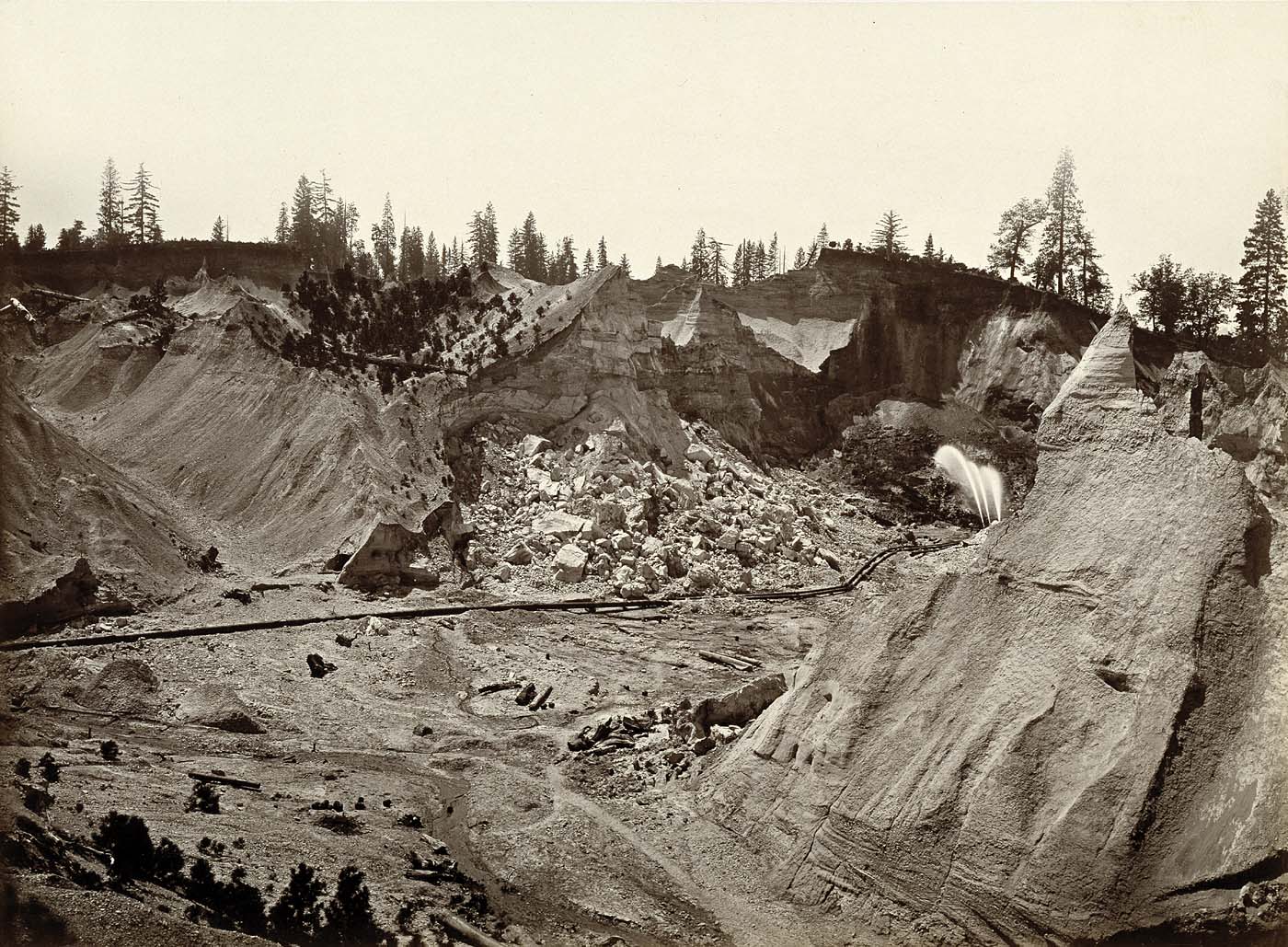

The discovery of gold in California prompted a wave of treasure hunters to pack up and head out west to try and seek out their fortunes. Charles Christian Nahl and August Wenderoth’s painting depicts a nostalgic view of panning for gold set in a lush, idyllic landscape. However, the reality for many of the miners was that they would never find gold. The realistic representation of the almost barren, primarily rocky terrain of Carleton Watkins’ photograph presents a stark contrast to the painting, providing the viewer with an inherently more accurate portrayal of what awaited miners out West. The photograph also introduces us to the new technology of hydraulic mining, a more effective method of mining than the more primitive method of panning for gold.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Westward expansion is one of the best-known episodes in American history. During the nineteenth century, many artists depicted the American West in a way that is still often treated as an objective account of national expansion. By looking closely at Miners in the Sierras and incorporating some historical context, we can discover that the art of the West often imaginatively invented its subjects instead of simply copying them. What story does this artwork tell? How does it reflect American values of the late 1800s?

Observation: What do you see?

Your eye is likely drawn to the bottom left corner of this large canvas first, toward the hub of activity in an otherwise peaceful landscape. Four men, their sleeves rolled up over muscled forearms, work together in the bright sun. At the far left, the man in a red shirt and broad-brimmed hat shovels earth into a long trough. The handle of his shovel acts as an arrow pointing to another man, also in a red shirt, wielding a pickaxe. Again, following the angle of the handle, the eye travels upward to a man in a blue shirt open to his navel who has raised a bucket to his lips. Finally, completing the zig-zag, the eye travels down to the right along the handle of another shovel. A man in a white shirt drops dirt into the trough.

Your eye is likely drawn to the bottom left corner of this large canvas first, toward the hub of activity in an otherwise peaceful landscape. Four men, their sleeves rolled up over muscled forearms, work together in the bright sun. At the far left, the man in a red shirt and broad-brimmed hat shovels earth into a long trough. The handle of his shovel acts as an arrow pointing to another man, also in a red shirt, wielding a pickaxe. Again, following the angle of the handle, the eye travels upward to a man in a blue shirt open to his navel who has raised a bucket to his lips. Finally, completing the zig-zag, the eye travels down to the right along the handle of another shovel. A man in a white shirt drops dirt into the trough.

