconstrue any sentimental references to her homeland as a sign of disloyalty. Some Japanese Americans were imprisoned simply for writing that they missed Japan.

Roger Shimomura has stressed that the most important thing to emphasize to students of history about the relocation camps is what happens when other factors supersede the constitutional rights guaranteed to all Americans citizens – and that the phenomena could happen again. The artist cited the Iran Hostage Crisis in 1979 and the events of September 11, 2001 as examples of when public discussions were held in America about interning Americans of Middle-Eastern descent.

Stereotypes and Popular Culture

American artists across time have turned to popular culture as a sign of the changing nature of contemporary life. They bring a unique perspective to this subject that is attuned to the vernacular traditions of urban, working-class communities. The two artists featured here examine objects of daily life, redefining imported traditions and iconographies in a new context, and often expanding notions of art making in the process. By actively mining the stuff of everyday life, they comment on the meaning of American popular culture.

Exactly how do contemporary artists like Mel Casas and Roger Shimomura address racial stereotypes in their artwork? How does popular culture influence this depiction? How does personal experience affect an artist’s artwork? How do artists portray contemporary social, racial, and other concerns in their artwork? Both Latino artist Casas and Shimomura, an American artist of Japanese descent, tackle these questions and issues in their respective paintings, Humanscape 62 and Diary: December 12, 1941.

Each of these artworks are part of a larger series. The use of a series by these artists is indicative of the broader discussion required to understand the issues raised in the paintings. Both Casas and Shimomura have determined that a series of artworks was needed to expand on the themes and concerns they broach in their artwork – the issues are simply too important and complex to be devoted to a single canvas.

The oversized canvases in Casas’ Humanscape series use symbolic images, magnified graphics, and text to comment on the divisions between races, genders, and cultures. When observing race, Casas often expresses his commentary in archetypes, exploring racism through the racist’s point of view. Shimomura’s “Diary” series expands on the artist’s personal reminiscences as an internee in a World War II-era Japanese internment camp. Combining Pop Art aesthetics with cartoon imagery, Shimomura’s series is based off of entries in the diary his grandmother Toku Shimomura kept while the family was interned at Camp Minidoka in Hunt, Idaho.

Humanscape 62

Casas’ Humanscape 62 crystallizes many of the recurring concerns featured in Chicano art of the late 1960s and 1970s. Painted in 1970, this artwork is part of Casas’ “Humanscape” series, each which feature a large central image that evokes a television or movie screen, populated with everyday life imagery. Casas recounts how he was inspired to create his large six-foot by eight-foot paintings mimic large, outdoor drive-in movie theater screens: “When I painted those six- by eight-footers, again it wasn’t that I decided, “Oh, I’m going to paint six- by eight-footers.” What happened was that I was imbued with the power of the outdoor theater-the movie theater-and the big screen. And in a sense I’m consciously I was mimicking that.”

The images explore the artist’s interest in psychology and popular media culture. Early “Humanscape” artworks explored how the media shapes our idea of beauty and desire – and the dominance of what Casas’ called the “Barbie Doll Ideal,” referencing the white female figure. Yet as his series developed, the issue of race began to take precedence in Casas’ work and, not coincidentally, this development corresponded with the advent of the Chicano Rights Movement in the 1960s. The movement came to prevalence in the American consciousness thanks to the tireless efforts of rights leader Cesar Chavez. Chicanos were active across a broad section of issues including farm workers’ rights, education, and voting and political rights. They also protested against the racial stereotypes portrayed in the media.

One of the first protest campaigns to take on a specific stereotypical image was the campaign to eradicate the Frito Bandito, the sombrero-toting stereotypical mascot for Frito-Lay corn chips featured on television commercials. Speaking broken English and robbing unsuspecting bystanders of their Frito’s corn chips, the Bandito character was drawn as a cartoon Mexican con man with a disheveled appearance and a gold tooth. The Bandito was also featured in several print ads which depicted the character on a wanted posters. The ad warns the consumer, “Caution: he loves crunchy Fritos corn ships so much he’ll stop at nothing to get yours. What’s more, he’s cunning, clever – and sneaky!” The ad also warns citizens to protect themselves. The ad clearly labels the Bandito as not only a dangerous immigrant, but it reinforces the commonly held stereotype about Mexicans that they are lazy – the Bandito prefers to steal, rather than work.

