After the Civil War, the country was eager to heal itself from the divisive wounds inflicted after five years of bloodshed. Americans looked back to the Revolutionary era and to its leaders for inspiration and ideals on which to model to the newly unified country. From the Declaration of Independence through Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown in 1781, the political and military missions were inextricable – to make amateur soldiers competent to fight a highly professional British imperial army, to convince them that they were fighting for themselves, and to help them be good citizens of an idealistic republic. George Washington understood his symbolic value was nearly as important as his military successes. He exemplified the ideals of freedom and equality advanced in the Declaration, maintaining throughout the War of Independence that he and the army served at the pleasure of Congress, who had entrusted him and the army with “the maintenance and preservation of American liberties. The sculpture of George Washington resigning his military commission was created at a time when political power was being consolidated around the federal government. The sculpture was intended as a reminder of the nation’s founding ideals and principles, and also of the resignation of Washington; the act of which acknowledged the dangers of too much power in the hands of too few. Likewise, America’s centennial in 1876 provided the prefect opportunity to celebrate these ideals and renew goals and aspirations for the nation. Daniel Chester French’s sculpture of a Revolutionary Minute Man leaving his plow to pick up his gun to fight for independence serves as a reminder of America’s declaration of independence and of its founding principles.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Artist make choices in communicating ideas. These two artworks were created many years after the respective events that they depict. Why would the artists choose to commemorate these events when they did? What are the Minute Man and George Washington’s significance to the nation nearly one hundred years after the Revolutionary War? What clues do the artists give us to answer this question? Observing details and analyzing components of the sculptures, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of these artworks

Observation: What do you see?

What does Washington hold in his right hand?

In his outstretched hand, Washington holds a rolled up piece of paper. From the title of the artwork, we can infer that this piece of paper is his military commission of the Continental Army. He hands over his commission papers, formally resigning his position as General of the Army.

Describe Washington’s attire and his stance? Taken together, what do these two elements convey about Washington?

Washington is dressed in the military regalia of the Continental Army, similar to a 1789 uniform of his on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. He wears a uniform coat, which would have been dark blue in color, with gilt buttons. The coat is adorned with epaulets on the shoulders made of braided gold thread, indicating his military rank. He wears a beige wool waistcoat with matching knee breeches and knee-high leather boots. His white undershirt reveals a ruffled collar and ruffled sleeve cuffs. Washington’s pose reveals confidence without arrogance. He stands in contrapposto, a pose where most of his weight is on one side so that his upper torso and shoulders are twisted off-axis from his hips and legs. His left hand rests on the hilt of his sheathed sword as he calmly extends his right arm, offering his resignation. His facial expression is resilient and steadfast, confident in his decision that his resignation is in the best interests for the young nation.

Perhaps the most dramatic part of Washington’s ensemble is his floor-length cape. The cape serves to add drama to an otherwise static artwork, but also adds supportive structure to the large sculpture. This convention of placing a structural support under the guise of a compositional element harkens back to ancient Greek and Roman marble statuary. Marble did not have the proper tensile strength to bear its own weight so artists would add supports, called struts, in order to achieve the necessary balance of weight. These supports were often modeled in the forms of tree trunks. The material of this artwork is plaster painted to look like bronze, but it was thought that it would eventually be transferred to marble or bronze, in which case extra support would have been necessary for the structural integrity of the artwork.

What do the plow and the rifle tell us about the minuteman?

The Minute Man holds the handle of a plow in his left hand, an essential tool for his occupation as a farmer. The plow draws attention to the land itself, representing the physical territory that the man hopes to defend from British aggression. His right hand grips a musket, showing that he is ready to fight for the American colonies – not yet a country – at a moment’s notice. In contrast to the plow, the musket is a symbol of war. Here, the farmer turns away from the peaceful act of farming to take up his weapon as a soldier.

How is the Minute Man posed? What do you sense he will do next?