In the background along the rocky outcroppings in the upper right section of the painting is a small brown cabin with a sunny, cleared yard and steps running down toward the miners. Smoke puffs from the chimney and laundry matching the red, white, and blue shirts of the toiling men hangs on the line outside of the home. Consider that the shirts are red, white, and blue. Of all of the colors available to them, Nahl and Wenderoth chose the colors of the American flag, linking this artwork and California to the Union.

Following the steps down to the river, the eye is taken along a smooth, slow-moving stream that cascades down three steps before being diverted back toward the men. Completing an oval path, the eye is drawn-along with the water-through the trough. The trough is long and narrow, balanced on the rocks around it. Red and yellow petals with verdant leaves peek out of grassy crags in the soft and curving boulders. A brilliant blue sky spreads across the top of the scene, lending its color to the mountainside in the distance. Soft, white clouds dot the sky.

Consider now how you would cut the painting into four parts. Nahl and Wenderoth have chosen to arrange their scene within an X-shaped composition. Implied lines running along boulders’ edges, following the lean of the topmost figures and skimming along the outcropping at the top right form one stroke of the X. The other stroke follows the outcropping at the left side, slips along the stream’s path, and joins the clearing on the far side.

Consider now how you would cut the painting into four parts. Nahl and Wenderoth have chosen to arrange their scene within an X-shaped composition. Implied lines running along boulders’ edges, following the lean of the topmost figures and skimming along the outcropping at the top right form one stroke of the X. The other stroke follows the outcropping at the left side, slips along the stream’s path, and joins the clearing on the far side.

Nahl and Wenderoth present the viewer with a pristine landscape near a stream in California. Despite the huge amount of canvas occupied by nature, our eye is driven back to the men and their work. Each man exhibits one step in the process of mining for gold. These men stand for the natural resources at American’s fingertips: keys to a booming economy.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

This scene of an unspoiled landscape readily giving up its wealth is certainly an invention. In the two years after gold was discovered near Sacramento, California in 1848, 80,000 people had moved west in search of treasure. President Polk encouraged Americans to settle the new state, and San Francisco quickly grew to be the fourth-busiest port in the nation.Artists Charles Christian Nahl and August Wenderoth were refugees from Germany’s political troubles of 1848. Like thousands before them, they came to California to find their fortunes. A single dwelling would, in reality, have been unlikely. In fact, most miners lived in camps so unsanitary that disease took many of these hopeful people’s lives.

Another clue that something is amiss is in the tools that these miners are using. Nahl and Wenderoth depicted four miners using a device called a long-tom to sift gold from rock and sediment in a Sierra stream, possibly Deer Creek. Yet as more people arrived and panned for easy-to-access surface deposits, prospectors had to work harder and dig deeper, often investing in more specialized equipment. Dozens of people – including people of Chinese, African and Mexican descent – would be required to do this dirty job. Panning for gold disappeared with the arrival of huge mining companies, making the newly-minted state of California an economic powerhouse.

Nahl himself had tried his hand at gold mining. In 1851 he purchased a claim in Rough & Ready, California – a crime-ridden, lawless town which lived up to its name. He and his family settled in an abandoned cabin and commenced to mine. Their meager earnings were supplemented by their mother’s doing laundry for camp residents, cooking, and selling some of the provisions that they brought with them. They abandoned camp not a year later.

Despite the negative experience, Nahl and Wenderoth depict a rosy view of this often fraught endeavor. This optimistic view of the gold rush experience is consistent with the American ethos at the time: that America would continue to be the land of opportunity for those willing to work hard enough.

Historical Background

The Gold Rush and Westward Expansion

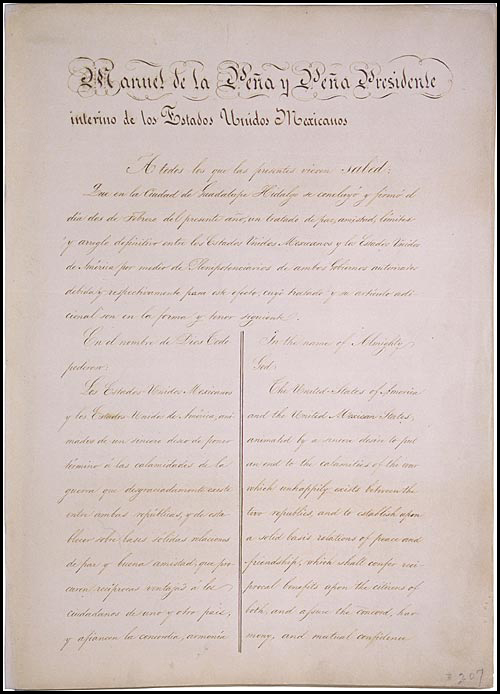

In order to understand the significance of the Gold Rush, it is important to look back at the events that led to the discovery of gold in California. One of the most important events was the Mexican-American War (1846-48). The Mexican-American War was a war of national aggression to gain territory. It followed the 1845 annexation of Texas, which Mexico regarded as its territory. In 1836 the Texian Army won the Battle of San Jacinto against Mexican forces, led by famed general Santa Anna, and the Republic of Texas declared its independence from Mexico. But Mexico had refused to acknowledge this action and warned the U.S. that if it tried to make Texas part of the U.S., Mexico would declare war. In 1845 Texas voluntarily asked to join the U.S., and became the 28th state. This action led to Mexico to declare war on the United States, starting the Mexican-American War.

U.S. Territorial Acquisition map courtesy of nationalatlas.gov

After a series of conflicts spanning two years, the United States won the war. When the dust settled, the U.S. had gained a significant amount of new territory. The region collectively known as the Mexican Cession included all of present-day California, Texas, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah. The signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo officially ended the war on February 2, 1848. In addition to the ceded territory, Mexico gave up its claims on Texas and recognized the Rio Grande River as America’s southern border.