Casas’s Humanscape 62 was created during the debate over Frito Bandito. Casas recalled, “I felt the need to express something about what was going on.” In the painting, the artist has included an image of the Bandito in green in the center of the painting. Frito-Lay responded to public pressure and outrage by refining the Bandito’s appearance, grooming his hair and giving him a friendlier expression. The change did not sit well with the public and ultimately Frito-Lay replaced Bandito with a new series of cartoon characters.

The Bandito in Casas’ painting, as well as the other objects in the work, are all associated with brown culture, or share a connection to “brownness.” The term gained popularity in the 1960s and 1970s and increasingly signified Chicanos and their indigenous Meso-American ancestry. Casas has captured a group of trivialized snippets drawn from popular culture making “brown” references, including a junior Girl Scout (known as a Brownie), a jade mosaic sculpture of the Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl – the feathered serpent that extends the width of the lower register of the painting, a group of Mexican women, and a Native American in profile. Huge chocolate brownies occupy the majority of the top register, and are a nod to something both commonplace and historical. The popular cake-like brownies have their origin in Meso-America. Cacao beans, the source of chocolate, was a prized agricultural product of the Aztecs in the fourteenth century and could only be grown in the highlands of central Mexico. The section containing the brownies is slightly bowed at each end, an allusion to the first television screens which were similarly bowed. Casas has merged these references with those of indigenous culture to question the ways in which mainstream American popular culture has demeaned brown cultures, whether they be Mexican American or indigenous.

Casas’ personal experiences as a bilingual American also influenced his decision to tackle these issues in his artwork. The artist recalled:

I realized that we had a bicultural problem. Meaning some of us were from a “Hispanic origin.” Accidentally that’s the way it happens. Some were from “Anglo.” Both of them in quotation marks, whatever that means. And even though we all are Americans I found out I was less an American, and the reason I found out I was less an American is because I really spoke with an accent. Secondly, I was bilingual, and in America to be bilingual is to be suspect. We like to have all Americans speak only English.

Casas struggled with and raised the important issue of ethnic identity in art. As an American artist of Mexican heritage, but one who did not self-identify with the term Chicano, he wondered: were his paintings considered Chicano art because he was Chicano? Or was it the subject matter that made the art Chicano art? In an interview, the artist recalled, “You have here-in quotes-“Chicano artists,” “Chicano group,” so therefore they paint “Chicano art.” Well, what is Chicano art? Is it Chicano art because it’s an ethnicity thing? Or is it a subject thing? Those are the kind of questions I had that people didn’t want to deal with.”

Diary: December 12, 1941

Having survived and largely repressed the trauma of his family’s internment during World War II and a childhood spent in the racially insensitive environment characteristic of the United States in the 1950s, Roger Shimomura had learned to minimize his differences with mainstream white America. His discovery of a rich collection of family documents and memorabilia after the death of his grandparents inspired the artist to examine their lives as immigrants to the United States and, most importantly, the part of their lives he shared most intimately with them—the internment years at Camp Minidoka in Hunt, Idaho.

In keeping with mid-century American attitudes, Shimomura did not pursue formal training in the language or culture of his forebears. When he began to examine his grandmother’s extensive series of diaries—there were more than fifty years of diaries beginning with her arrival from Japan in 1912 and continuing until her death in 1968—he required the services of a translator. The diaries from the war years proved to be especially evocative, reviving early memories for Mrs. Shimomura’s grandson and inspiring in him both the desire to commemorate this reprehensible episode in our nation’s history, and to share its lessons with a new generation of Americans.

Between 1980 and 1983, Shimomura completed twenty-five paintings in the “Diary” series, each paired with a specific diary excerpt. Uniform in size and style, these paintings constitute a powerful collection of formally and emotionally compelling images. The flat, hard-edged forms and bright colors Shimomura uses to depict his shoji screens and kimonoed figures derive from his familiarity with ukiyo-e woodcuts and his admiration for the slick Pop Art images of artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Shimomura refers to this tendency as his “love of painting flat.”

The painting entitled Diary: December 12, 1941, based on an entry dated five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, is especially effective in suggesting the psychological dynamics of guilt, fear, and resignation involved in the Japanese-American dilemma created by that event. On December 12, 1941, Shimomura’s grandmother wrote in her diary: “I spent all day at home. Starting from today we were permitted to withdraw $100 from the bank. This was for our sustenance of life, we who are enemy to them. I deeply felt America’s largeheartedness in dealing with us.” Her words express only sadness and gratitude towards the American authorities. Such an attitude is in keeping with the stoic behavior of the Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrants. Shimomura uses the Japanese word giri, which means “hold it in and endure,” to describe their way of coping. But in the painting, he emphasizes a growing feeling of isolation and confinement, symbolized by the disposition of the converging screens that barely allows enough space for the figure.

