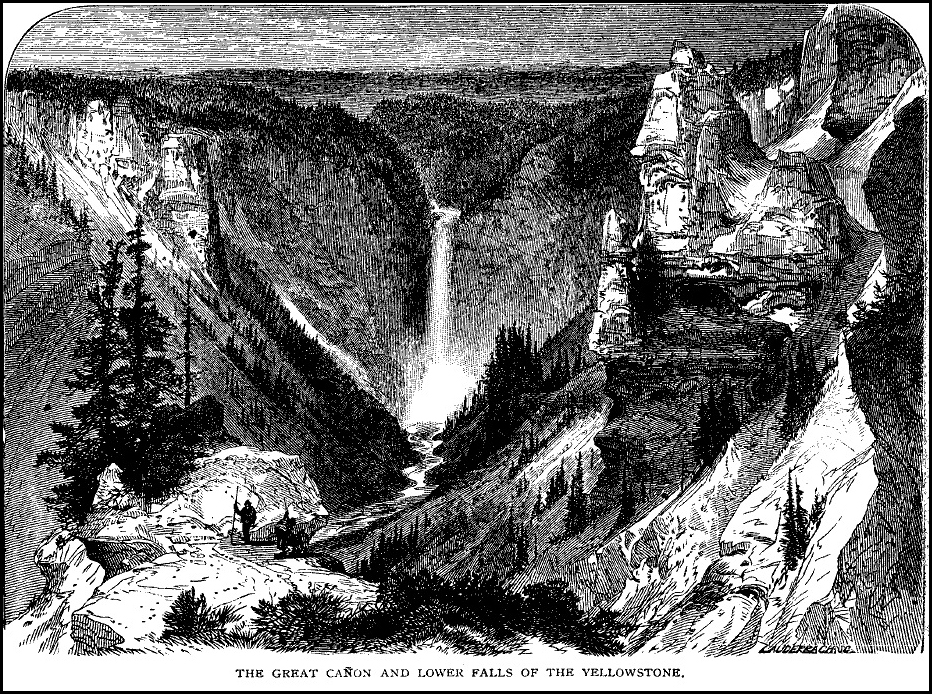

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1872, Thomas Moran

With technology and manufacturing evolving at a rapid pace, some Americans began to wonder if these new advancements were having negative effects on the environment. This concern birthed the conservation movement and the effort to preserve our nation’s natural wonders for generations to come. Artist Thomas Moran accompanied the first federally funded geological survey to Yellowstone to help document and explore features of the region. Just one year later, Yellowstone National Park would become the first national park in the United States. The grandeur of Moran’s canvas of the Yellowstone showed an amazed and awed public back east the natural beauty that needed to be preserved. In a painting of another natural wonder, the majesty of Niagara Falls is obscured by the dark smoke billowing from a paper mill smokestack. The expanding industrial center around Niagara Falls prompted law makers to sign a bill that by the 1880s turned the area into a park and state reservation. George Inness’s ambiguous canvas of the falls leaves us to wonder whether the mist pervading the canvas is from the falls or the factory.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What can we learn about Americans’ view of the West in the 1870s from this painting? How did Thomas Moran’s portrayals of Yellowstone contribute to its establishment as the first national park? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

What role do light and shadow play in the composition of this landscape?

Strong diagonal lines guide the viewer’s eye back and forth between starkly contrasting areas of light and dark. The lower two corners of the composition are shrouded in shadow, leading our eye up and down the rocky slopes of the canyon, bathed in warm, golden sunlight in the center of the canvas. Our eye descends toward the brilliant blue river at the bottom of the chasm and to the white spray rising from the powerful waterfall – the lightest part of the painting. The contrast between light and shadow as well as Moran’s use of color creates a stunning visual effect that highlights the grandeur of the natural landscape.

Strong diagonal lines guide the viewer’s eye back and forth between starkly contrasting areas of light and dark. The lower two corners of the composition are shrouded in shadow, leading our eye up and down the rocky slopes of the canyon, bathed in warm, golden sunlight in the center of the canvas. Our eye descends toward the brilliant blue river at the bottom of the chasm and to the white spray rising from the powerful waterfall – the lightest part of the painting. The contrast between light and shadow as well as Moran’s use of color creates a stunning visual effect that highlights the grandeur of the natural landscape.

There are a few small figures included in the painting. Using the detail images, what do you think is going on?

We see three horses and four men, including one who appears to be a Native American in full regalia. One of the men stands on the edge of the bluff with the Native American, stretching his arm out pointing at the grand vista before him. The other two men stay with the horses, and one is sitting down holding an open book – possibly a sketchbook or journal. We can infer that this is an expeditionary party exploring and surveying Yellowstone, probably with the Native American as their guide. The humans’ tiny scale in relation to the landscape heightens the power and majesty of the canyon.

We see three horses and four men, including one who appears to be a Native American in full regalia. One of the men stands on the edge of the bluff with the Native American, stretching his arm out pointing at the grand vista before him. The other two men stay with the horses, and one is sitting down holding an open book – possibly a sketchbook or journal. We can infer that this is an expeditionary party exploring and surveying Yellowstone, probably with the Native American as their guide. The humans’ tiny scale in relation to the landscape heightens the power and majesty of the canyon.