At the time, the war was regarded as a major American victory over a hostile foe, but in the wake of the sectional strife of the Civil War the Mexican-American War was all but forgotten by history. But the war was pivotal in shaping our nation’s future. It cemented the idea of the United States as an expansionist, transcontinental empire. It fulfilled the nation’s vision of Manifest Destiny – creating one nation from Atlantic to Pacific. It shaped the land on which many Americans live today. And it led directly to the California Gold Rush.

The Discovery of Gold

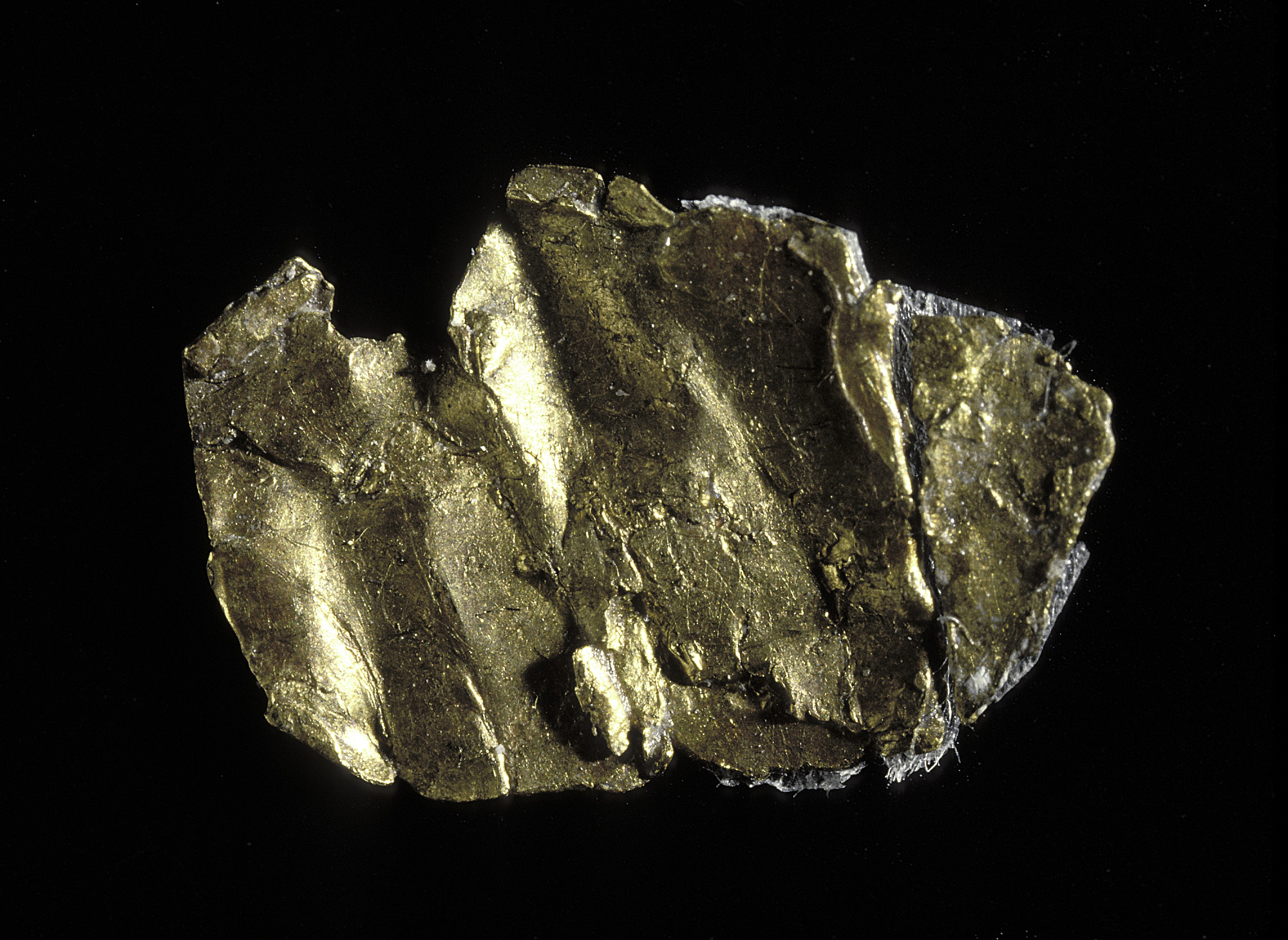

Unbeknownst to both the United States and Mexico at the time, the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo would serve to further America’s growing wealth and prestige. For just six days before the treaty was signed, gold was discovered in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California. None of the delegates at the signing of the treaty could have imagined that the rivers and streams in California were soon to yield a fortune in gold. In reality, neither the United States nor Mexico thought much of California. The land in California was a dangerous, semi-arid wilderness, inhabited with native tribes. The war had simply been about borders and territory – not what the territory actually held. Pioneers and migrants were more likely to choose the fertile territory of Oregon than they were California.

Gold was discovered on January 24, 1848 by John W. Marshall, a carpenter and sawmill operator who worked at Sutter’s Mill, owned by pioneer and German-born immigrant John Sutter. During his early morning routine check of the water-powered sawmill, Marshall spotted a glint of gold beneath the surface of the South Fork American River. Marshall plucked the pea-sized particle from the water and recalled, “I reached my hand down and picked it up; it made my heart thump, for I was certain it was gold.” Marshall took his discovery to Sutter, who used an encyclopedia to confirm the find. Sutter recalled the even years later in a magazine:

It was a rainy afternoon when Mr. Marshall arrived at my office in the Fort, very wet. . . . He told me then that he had some important and interesting news which he wished to communicate secretly to me, and wished me to go with him to a place where we should not be disturbed, and where no listeners could come and hear what we had to say. I went with him to my private rooms . . . I forgot to lock the doors, and it happened that the door was opened by the clerk just at the moment when Marshall took a rag from his pocket, showing me the yellow metal; he had about two ounces of it. . . . After [reading] the long article “gold” in the Encyclopedia Americana, I declared this to be gold of the finest quality, of at least 23 carats.