The normally nonthreatening figure of pop culture icon Superman is transformed into a menacing shadow, looming over the figure of Shimomura’s grandmother. The inclusion of Superman is a reference to Shimomura’s love of comic books. The artist grew up in the 1940’s and 1950’s during the heyday of action comics and superheroes, avidly reading cartoons like Dick Tracy, Superman, and several Walt Disney comics and cartoons. The graphic tradition of comics employs the thick outlines and flat silhouettes Shimomura would later come to use in his artwork. Comic books are also stylistically similar to ukiyo-e prints; a connection Shimomura acknowledged once, saying, “I realized that the only difference between Minnie Mouse and [the women in ukiyo-e prints] was race.”

Despite Superman’s heroic persona in the comics, Shimomura interprets Superman in another way: “Superman is my response to the ‘large hearted American’,” a reference to his grandmother’s December 12th diary entry. Superman is not the all-American hero as he appears in the comics. In Shimomura’s artwork, he personifies a domineering American federal government, responsible for imprisoning nearly 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

The painting’s crisp, colorful forms contradict its serious content and message. In the 1985 catalogue for an exhibition of the “Diary” series, Shimomura commented on this contradictory character, noting:

The dichotomy between craft and subject [is probably] appropriate, like memory brought back into focus. . . . It has always been of paramount importance to me that my work, beyond anything else, have visual interest. [These] paintings . . . were the most exciting to work on because I have to deal with the relationship between political (literal) and visual issues; in this case maybe a little like putting perfume over body odor.

What lies beneath the surface of the canvas are serious issues of race, racism, assimilation, and the complex entanglement of issues one faces as an American of non-European descent.

Visual culture in contemporary art can be used to start discussions about how race and race relations are part of our daily lives. In particular, the artwork of contemporary artists of color asks viewers to consider the artist’s social position in relation to our history, which has been shaped by our own experiences. The artwork of Casas and Shimomura urge us to consider multiple American realities and perspectives.

Primary Source Connections

The Civilian Exclusion Order #5

The Civilian Exclusion Order #5

Courtesy of Densho, the Yamada Collection

The first official act of the relocation effort was to notify “all persons of Japanese ancestry” of the evacuation from the military zone along the west coast. Posters like this one were hung in specific neighborhoods throughout Washington, Oregon, and California. Expectations regarding the early phases of internment were clearly detailed. 108 orders were issued over a period of five months —from late March to August, 1942—systematically facilitating the removal of all Japanese Americans in California, Washington, Oregon, and parts of Arizona neighborhood by neighborhood.

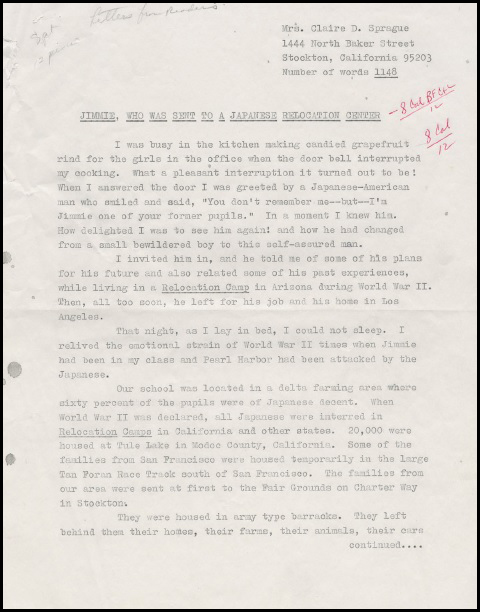

A letter from a teacher in Stockton, CA about her student “Jimmie,” who was sent to an internment camp, 1942

A letter from a teacher in Stockton, CA about her student “Jimmie,” who was sent to an internment camp, 1942

Read the letter at the Digital Public Library of America

In this primary source, a teacher from Stockton, California recalls her Japanese-American student Jimmie. She details what life was like for her students, for teachers, and what life was like in general during World War II. An excerpt is below.