What geological elements do you notice?

Steam from geysers, Yellowstone’s most distinctive geological feature, rises in the top left of the painting, off in the distance beyond the falls. Evidence of erosion, a natural geological process caused over time by weather forces such as wind, water, ice, and waves, is visible in the stone cliffs. The distinctive yellow color of the stone in the Canyon is a result of exposure to the elements, and indicates the presence of iron in the rock, which is oxidizing it and causing the Canyon to effectively rust.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

A party of men, having arrived on horseback, look out from a shadowy bluff onto the stunning vista of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, glimmering golden in the sunlight. While the exact scene in Moran’s painting may be fictionalized, it parallels a real-life expedition that Moran took part in, which had momentous influence on the founding of Yellowstone as the first national park.

In 1871, Moran made the trip to Yellowstone accompanying the scientists of Ferdinand Hayden’s United States Geological Expedition, tasked with documenting the region through sketches and paintings. A photographer, William Henry Jackson, was also among the party. Before Moran and Jackson’s images were brought back to the East, most Americans had never seen a visual representation of Yellowstone. Moran’s sketches and watercolors, along with Jackson’s photographs and the geological samples brought before Congress, played a major role in the passing of the legislation that declared Yellowstone the first national park in 1872.

Moran’s painting does not depict a single accurate vantage point of the Canyon, but rather an imagined view that combines several vantage points in order to “bring before the public the character of that region” (Moran, quoted in George Sheldon’s 1881 book American Painters). While Moran was most concerned with conveying the overwhelming sense of grandeur and scale of the canyon and falls, he also took care to accurately depict the unique features of the region like the geysers and color of the rocks in the Canyon. Gaining recognition for the existence of these geological wonders was critical to ensuring that Yellowstone would be protected in perpetuity.

Niagara

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What can we learn from this painting about industrialization and its impact on Niagara Falls during the 19th century? What clues does George Inness give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

How would you describe the style in which George Inness painted Niagara Falls?

Instead of concerning himself with precise details, Inness seems to have been more interested in conveying an impression of what it felt like to visit Niagara Falls. The brushstrokes are soft and painterly, avoiding defined lines or geometric shapes. Colors have been blended and blurred, yet we still get a sense of where the land ends and the water begins. Inness’s stylistic choices seem to be about conveying the feeling of elements like air, water, mist, and smoke, rather than a hyper-realistic depiction of Niagara Falls.

Instead of concerning himself with precise details, Inness seems to have been more interested in conveying an impression of what it felt like to visit Niagara Falls. The brushstrokes are soft and painterly, avoiding defined lines or geometric shapes. Colors have been blended and blurred, yet we still get a sense of where the land ends and the water begins. Inness’s stylistic choices seem to be about conveying the feeling of elements like air, water, mist, and smoke, rather than a hyper-realistic depiction of Niagara Falls.

What can we tell about the environment surrounding Niagara Falls from Inness’s painting?

The most prominent feature on the painting’s horizon line is a smokestack, perhaps from a factory or industrial plant, emitting a cloud of dusty purple smoke into the sky. The industrial smoke both parallels and contrasts with the visual effect of the mist rising from the bottom of the falls.

The most prominent feature on the painting’s horizon line is a smokestack, perhaps from a factory or industrial plant, emitting a cloud of dusty purple smoke into the sky. The industrial smoke both parallels and contrasts with the visual effect of the mist rising from the bottom of the falls.

We also see some small figures in the bottom left section of the painting, which helpfully give us a sense of scale, emphasizing how enormous the falls are in comparison to humans. Our eyes our drawn to these figures by the bright specks of white paint Inness has used, that suggest paper or canvas. Are these figures artists like Inness, capturing the falls? Or are they tourists, holding maps?

Interpretation: What does it mean?

George Inness painted Niagara Falls in a way that addresses the environmental impact humans have had upon this great natural wonder. Using an impressionistic painting style, Inness has created a haze over the scene, a blend of natural mist and industrial smoke. By including the smokestack so prominently in his composition, Inness confronts the viewer with evidence of the over-development and tourism-driven industrialization that surrounded Niagara Falls in the late 19th century.

Historical Background

Art and the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871

1871 Hayden Survey at Mirror Lake, en route to East Fork of the Yellowstone River, August 24, 1871, William Henry Jackson, United States Geological Survey Photographic Library

Beginning with Lewis and Clark’s travels through the Louisiana Purchase in 1804-1806, exploratory expeditions became one of the primary means by which the Federal Government gathered information about its vast resources. Prior to the Civil War these expeditions were primarily military in nature, focusing on issues such as international land disputes and routes for wagon trains and railroads. After the war, new interest developed in further investigating the characteristics of the land to promote settlement, tourism, commerce, and to exploit natural resources.