Sutter swore his workers to secrecy, but within months the secret was out, and the Gold Rush was on. Newspaper reports on the discovery were initially met with disbelief, but once evidence of gold was brought into San Francisco the frenzy began. The San Francisco-based journal, The Californian, published the following on May 29, 1848:

The whole country from San Francisco to Los Angeles, and from the sea shore to the base of the Sierra Nevada, resounds with the sordid cry of gold! GOLD!! GOLD!!! – while the field is left half planted, the house half built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pickaxes.

By mid-June 1848, three-quarters of San Francisco’s male population had left the city for the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in search of gold. All of Sutter’s workmen abandoned him to seek their fortunes in the rivers and streams, gripped with “gold fever Sutter complained that “even my cook has left me.” The Gold Rush turned life upside down.” When the news of gold reached the East coast, many men who had trained as bankers, lawyers, and doctors in the East now migrated westward, spending their days knee-deep in freezing water, moving rocks and stones until their hands were numb searching for gold.

This small piece of yellow metal is believed to be the first piece of gold discovered in 1848 at Sutter’s. Smithsonian Museum of American History

One man likened the “gold fever” to a highly contagious disease. Writing to his friends on the East coast he said, “The whole population are going crazy . . . Old as well as young are daily falling victim to the gold fever.” Wives and families were abandoned, left behind to figure out ways to support themselves. Shops were boarded up. Schools were closed. Soldiers abandoned their posts. Benjamin Kloozer, a soldier stationed in California, was torn between duty to his country and the lure of gold. As a soldier his wages were six dollars a month, but mining for gold he stood to make as much as $150 per day. Writing to his brother in Boston, he detailed his predicament, “I hate to desert . . . I am almost crazy. . . . Excuse this letter, as I have the ‘gold fever’ shockingly bad.”

Not all Americans viewed the Gold Rush as a positive occurrence for the country. Literary greats Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau spoke out on the detrimental effects of the event. Emerson wrote, “It was a rush and a scramble or needy adventurers, and, in the western country, a general jail-delivery of all the rowdies of the rivers.” Thoreau went further in his denunciation of the gold seekers, writing:

The recent rush to California and the attitude of the world, even or its philosophers and prophets, in relation to it appears to me to reflect the greatest disgrace on mankind. That so many are ready to get their living by the lottery of gold-digging without contributing any value to society, and that the great majority who stay at home justify them in this both by precept and example! . . . Going to California. It is only three thousand miles nearer to hell. . . . Did God direct us so to get our living, digging where we never planted, and He would perchance reward us with lumps of gold? It is a text, oh! for the Jonahs of this generation, and yet the pulpits are as silent as immortal Greece, silent, some of them, because the preacher is gone to California himself. The gold of California is a touchstone which has betrayed the rottenness, the baseness, of mankind. Satan, from one of his elevations, showed mankind the kingdom of California, and they entered into a compact with him at once.

Arrival of the Forty-niners

The discovery of gold in 1848 by James Marshall sparked a massive wave of westward migration. The largest influx occurred in 1849, and those prospectors who sought their fortunes became known collectively as forty-niners, in reference to the year they arrived. Fortune seekers came by land and sea, from every corner of the world. There were three ways to journey to California in the days of the Gold Rush. By far the easiest and most popular route was the “Panama shortcut.” This journey was 7,000 miles and took approximately two to three months. Gold seekers would sail down the eastern coast of the United States to Panama. There they faced a thirty-five mile overland journey through the jungle, cutting across the Isthmus of Panama to reach the waters of the Pacific Ocean. They then boarded another ship which took them north along the western coast of Mexico to San Francisco. As California’s major port city, San Francisco became the gateway to gold.

“Forty-niner” Street Advertiser in Studio, San Francisco, 1890, Unidentified artist, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The second route was also by sea. Although it was the longest in terms of distance, nearly 15,000 miles, it was also the safest route, despite the risk of high waves, frigid temperatures, and a lack of fresh food. Travelers would sail south from the U.S. east coast past South America, down around the tip of Cape Horn, and back north through the Pacific Ocean to California. This route took approximately four to eight months.

The third and most treacherous route was by land – cutting across the continental United States by wagon train. The shortest in terms of distance – only 3,000 miles – the overland journey could take three to seven months. Traveling by ship was costly, so for many this was the only viable option. Travelers feared attacks from American Indians and wildlife, but the biggest threat actually came from diseases and sicknesses such as cholera, diphtheria, “mountain fever” (similar to typhoid), and pneumonia. The hardships that were encountered were numerous; belongings were lost crossing rivers, wagons broke down after encountering barely cleared trails, pack animals dropped dead from exhaustion, and weather ranging from violent thunderstorms and torrential rain to dust storms and scorching heat plagued gold seekers.

In 1849, San Francisco’s population skyrocketed from 812 to 20,000 people. The cost of land soared – the same plot of land which had cost $16 in 1847, sold for $45,000 just eighteen months later. Prices of goods and commodities also rose. Fresh produce was in high demand, with apples selling for $5 each and a dozen eggs for $50.

The reality of the Gold Rush was that people were likely to find greater financial success in selling goods and services to miners than they actually were in mining for gold. Enterprising individuals in the many mining towns that sprang up often made more money than those who mined for gold. Domestic workers could command $200 per month –matching what members of Congress earned. Women, more so than men, profited enormously from the opportunities the Gold Rush provided. The female population was significantly smaller than the male population, and so jobs that were traditionally assigned to women – clothes washing, ironing, and cooking – became in demand and highly paid professions. Artist Charles Christian Nahl’s mother Henriette supported the family by washing miners’ laundry. It has been suggested that the laundry hanging outside the cabin in the background of Miners in the Sierras is a nod to Henriette.