Much too soon, our pupils left for their new temporary homes. I tried to reassure my pupils that before too long they’d be back with us again. While they were at the County Fair Grounds we teachers visited them regularly and brought them school books and assignments and a few “goodies” for treats. We often shopped for the parents. I always looked for Jimmie and reassured him that his dog was well cared for and happy in that big old barn that was now his dog’s home. After some months, these Japanese-American families were moved to more permanent quarters in California and in other states. I didn’t see any of my pupils again until World War II was over, but the children wrote me many letters.

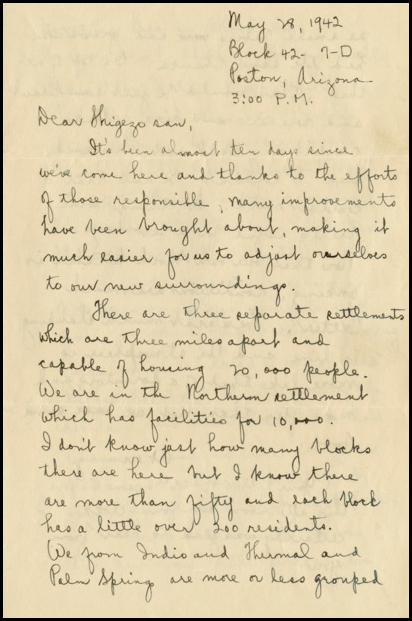

Letter from Sonoko U. Iwata to Shigezo Iwata, May 28, 1942

Letter from Sonoko U. Iwata to Shigezo Iwata, May 28, 1942

From the Selected Shigezo and Sonoko Iwata Correspondence, May 28-July 22, 1942; Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Excerpt: “It’s been almost ten days since we’ve come here and thanks to the efforts of those responsible, many improvements have been brought about, making it much easier for us to adjust ourselves to our new surroundings. There are three separate settlements which are three miles apart and capable of housing 20,000 people. We are in the Northern settlement which has facilities for 10,000. I don’t know just how many blocks there are here but I know there are more than fifty and each block has a little over 200 residents . . . each block is like one community and it’s up to those of us who comprise the community to make it better, through cooperative efforts.”

Literary Connections

Imprisoned Apart : The World War II Correspondence of an Issei Couple, 1997, Louis Fiset

Find it in a Library

“Imprisoned Apart is the poignant story of a young teacher and his bride who came to Seattle from Japan in 1919 so that he might study English language and literature, and who stayed to make a home. On the night of December 7, 1941, the FBI knocked at the Matsushitas’ door and took Iwao away, first to jail at the Seattle Immigration Stateion and then, by special train, windows sealed and guards at the doors, to Montana. He was considered an enemy alien, “potentially dangerous to public safety,” because of his Japanese birth and professional associations. The story of Iwao Matsushita’s determination to clear his name and be reunited with his wife, and of Hanaye Matsushita’s growing confusion and despair, unfolds in their correspondence, presented here in full. Their cards and letters, most written in Japanese, some in English when censors insisted, provided us with the first look at life inside Fort Missoula, one of the Justice Department’s wartime camp for enemy aliens.” – University of Washington Press

Memoir of Mary Paik Lee, 1990

Memoir of Mary Paik Lee, 1990

Find it in a Library (Excerpt from page 94)

“When the tragedy of Pearl Harbor struck, all the Japanese were forced to leave their homes and property and were taken to concentration camps. Our neighbors asked if we would look after their farms; they told us to take anything we wanted from their homes. They were our friends, so we couldn’t do that, but we said we would look after their things as much as possible. One friend asked us to live on his property, rent-free, to keep out strangers who might be coming around to take whatever they could. We told all of them that we would do our best. It was not a through road, so not too many people came by. After the Japanese left, however, many white people came in trucks, intending to take away all kinds of belongings. But when they saw us watching, they left. Many prominent Japanese were taken away quickly. We heard that many Japanese homes were looted, especially in the cities, but no one protested such actions. . . . The day of Pearl Harbor, we had left home very early and had worked all day in the field. We had no way of knowing what had occurred. After taking the workers home, around 7 P. M., I stopped by the Nixon’s grocery store to buy something. I left my one-year-old son, Tony, in the truck, thinking I’d be back in two minutes. I was surprised to see the room full of people who stared at me with hateful expressions. One man said, “There’s one of them damned Japs now. What’s she doing here?” Mrs. Hannah Nixon came over to me and said to her friends, “Shame on you, all of you. You have known Mrs. Lee for years. You know she’s not Japanese, and even if she were, she is not to blame for what happened at Pearl Harbor! This is the time to remember your religion and practice it.” What a wonderful, courageous woman to take such an unpopular stand for me, an Oriental, upon whom every white person was looking with hatred.”