The Minute Man stands resolutely with one foot forward, as though in mid-stride. This is not an introspective moment – he has already made the decision to fight and is walking forward, ready for battle. His determined step is echoed in his squared shoulders and steady gaze. Daniel Chester French chose to base the figure’s pose on the Apollo Belvedere, a celebrated classical sculpture from Roman antiquity that first exhibited this stance of impending motion. Imagine the minuteman as a static figure standing firmly on both feet. How would it change the tone or energy of the figure?

Interpretation: What does it mean?

When paired together, these two artworks represent bookends of the American Revolution. The first, the minuteman, represents the beginning of the Revolution – a patriot setting aside his farming implements to answer the call to arms. George Washington, depicted in the act of resigning his military commission, represents the conclusion of the Revolution. In resigning his commission, he lays down his sword in order to return to life as a gentleman farmer now that the need to have a standing army has passed. Washington declared that “as the sword was the last resort for the preservation of our liberties, so it ought to be the first thing laid aside, when those liberties are firmly established.” He believed that only monarchies needed standing armies, chiefly to keep citizens subdued. Citizen militias like the minutemen were organized at moments of crisis and quickly disbanded, representing the true nature of a democracy. The men who comprised these militias came from many professions and spent only a portion of their time at arms. Called “minutemen” for their ability to be armed and ready at a minute’s notice, they were the adversarial force against the British in the first two military altercations of the Revolutionary War, the battles of Lexington and Concord.

Ferdinand Pettrich created the sculpture of George Washington in 1841 at a time when political power in the United States was being consolidated around the federal government. He may have felt that this historic moment in Washington’s life would remind a new generation of the nation’s founding ideals, and of the dangers of too much power given to too few. Similarly, Daniel Chester French was commissioned in 1871 to create a larger-than-life sculpture of a minuteman to commemorate the centennial of the battle at Concord in 1775 – the first altercation of the Revolutionary War where both sides fired shots. Ten decommissioned brass cannons from the Civil War were used to cast the mammoth sculpture, located on the site of the battle. This version in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum is a scaled-down version of the original, created at a later date in 1917.

The creation of the sculpture after the Civil War is significant as well. As a torn nation began to heal during Reconstruction, the figure of the Minute Man harkens back to a time when thirteen colonies banded together, united in their efforts against the British – a reminder that our nation is stronger together and will be again.

Historical Background

About the Artwork: Washington Resigning His Commission

In 1835 a movement was started in Philadelphia to erect a statue of George Washington in Washington Square. The foundation for the monument was laid but soon, the project began to languish. By 1840 there was enough money in the fund to resume plans for the monument’s execution, German artist Ferdinand Pettrich was the favored sculptor. On July 2, 1840, at a meeting of citizens of Philadelphia, a series of resolutions was adopted, one of which stated: “Resolved, that this meeting having been furnished with the best testimonials of the skill and classical taste of Ferdinand Pettrich, pupil of Thorvaldsen, that he be requested, at the earliest period, to furnish this committee a model of the statue upon a pedestal of proportionate dimensions, containing appropriate bas relief representations in full costume of the continental army of the revolution.” Sometime in August of 1840, an announcement was made that permission had been obtained from the Council of the City to exhibit the model of the Washington statue in Independence Hall, and that it would be on view there from August 18 until September 1. A description of the work was written in the August 29, 1840 issue of the Saturday Evening Post:

Statue of Washington. The model exhibited during the last week to large crowds in the Hall of Independence is one eighth of the full dimensions when completed. The bas reliefs on the four panels represent figures which are to be the size of life. The basement and sub-basement are to be composed of New England granite to the height of fourteen feet, and executed in imitation of rock work. The steps of which there are thirteen corresponding to the original confederation of the states are to be composed of Pennsylvania marble eight feet in height. The equestrian statue is to be eighteen feet in height, that is, from the hoofs of the horse, to the crown of the head of the rider and to be executed in iron made from anthracite coal from the mines of Pennsylvania. The model of the statue is made by Ferdinand Pettrich, sculptor. The pedestal and steps are designed by W. Strickland, architect. There are four panels with figures in bas relief representing – The surrender of Cornwallis. The Ladies of Trenton greeting General Washington and strewing his path with flowers from a triumphal arch erected on a bridge crossing Assunpink Creek. The occurrence took place twelve years after the battle of Trenton and on the same spot. The arms of the United States and military trophies. The surrender of his commission to Congress. All the bas reliefs to be cast in iron, and to be finished in what is called gunbarrel or brown bronze. The horizontal dimensions of the pedestal equal twenty-one feet by thirty feet and the whole height from the ground to the crown of the statue will be forty feet and the weight of the casting from twelve to fourteen tons. The whole estimate of cost will exceed fifty thousand dollars and may be completed in less than three years.