Outcome

There were other gold rushes in North America, most notably the 1896 Klondike Gold Rush in Canada’s Yukon Territory, but none was as historically and culturally significant as the California Gold Rush. The rush produced on average seventy-six tons of gold per year. By the end of the 1850s, it was estimated that $550 million worth of gold had been mined – approximately $187 billion in today’s dollars. The gold rush propelled the expansion and settlement of the western United States on a massive scale. In the years prior to the Gold Rush, a paltry 2,700 settlers had arrived in California. By 1854, more than 300,000 pioneers had settled there, including many settlers from other countries, some from as far as Australia and China.

Mining Technology during the Gold Rush

The painting Miners in the Sierras, depicts a type of mining called placer mining. The figure in the red shirt wields a pick-axe to loosen rock and gravel from the riverbed, while the figure next to him shovels rock into the bed of the long wooden device called a long tom. The long tom is balanced on the rocks of the river in such a way that water can course through it, so that the heavier particles of gold sink and become trapped at the bottom. The second figure in red at the end of the long tom sifts the debris in the box with a shovel. Gold Rush miner Luther M. Schaeffer, a native of Frederick, Maryland, spent nearly three years mining the gold fields in Nevada County, California and recalled the operation of the long tom. The description of the process in his journal entry from 1851 (the same year Miners in the Sierras was painted) makes it clear that this mining technology was already considered to be outdated:

The painting Miners in the Sierras, depicts a type of mining called placer mining. The figure in the red shirt wields a pick-axe to loosen rock and gravel from the riverbed, while the figure next to him shovels rock into the bed of the long wooden device called a long tom. The long tom is balanced on the rocks of the river in such a way that water can course through it, so that the heavier particles of gold sink and become trapped at the bottom. The second figure in red at the end of the long tom sifts the debris in the box with a shovel. Gold Rush miner Luther M. Schaeffer, a native of Frederick, Maryland, spent nearly three years mining the gold fields in Nevada County, California and recalled the operation of the long tom. The description of the process in his journal entry from 1851 (the same year Miners in the Sierras was painted) makes it clear that this mining technology was already considered to be outdated:

Mining implements had undergone a vast improvement since the days of my first experience in mining. Then we used a rocker or cradle; now the ”long-tom” was introduced, by which twenty times as much dirt could be washed out. A long-tom is a trough about sixteen feet long, with a perforated sheet of iron inserted at one end; water is let on, and dirt thrown in, which it is only necessary to stir up and throw out the stones. It was a strange sight to see a hundred men working in pits, some digging, some throwing up the mud and stones, others shoveling it into the box, and others again stirring up the mass and throwing out the rocks. The noise was so great that one could scarcely hear anything beside the incessant rattle, rattle, rattle. Men worked faithfully, constantly and expeditiously.

The heyday of placer mining, or surface mining, occurred between 1848 and 1855. Over 1400 towns or camps were set up along hillsides along mountain streams. Miners worked the streams with long toms searching for gold in the surface gravel, but this supply was depleted rapidly, and placer mining went into a steep decline on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada from 1854 onwards. By the late 1860’s, only part-time miners and miners of Chinese ethnicity (who due to racial prejudice, were excluded from many industrial mines) continued to employ the old-fashioned methods used in placer mining.

During the dry months of the summer and early fall, the lack of rain and scarcity of water made it difficult to run the long toms. In a journal entry from June 14, 1851, about the same time that Nahl was in the mining camp Rough and Ready, miner Luther Schaeffer wrote that:

The great difficulty which miners labored under at this time, was in procuring a sufficient supply of water to wash their ”dirt.” No water and ditch companies had yet been formed, and men who owned valuable claims, were compelled to exercise the patience of grandfather Job, in waiting until the rainy season came around . . . During the summer months not a drop of water descends upon the parched ground, and those settlements destitute of never-failing streams, present a languishing aspect. But the winter months bring copious showers, and during this season everything assumes a cheerful appearance, and the miner’s heart is gladdened.

When surface deposits of gold declined, placer mining and the settlements built for this purpose were abandoned. If the harder to access deposits of gold were to be extracted, a new, more effective method would have to be implemented.

The Transition to Hydraulic Mining

The advent of the Industrial Revolution brought with it a stunning array of technological changes with a wide scope of applicability to different industries. Americans with their eyes on the West saw an opportunity to apply these technologies to the booming mining industry. At the forefront was hydraulic mining, a process in which large, pressurized water cannons propelled hundreds of gallons of water per second to wash away hillsides into sluices where the heavy gold could be separated from lighter particles and debris. This new technology, implemented by large-scale mining corporations, was faster, broader, and less labor intensive than any previous form of mining had been. In his 1873 California guidebook, author Charles Nordhoff described the hydraulic mining process:

Water brought from a hundred and fifty miles away and from a considerable height is fed from reservoirs through eight, ten or twelve in iron pipes through . . . a nozzle, five or six inches in diameter, is thus forced against the side of a hill one or two hundred feet high. The stream when it leaves the pipe has such force that it would cut a man in two if it should hit him. Two or three and sometimes even six such streams play against the bottom of a hill, and earth and stones, often of great size, are washed away until at last an immense slice if hill itself gives way and tumbles down. . . . I suppose they wash away into the sluices half a dozen acres a day, from fifty to two hundred feet deep, and in the muddy torrent which rushes down at railroad speed through the channels prepared for it, you may see large rocks helplessly rolling along. . . the gold is saved in long sluice boxes, through which the earth and water are run, and in the bottom of which gold is caught by quicksilver. . . . But, in order to run off this enormous mass of earth and gravel, a rapid fall must be got into some deep valley or river. . . .the acres washed away must go somewhere and they are filling up the Yuba River. This was once, I am told by old residents, a swift and clear mountain torrent; it is now a turbid and not rapid stream, whose bed has been raised by the washings of the miners not less than fifty feel above its level in 1849. It once contained trout, but now I imagine a catfish would die in it.