Artwork Connections

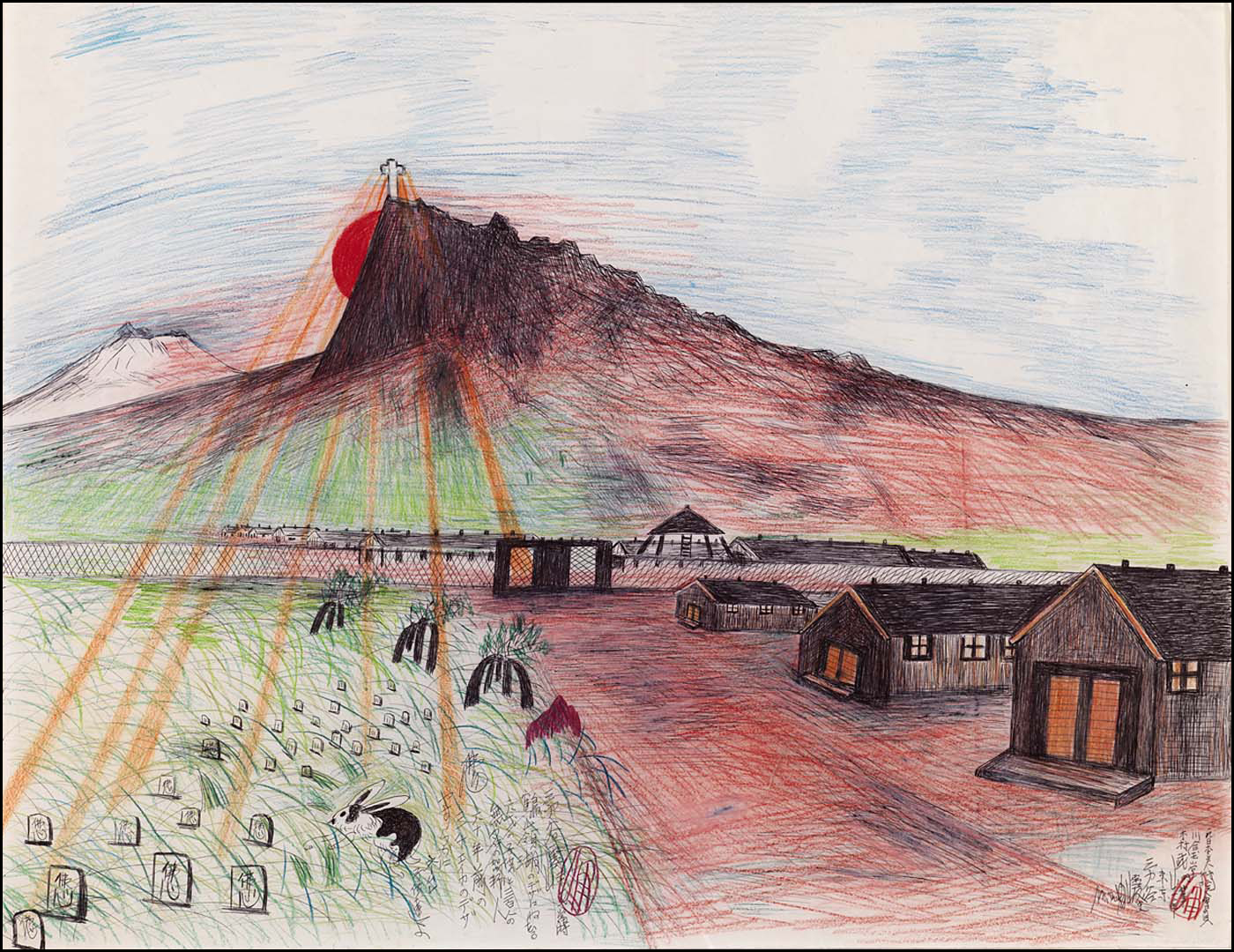

Cemetery, Tule Lake, 2002, Jimmy Tsutomu Mirikitani

Jimmy Tsutomu Mirikitani was among 120,000 Japanese-Americans wrongfully incarcerated by the U.S. government during World War II because of unfounded fears that they were a threat to national security. Mirikitani spent nearly four years at Tule Lake Relocation Center in Newell, California. From 1943 until the end of the war, the War Relocation Authority, the federal agency responsible for administering the internment facility transferred over 12,000 individuals from other camps to Tule Lake who were considered “disloyal.” Many of these individuals had refused to answer “yes” to two questions on a loyalty questionnaire asking them to volunteer for military service and to renounce any ties to Japan and other countries. Many like Jimmy were forced to renounce their U.S. citizenship, and over 1300 Japanese-Americans were expatriated to Japan.