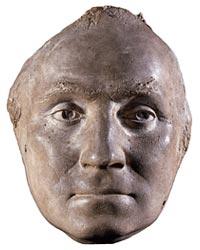

George Washington Life Mask, 1785, Jean-Antoine Houdon, plaster, Morgan Library and Museum.

By the time the public next heard of the planned monument, plans had significantly changed. The May 22, 1841 issue of the Saturday Courier stated that the subscribers to the “long contemplated statue of Washington” had decided to erect a “pedestrian statue to be wrought by the gifted Pettrich at a cost of ten thousand dollars.” A committee consisting of William Strickland, Joseph Hopkinson, and Thomas Sully was to oversee the work. The author of the article wrote that he had seen the plaster model for this pedestrian statue in Pettrich’s studio in the Merchant’s Exchange in Philadelphia. “It is truly a noble figure, simple and beautiful. The features are copied from and original cast of the face of the great and good man.” The cast referred to was the famous Houdon Washington life mask, which was given to Pettrich in 1839. Author R.H. Stehle hypothesized that this model seen by the writer may have been a free standing version of one of the panels mentioned for the pedestal of the equestrian statue. This model was most likely SAAM’s bronzed plaster statue of Washington Resigning His Commission, which was mentioned as having been the subject of one of the panels in the equestrian monument.

Primary Source Connections

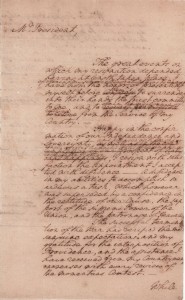

George Washington’s resignation speech to Congress on his appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army; December 23, 1783

George Washington’s resignation speech to Congress on his appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army; December 23, 1783

See the Document and Read the full transcript at the Maryland State House

“I consider it an indispensable duty to close this last solemn act of my Official life, by commending the Interests of our dearest Country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the superintendance of them, to his holy keeping.–

Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action, — and bidding an affectionate farewell to this August body, under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my Commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.”

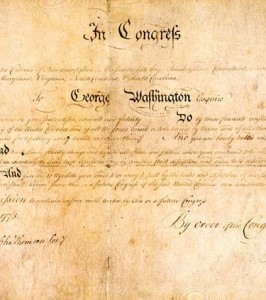

Washington’s Commission as Commander in Chief of the American Army, June 19, 1775

Washington’s Commission as Commander in Chief of the American Army, June 19, 1775

View the document at the Library of Congress

“On June 19, 1775, two days after the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Continental Congress selected George Washington (1732-1799) to lead the Continental Army. His commission, seen here, named him”Commander in Chief of the army of the United Colonies and of all the forces raised or to be raised by them and of all others who shall voluntarily offer their services and join the said army.”” – Library of Congress

Literary Connections

“Concord Hymn” 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Concord Hymn” 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Read the poem at Poets.org

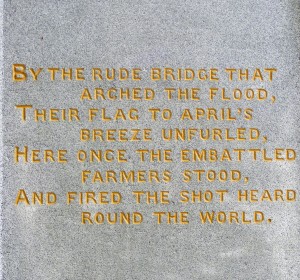

American writer/ philosopher Emerson wrote this poem for the dedication of the obelisk-shaped monument commemorating the Battle of Concord. Controversy ensued when some citizens cried foul that the monument was placed on the side of Concord Bridge where the British began the battle, and not where the Americans had stood. A second monument, French’s 1875 Minute Man sculpture, was commissioned for the opposite side of the bridge (timed for the Centennial celebrations). The first stanza of Emerson’s poem was engraved at the base of the Minute Man monument (detail at left). The poem is also referred to by its full title, “Hymn: Sung at the Completion of the Concord Monument, April 19, 1836.”