As effective as hydraulic mining was, it was not without consequences, as this type of mining was the most damaging to the region’s ecosystem. The lighter debris from the hillsides, including sand, clay, rocks, and wood, was washed downstream, clogging and flooding rivers. Thousands of acres of farmland were buried beneath the silt and debris. The giant nozzles, called monitors, which sprayed the pressurized water onto the hillsides could, depending on the size of the monitor, eject anywhere from 5,000 to 11,000 gallons of water per minute. This caused flooding and mudslides to become major problems. The addition of heavy rains and floods in 1861 and 1862 exacerbated the problem, pushing the silt and debris from mining operations into once-clear streams and rivers of the Sacramento Valley. One observer wrote in January 1862 that “the Central Valley of the state is underwater – the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys – a region 250 to 300 miles long and an average of at least twenty miles wide,” and that prior “to 1848 the [Sacramento] river was noted for the purity of its water, flowing from the mountains as clear as crystal; but, since the discovery of gold, the ‘washings’ render it as muddy as the Ohio in spring flood.”

The farming industry was the hardest hit by the mining activities. The resulting deluge of debris from hydraulic mining had washed silt and sediment – 4.5 million cubic yards annually – onto crop fields and had poisoned water supplies. Yet a cruel paradox existed, for in many cases the farmers owed much of their prosperity to the miners; the wheat, potatoes, and other food commodities grown by farmers were purchased by the ever-expanding mining communities. Any effort to curtail the mining industry would be both a blessing and a curse. The editor of the Nevada City Transcript opined on the dilemma, writing in 1875:

What are the owners of farms to do? It is an industry the whole world desires to foster. The Government will encourage it, notwithstanding agriculture may suffer. Hydraulic mining is in its infancy. The very storms which are so destructive to the valleys are just what the mines require. The sediment, which has been accumulated for years in the ravines and river beds, and preventing a good fall, has all been washed away, and made a place for the deposit of other quantities unwashed . . . It is evident mining will have to be stopped or that country will have to be abandoned for its present purposes, unless some method can be devised to overcome the difficulty. It is certain mining will never be stopped . . . What relief can be afforded we cannot apprehend.

Additional economic activities needed to support mining operations, such as hunting and fishing, also took their toll on the environment. The fish and wild game populations were absolutely devastated with the influx of miners in the years after the start of the Gold Rush. Already by 1877, residents were complaining to the state government of the conditions, stating that “a few years ago deer and kindred game were plentiful; in our mountains and valleys [because of] the wanton destructions of these animals [they] . . . will soon become extinct.”

Conservation Movement in California

Today with our twenty-first century eyes, it is easy to view the destruction caused by hydraulic mining and think about the long-term effects. Yet, in the nineteenth century, Americans were far less, if at all, concerned with the long-term effects of the hydraulic technique as they were with its output and the large financial gains to be made. This is because a unique dichotomy existed in the mind of the nineteenth century American, where a harmonious intersection between industry and the natural world existed, and was in fact celebrated. Nature was prized for very different reasons than we celebrate it today. Then, nature was valued for its ability to promote a particular sensibility. The first preserved lands in the nation, such as Yosemite in 1868, were not set aside for modern-day conservation concerns, but rather they were preserved for their potential to produce natural resources. It was believed that by tapping into natural resources, Americans could transform the beautiful, yet unproductive and uncivilized, wilderness into an equally beautiful, yet cultivated and bountiful garden. This sentiment was very much in keeping with the idea of manifest destiny, that it was the duty of Americans to civilize and settle the land from Atlantic to Pacific. Therefore it should come as no surprise that Carleton Watkin’s photographs were at the time, celebrated for both their representations of both nature and industry.

As long as the extraction of resources did not interfere with those elements of the landscape which provided Americans with a visual representation of their cultural values (e.g. vistas and geological formations), the public had no objection to such activities as mining, land development, farming etc. It was thought that the natural world was actually improved when man interfered and put his mark on nature. Whereas today, we value the American wilderness as an example of the world untouched by mankind; one that must be preserved from any kind of human interference or development.

There were some observers, however, who lamented the transformation of the California landscape by mining operations. In 1857 traveler J.D. Borthwick stated, “Young as California was, it was in one respect older than its parent country, for life was so fast that already it could show ruins and deserted villages . . . even villages of thirty or forty shanties were to be seen deserted and desolate, where the diggings had not proved so productive.” Lorenzo Sawyer, later chief justice of the California State Supreme Court, wrote as early as 1850 that miners had spoiled the California landscape: “Cast your eye along those vallies [sic], Deer creek, Little Deer creek, Gold run and many others, see their beds to a great depth thrown up, behold the pine, the fir, the cedar, the oak, these monarchs of the forest undermined, uprooted.”

After observing the crippling effects mining activities had on the environment, wilderness conservationist John Muir remarked that “the hills have been cut and scalped and every gorge and gulch and broad valley have been fairly torn to pieces and disemboweled, expressing a fierce and desperate energy hard to understand.” Likewise, in his 1868 survey of California’s natural resources, author Titus Fey Cronise lamented the havoc the mines had caused:

By no other means does man so completely change the face of nature than by this process of hydraulic mining. Hills melt away and disappear under its influence. . . . The desolation that remains after the ground, thus washed, is abandoned, is remediless and appalling. The rounded surface of the bed rock, torn with picks and strewn with enormous boulders too large to be removed, shows here and there islands of the poorer gravel rising in vertical cliffs with red and blue stains, serving to mark the former levels, and filling the minds with astonishment at the changes, geologic in their nature and extent, which the hand of man has wrought.