The Farm, 1934, Kenjiro Nomura

The Farm, 1934, Kenjiro Nomura

Kenjiro Nomura painted The Farm under the auspices of the Public Works of Art Project during the Depression. Yet ironically and tragically, after being hired in 1933 by the PWAP to celebrate the American scene, Nomura, along with many other Japanese Americans, was forced into an internment camp during World War II. This injustice brought his career to an end until 1947, when he began exhibiting again

Black & White, 1993, Byron Kim and Glenn Ligon

This collaboration between artists Byron Kim and Glenn Ligon is a grouping of thirty-two small monochromatic paintings based on skin tones; sixteen versions of black skintone straight out of the paint tube and sixteen versions of white skintone straight out of the paint tube. Black & White exploits the notion of “flesh tone” as a color and the prejudices of art materials, specifically tubes of paint labelled “Flesh” to connote “white” or “tan” skintones.

Media

Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art – Melesio Casas (4 min)

In this series, E. Carmen Ramos, curator of Latino art, discusses the exhibition “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. This episode looks at the painting “Humanscape 62” by Melesio Casas.

Immigration to the United States since 1965 (50 min)

From The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

Smarthistory’s “Superman, World War II, and Japanese-American Experience”

“Approaching Research: Diary: December 12, 1941” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

Subject: History

Japanese American Exclusion Orders During WWII – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Japanese American Incarceration Era Collections – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

During WWII almost 120,000 Japanese Americans were uprooted from the West Coast regions that were deemed military exclusion zones, moved cities and states away, and controlled under severe restrictions. We can better understand the lives, experiences, and stories of these people by studying objects within the National Museum of American History’s collection.

A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans & the U.S. Constitution – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

This site explores a period of U.S. history when racial prejudice and fear upset the delicate balance between the rights of a citizen versus the power of the state. Focusing on the experiences of Japanese Americans who were placed in detention camps during World War II, this online exhibit is a case study in decision-making and citizen action under the U.S. Constitution.

Lesson Plans and Student Activities

The Japanese American Internment: How Young People Saw It – Smithsonian Education

Through primary and secondary sources, students learn of the experiences of children and teens in World War II internment camps. This set of four lessons is divided into grades K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12

Letters from the Japanese American Internment – Smithsonian Education

The Japanese American National Museum, a Smithsonian affiliate in Los Angeles, presents personal accounts of the internment in an online exhibition, Dear Miss Breed: Letters from Camp. Here we use four of the Miss Breed letters in a lesson plan on the study of letters as primary source documents. As students compare the writers’ differing points of view, they might see more clearly that the history of an event or period of time is never a single story.

Our Story: Life in a WWII Japanese American Internment Camp – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Glossary

1924 Immigration Act: also known as the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924; the act limited the number of immigrants from any country to 2% of the number of people from that country who were living in the United States at the time of the 1890 census.

Andy Warhol: (1928-1987) American artist and filmmaker. He was a leading figure of the Pop Art movement, and is best known for his work exploring celebrity and consumer culture.

Asian Exclusion Act of 1924: also known as the 1924 Immigration Act; the act limited the number of immigrants from any country to 2% of the number of people from that country who were living in the United States at the time of the 1890 census.

attack on Pearl Harbor: a surprise airstrike by the Japanese on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941, which led directly to the United States’ entry into World War II.

brown: a term used to denote a racial or ethnic classification. Generally, it is used to describe people with “brown” skin tone who are of Hispanic or native ancestry.

Camp Minidoka: one of ten internment camps Americans of Japanese descent were sent to after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Camp Minidoka, located in Hunt, Idaho, was the camp to which artist Roger Shimomura and his family were assigned.

Cesar Chavez: (1927-1993) union leader and labor organizer. Founder of the NFWA (later the UFW), Chavez advocated for farm workers’ rights and employed Gandhi’s tradition of peaceful, non-violent social change.