Artwork Connections

Liberty, ca. 1884, Frederic Auguste Bartholdi

Liberty, ca. 1884, Frederic Auguste Bartholdi

The Statue of Liberty was a gift from France to commemorate the centennial of the Declaration of Independence, and tp honor of the friendship forged between these countries during the American Revolution. Bartholdi brought this small-scale version of his monumental sculpture to Washington, where it was on view in the Capitol rotunda from 1884 until 1887. The figure holds a tablet bearing the inscription “July 4, 1776,” the date of American independence. A broken chain at her feet, she became an icon of freedom for the millions of immigrants who sailed past her on their way to Ellis Island.

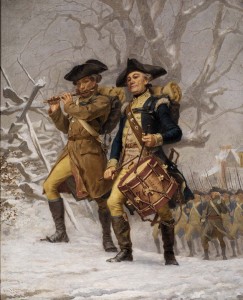

The Continentals, 1875, Frank Blackwell Mayer

Painted in 1875, this artwork was created for the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition held the following year. It depicts Continental Army soldiers on their way to that battle, marching through the snow to the beat of a drum and the sound of a flute. The soldiers march toward the battlefield of what would be the Battle of Bunker Hill, just outside of Boston.

Media

Washington as a Symbol of the Founding Era (2 min) From The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Washington’s Most Significant Act (2 min) From The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Subject: Art

George Washington: A National Treasure – Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

This resource celebrates our nation’s first president – the man, the icon, the hero. Through Gilbert Stuart’s original portrait of George Washington, students will be able to experience the most importance visual document of our nation’s founding.

“Approaching Research: Concord Minute Man of 1775” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

Glossary

bas relief: a sculpture which is carved so that the carved shapes project only slightly from the flat background.

Canova’s statue of Washington: Famed Italian sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822) was commissioned in 1816 for a sculpture of Washington for the North Carolina State House in 1816. Many who had recommended that the sculpture be put on rollers in case of emergency were proved correct, when a fire completely destroyed both the sculpture and the State House in 1831.

Equestrian: a sculpture of a rider seated on a horse. This type of sculpture has traditionally been reserved for military commanders.

Executive Mansion: one of the original names for the White House. The name was used until 1901, when President Theodore Roosevelt authorized the use of the name “White House.” Before the term “Executive Mansion,” the house was referred to as the “President’s House.”

Joseph Hopkinson: (1770-1842) member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. He served for many years as the president of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Horatio Greenough: (1805-1852) American sculptor who worked almost exclusively for the United States government. He is best known for his controversial sculpture of a toga-clad George Washington, based on a statue of the Greek god Zeus by ancient Greek sculptor Phidias.

Merchant’s Exchange: a brokerage house in the nineteenth century, designed in the Neo-Classical style by architect William Strickland, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Thomas Sully: (1783-1872) American portrait painter born in England, but who spent the vast majority of his life in the United States, specifically Philadelphia.

Thorvaldsen: Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844) internationally renowned Danish sculptor.

William Strickland: (1788-1854) American architect based in Philadelphia.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 3 – Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Standard 1C

-

- – The student understands the factors affecting the course of the war and contributing to the American victory.

- 5-12 – Appraise George Washington’s military and political leadership in conducting the Revolutionary War.

Historical Thinking Standards

The preceding information supports the following Historical Thinking-based concepts:

Standard 1. Chronological Thinking

- Distinguish between past, present, and future time.

Standard 2. Historical Comprehension

- Identify the author or source of the historical document or narrative.

- Reconstruct the literal meaning of a historical passage.

- Differentiate between historical facts and historical interpretations,

- Appreciate historical perspectives.

- Draw upon the visual, literary, and musical sources.

Standard 3. Historical Analysis and Interpretation

- Consider multiple perspectives.

- Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues.

Standard 4. Historical Research Capabilities

- Formulate historical questions.

- Obtain historical data.

- Interrogate historical data.

- Support interpretations with historical evidence.

- Identify issues and problems in the past.

- Identify relevant historical antecedents.