The expanding ecological disasters caused by hydraulic mining did little to slow down operations, despite the constant complaints of farmers and valley landholders. Industrialists were not unaware of the resulting conditions, and certainly the profits produced for them by the exploitation of gold and other resources outweighed any concerns during the 1850s and 1860s. The mining companies also had far too much political influence for any complaints from farmers or land holders to take effect. It took many sessions of the California state legislature and the U.S. Congress before any regulations were put into place. Even then, the regulations were largely ineffectual until 1884 when a federal injunction finally put an end to hydraulic mining. It has been estimated that nearly one third of the gold extracted during the Gold Rush era, approximately $100 million worth, was extracted by hydraulic mining.

Primary Source Connections

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo – February 2, 1848

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo – February 2, 1848

View at the National Archives

“This treaty, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the war between the United States and Mexico. By its terms, Mexico ceded 55 percent of its territory, including parts of present-day Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah, to the United States.”

John Sutter’s 1857 narrative, “The Discovery of Gold in California”

John Sutter’s 1857 narrative, “The Discovery of Gold in California”

Read and Download at Archive.org (Excerpt from page 193)

It was in the first part of January, 1848, when the gold was discovered at Coloma, where I was then building a saw-mill. The contractor and builder of this mill was James W. Marshall of New Jersey. . . . It was a rainy afternoon when Mr. Marshall arrived at my office in the Fort, very wet. I was somewhat surprised to see him, as he was down a few days previous; and when, I sent up to Coloma a number of teams with provisions, mill irons, etc., etc. He told me then that he had some important and interesting news which he wished to communicate secretly to me, and wished me to go with him to a place where we should not be disturbed, and where no listeners could come and hear what we had to say. I went with him to my private rooms . . . I forgot to lock the doors, and it happened that the door was opened by the clerk just at the moment when Marshall took a rag from his pocket, showing me the yellow metal; he had about two ounces of it . . . he told me that he had expressed his opinion to the laborers at the mill, that this might be gold; but some of them were laughing at him and called him a a crazy man, and could not believe such a thing. After having proved the metal with aqua fortis, which I found in my apothecary shop, likewise with other experiments, and read the long article “gold” in the Encyclopedia Americana, I declared this to be gold of the finest quality, of at least 23 carats. . . . So soon as the secret was out my laborers began to leave me, in small parties first, but then all left, from the clerk to the cook. . . . Then the people commenced rushing up from San Francisco and other parts of California, in May, 1848: in the former village only five men were left to take care of the women and children. The single men locked their doors and left for “Sutter’s Fort,” and from there to the Eldorado.

The Shirley Letters from California Mines in 1851-52

The Shirley Letters from California Mines in 1851-52

Read and Download at Archive.org or Read a transcript at the Library of Congress

Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe (1819-1906), later writing under the pseudonym “Dame Shirley,” accompanied her physician-husband to California in 1849. The couple first lived in mining camps where Dr. Clappe practiced medicine and then moved to San Francisco, where Dame Shirley taught in the public schools for more than twenty years. In this book, which is comprised of letters to her sister, Dame Shirley writes of life in San Francisco and the Feather River mining communities of Rich Bar and Indian Bar.

Literary Connections

Fiction:

The Call of the Wild, 1903, Jack London

Read it and Download at Archive.org

The search for gold in America began in earnest after 1849 when gold was found at Sutter’s Mill, California. A second gold rush occurred in 1896 when gold was found in the Klondike region of Canada. More than 100,000 migrated in search of their fortune. While this book is set during the 1896 gold rush, the novel’s themes of migration and civilization versus nature can also be found in the two highlighted artworks from the first Gold Rush of 1849.

“All Gold Cañon,” 1905, Jack London (short story)

“All Gold Cañon,” 1905, Jack London (short story)

Read it online.

Jack London wrote many short stories exploring the Gold Rush, but non so succinctly captures the gold lust that gripped the mid-nineteenth century and the hazards of that greed quite like “All Gold Cañon.” This short story originally appeared in The Century Magazine (at left) in 1905, and is set in a remote canyon in California’s Sierra Nevada region.

The Ballad of Lucy Whipple, 1996, Karen Cushman – Grades 5 to 7

The Ballad of Lucy Whipple, 1996, Karen Cushman – Grades 5 to 7

Find it in a Library

“When California Morning Whipple’s widowed mother uproots her family from their comfortable Massachusetts environs and moves them to a rough mining camp called Lucky Diggins in the Sierras, California Morning resents the upheaval. Desperately wanting to control something in her own life, she decides to be called Lucy, and as Lucy she grows and changes in her strange and challenging new environment.” – KarenCushman.com

“How I Went to the Mines,” 1903, Bret Harte (short story)

“How I Went to the Mines,” 1903, Bret Harte (short story)

Read it at Archive.org (page 335)

American author Bret Harte moved to California in 1853, where he worked as a school teacher and tried his hand at prospecting for gold. Many of his most memorable short stories are set during the California Gold Rush. Like his friend Mark Twain, Harte incorporated elements from his own life experiences to inform his stories, leaving the reader to wonder whether this short story contains more fact than fiction.

Non-Fiction:

Roughing It, 1872, Mark Twain

Roughing It, 1872, Mark Twain

Read it and Download at Archive.org (Excerpt from page 414)

Mark Twain traveled throughout the American West with his brother, Orion Clemens, from 1861 to 1867. They traveled from town to town, working a variety of jobs including prospecting silver and gold and speculating in real estate. Roughing It is Twain’s semi-autobiographical novel of these travels. The book combines a first-hand account of life in the untamed Wild West and Twain’s signature style of humor. In the following excerpt, Twain describes those who lived in the mining camps:

It was an assemblage of two hundred thousand young men — not simpering, dainty, kid-gloved weaklings, but stalwart, muscular, dauntless young braves, brimful of push and energy . . . the very pick and choice of the world’s glorious ones. No women, no children, no gray and stooping veterans, — none but erect, bright-eyed, quick-moving, strong-handed young giants — the strangest population, the finest population, the most gallant host that ever trooped down the startled solitudes of an unpeopled land. . . . It was a splendid population — for all the slow, sleepy, sluggish-brained sloths staid at home — you never find that sort of people among pioneers — you cannot build pioneers out of that sort of material. It was that population that gave to California a name for getting up astounding enterprises and rushing them through with a magnificent dash and daring and a recklessness of cost or consequences, which she bears unto this day. . . . They cooked their own bacon and beans, sewed on their own buttons, washed their own shirts – blue woolen ones; and if a man wanted a fight on his hands without any annoying delay, all he had to do was to appear in public in a white shirt or a stove-pipe hat, and he would be accommodated. For those people hated aristocrats. They had a particular and malignant animosity toward what they called a “biled shirt.” It was a wild, free, disorderly, grotesque society! Men — only swarming hosts of stalwart men — nothing juvenile, nothing feminine, visible anywhere!