Civil Liberties Act: the 1988 act signed by President Ronald Reagan which granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been interned by the United States government during World War II.

Chicano: a chosen identity of an American of Mexican origin or descent. The term came to prominence during the Chicano Rights Movement. Some members of the community view the term with negative connotations, as it was used previously in a derogatory manner.

Chicano Rights Movement: a period of widespread social and political activism within the Mexican American community during the 1960s and 1970s.

Executive Order 9066: signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the order designated certain areas as military zones and authorized the evacuation of all persons deemed a threat to national security to those zones. While not explicitly stated, the order essentially authorized the internment of nearly 120,000 people of Japanese descent during World War II.

Iran Hostage Crisis: a diplomatic crisis between Iran and the United States, where more than sixty Americans were held hostage in Iran for 444 days (from November 4, 1979 to January 20, 1981).

Issei: a Japanese term meaning “first generation.” Used to describe the first Japanese to immigrate to the United States.

Meso-American: (or Mesoamerican) of or relating to the people of Mesoamerica or their languages or cultures. Mesoamerica was the region and cultural area of the Americas during the pre-Columbian era (pre-1492) which extended from central Mexico to Honduras and Nicaragua.

Naturalization Act of 1906: signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt, the act limited racial eligibility for citizenship. It also required citizens to learn the English language in order to become naturalized.

Nisei: a Japanese term meaning “second generation.” Used to describe the U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants.

No-No Boys: the colloquial term for detained Japanese Americans who answered “no” to questions 27 and 28 on the so-called “loyalty questionnaire” during World War II. Those who answered no, or who were deemed disloyal, were segregated from other detainees and moved to the Tule Lake Relocation Camp in California.

Pop Art: a style of art based on modern popular culture and the mass media, especially as a critical or ironic comment on traditional fine art values. The Pop Art movement began in the 1950s, reaching its peak in the 1960s. Major artists of the movement include Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

pop culture: short for “popular culture,” the term describes cultural activities or commercial products reflecting, suited to, or aimed at the tastes of the general mass populous.

Ronald Reagan: 40th President of the United States.

reparation: the act or process of making amends for a wrong or injury, often involves monetary compensation.

September 11, 2001: on this day, a series of four coordinated terrorist attacks took place by the Islamic terrorist group Al-Qaeda, targeting symbolic American landmarks.

ukiyo-e: a Japanese genre of art depicting subjects from everyday life, which flourished from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

War Relocation Authority: the government agency in charge of the management of the ten relocation camps that Japanese American were sent to during World War II.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards

Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968-the present)

Standard 2B – The student understands the new immigration and demographic shifts.

- 5-12 – Analyze the new immigration policies after 1965 and the push-pull factors that prompted a new wave of immigrants.

- 9-12 – Identify the major issues that affected immigrants and explain the conflicts these issues engendered.

- 7-12 – Explore the continuing population flow from cities to suburbs, the internal migrations from the “Rustbelt” to the “Sunbelt,” and the social and political effects of these changes.

Standard 2D – The student understands contemporary American culture.

- 9-12 – Analyze how social change and renewed ethnic diversity has affected artistic expression and popular culture.

- 7-12 – Explain the influence of media on contemporary American culture.

Standard 2E – The student understands contemporary American culture.

- 7-12 – Evaluate the continuing grievances of racial and ethnic minorities and their recurrent reference to the nation’s charter documents.

- 9-12 – Evaluate the continuing struggle for e pluribus unum amid debates over national vs. group identity, group rights vs. individual rights, multiculturalism, and bilingual education.

Historical Thinking Standards

The preceding information supports the following Historical Thinking-based concepts:

Standard 1. Chronological Thinking

- Distinguish between past, present, and future time.

Standard 2. Historical Comprehension

- Identify the author or source of the historical document or narrative.

- Reconstruct the literal meaning of a historical passage.

- Differentiate between historical facts and historical interpretations,

- Appreciate historical perspectives.

- Draw upon the visual, literary, and musical sources.

Standard 3. Historical Analysis and Interpretation

- Consider multiple perspectives.

- Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues.

Standard 4. Historical Research Capabilities

- Formulate historical questions.

- Obtain historical data.

- Interrogate historical data.

- Support interpretations with historical evidence.

- Identify issues and problems in the past.

- Identify relevant historical antecedents.