Artwork Connections

Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania, ca. 1861, James Hamilton

Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania, ca. 1861, James Hamilton

Rouseville, Pennsylvania, lay within a few miles ofTitusville and Pithole City, two of the most famous boomtowns in Pennsylvania ’s oil fields. From 1859 until after the Civil War, new gushers brought investors, cardsharps, saloons, and speculators into these rural settlements. As quickly as they grew, however, the towns collapsed, often from the effects of fires like the one shown here. In the 1860s, American industrialist John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) was in the thick of this oil boom, maneuvering to establish the Standard Oil Company. Rockefeller’s investments in railroads and refineries would make him one of America’s richest men, long after the wildcatters in the Pennsylvania fields had gone bust.

“Forty-niner” Street Advertiser in Studio, San Francisco, 1890, Photographer unknown

“Forty-niner” Street Advertiser in Studio, San Francisco, 1890, Photographer unknown

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: History

On the Water: To California By Sea – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

This section, part of a larger online exhibition, presents artifacts from the Smithsonian’s collection, classroom resources, and a teacher’s guide based on the California Gold Rush.

Glossary

1845 annexation of Texas: the incorporation of the Republic of Texas into the United States of America. In 1836 the Texian Army won the Battle of San Jacinto against Mexican forces, led by famed general Santa Anna, and the Republic of Texas declared its independence from Mexico. But Mexico had refused to acknowledge this action and warned the U.S. that if it tried to make Texas part of the U.S., Mexico would declare war. In 1845 Texas voluntarily asked to join the U.S., and became the 28th state. This action led to Mexico to declare war on the United States, starting the Mexican-American War.

forty-niners: people, especially prospectors, who went to California in 1849 during the gold rush.

Henry David Thoreau: (1817-1862) American author and poet, best known for his work Walden (1854), a novel that is both memoir, social experiment, and a voyage of spiritual discovery. It is a reflection of a man’s experience living simply in nature, outside “civilized” society.

Industrial Revolution: a series of economic, social, and technological changes in America, characterized by the replacement of hand tools with power-driven machines, the growth of factories, and the mass production of goods.

John Muir: (1838-1914) American environmental philosopher, author, and early proponent of wilderness preservation. Founder of the Sierra Club, a prominent conservation organization.

John Sutter: (1803-1880) German-born Swiss settler and colonizer of California. The discovery of gold on his land at Sutter’s Mill precipitated the California Gold Rush.

Klondike Gold Rush: (1896-1899) a migration by approximately 100,000 prospectors to the Klondike region of the Yukon in north-western Canada. Similar to the California Gold Rush, while the very first prospectors did find gold, most found their search in vain.

long tom: a trough for washing gold-bearing deposits.

Manifest Destiny: the nineteenth-century doctrine or belief that the expansion of the U.S. throughout the American continents was both justified and inevitable.

Mexican Cession: the historical name for the region of the United States that Mexico ceded to the U.S. in the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848.

placer mining: the mining of placers, or mineral deposits, in a stream or river bed for precious metals such as gold.

Ralph Waldo Emerson: (1803-1882) American poet, essayist, and philosopher; founder of the Transcendentalist philosophical movement.

Santa Anna: (Antonio López de Santa Anna) (1794-1876) influential Mexican military and political leader, best known for his victory at the Battle of the Alamo in 1836.

sluices: long inclined troughs with strips of wood or metal laid perpendicular to the trough so as to catch the gold during mining operations while allowing the water and debris to slide down the trough.

Sutter’s Mill: the water-powered saw mill owned by John Sutter, where gold was discovered in 1848, setting off the California Gold Rush. It was located in present-day Coloma, California on the bank of the South Fork American River.

Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo: (February 2, 1848) the agreement between the United States and Mexico which ended the Mexican-American War.

washings: excess mining material, including gold dust, gravel, and other minerals; essentially the debris and refuse from mining operations.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 4 – Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

- Standard 1C – The student understands the ideology of Manifest Destiny, the nation’s expansion to the Northwest, and the Mexican-American War.

- 5-12 – Explain the causes of the Texas War for Independence and the Mexican-American War and evaluate the provisions and consequences of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

- Standard 2A – The student understands how the factory system and the transportation and market revolutions shaped regional patterns of economic development.

- 5-12 – Explain how the major technological developments that revolutionized land and water transportation arose and analyze how they transformed the economy, created international markets, and affected the environment.

- Standard 2C – The student understands how antebellum immigration changed American society.

- 5-12 – Analyze the push-pull factors which led to increased immigration, for the first time from China but especially from Ireland and Germany.

- Standard 2E – The student understands the settlement of the West.

- 5-12 – Explore the lure of the West and the reality of life on the frontier.

U.S. History Content Standards Era 6 – The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

- Standard 1C – The student understands how agriculture, mining, and ranching were transformed.

- 5-12 – Explain how major geographical and technological influences, including hydraulic engineering and barbed wire, affected farming, mining, and ranching.

- Standard 1D – The student understands the effects of rapid industrialization on the environment and the emergence of the first conservation movement.

- 7-12 – Explain how rapid industrialization, extractive mining techniques, and the “gridiron” pattern of urban growth affected the scenic beauty and health of city and countryside.