By 1871, the time was ripe for an organized scientific survey of the Yellowstone area, one that would collect paleontological, botanical, zoological, and geological specimens, and record temperature and weather patterns. One of the preeminent explorers of the day, American geologist Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden, petitioned Congress to fund a survey to the Yellowstone. As an experienced surveyor, Hayden’s research trip began in earnest after the Civil War, when he was appointed geologist-in-charge of the U.S. Geological Survey. The goals outlined for Hayden’s proposed survey were ambitious: to explore “all the beds, veins and other deposits of ores, coals and clays, marls, peats and other such mineral substances as well as the fossil remains of the various formations,” and to compile “ample collections in geology, mineralogy, and paleontology to illustrate notes taken in the field.” His team would take soil samples for agricultural planning, estimate mineral yields, and comment on the land’s commercial potential. “Graphic illustrations” of landscapes were to be made in order to convey something of the appearance of the region. Hayden’s findings were to be submitted in reports to those in Washington, D.C. with a vested interest in such research – the Department of the Interior, the Department of War, and the Smithsonian Institution. These reports would aid in determining land use and would add to the general knowledge of our nation’s expanded terrain.

Because of the U.S. government’s interest in determining the land’s usage, it agreed to Hayden’s proposal and underwrote his survey – the first federally funded government survey in American history. Of the importance of the surveys, Hayden wrote, “We have beheld, within the past fifteen years, a rapidity of growth and development in the Northwest which is without a parallel in the history of the globe. Never has my faith in the grand future that awaits the entire West been so strong as it is at the present time, and it is my earnest desire to devote the remainder of the working days of my life to the development of its scientific and material interests, until I see every Territory, which is now organized, a State in the Union.”

The survey began on June 1, 1871, departing from base camp in Ogden, Utah. Accompanying Hayden were over thirty team members, including military escorts, botanists, meteorologists, ornithologists, hunters, guides, topographers, cooks, and physicians. By July the team had reached Montana, where artist Thomas Moran joined the expedition. Hayden outlined the survey’s route in a letter to the Secretary of the Interior before departing base camp:

Our route will be along the mail route to Virginia City, and Fort Ellis. We have already made the necessary observations in this valley and propose to connect our work Topographical and Geological with the Pacific Rail Road line. We then propose to examine a belt of country, northward fifty to one hundred miles in width to Fort Ellis, which point we hope to reach about the 10th or 15th of July. The remainder of the season we desire to spend about the sources of those rivers—Yellowstone, Missouri, Green, and Columbia, which have their sources near together in this region.

Hayden’s official report on the Yellowstone region explained the importance of further scientific explorations: “We saw many strange and wonderful phenomena, many things which would require volumes for adequate description, and which in future geography will be classed among the wonders of the earth; yet we only followed up the Yellowstone River, passed around two sides of the lake, and down one branch of the Madison to the main stream. We did not explore one-third of the Great Basin. The district will be in easy reach of travel if the Union Pacific Railroad comes by way of the lower Yellowstone Valley. . . . As a country for sight-seers, it is without parallel; as a field for scientific research, it promises great results; in the branches of geology, mineralogy, botany, zoology, and ornithology it is probably the greatest laboratory that nature furnishes on the surface of the globe.”

It may surprise us today that the most famous and earliest American expedition westward, that of Lewis and Clark, excluded the services of an artist – an astounding omission by President Thomas Jefferson who had overseen preparations for the expedition. Jefferson had instructed the explorers to record anything and everything they encountered. But he could not have foreseen that the surveyors would come across sights that might have been indescribable in writing. As such, Meriwether Lewis took it upon himself to make crude drawings in his notebook, but he noted that he wished for a better means with which to record his experience, specifically referring to the visual medium when facing the Great Falls of the upper Missouri River: “After wrighting [sic] this imperfect description I again viewed the falls and was so much disgusted with the imperfect idea which it conveyed of the scene that I determined to draw my pen across it and begin again . . . I wished . . . that I might be enabled to give to the enlightened world some just idea of this truly magnificent and sublimely grand object.”

After Lewis and Clark’s landmark journey, very few major expeditions went without some form of visual documentation. After the Civil War, almost every government funded expedition included both an artist and a photographer. Photography produced an image of undeniable fidelity to its subject, but traditional artists remained a vital part of the expeditionary teams. Sketches, drawings, and paintings were able to convey one crucial detail that photography at the time could not – color. The watercolors and oil paintings produced out of these surveys were exceptionally useful for survey leaders in lobbying Congress and proving the claims about the West’s dramatic chromatic variations. Expeditionary illustrations amplified the findings of geologists, topographers, and geographers. They were also exhibited independently as landscape art, augmented popular magazines and travel guidebooks, and were sold to the public in chromolithographic reproduction. The artistic renderings of the expeditions were also advantageous to commercial enterprises such as publishing houses and real estate developers, which capitalized on the expedition results for their own benefit. Financiers were eager to extend the Northern Pacific Railroad, the northern-most transcontinental railroad, to the Pacific. Artistic images enhanced their efforts to gain support. Additionally, the railway companies had an interest in locating their rail routes close to potential coal sources for locomotive fuel. Hayden’s survey results would inform them of these sources. The relationship with railway companies were not one-sided, however, as the companies provided Hayden and his team with cheap rates for transporting supplies, horses, and equipment.

It is difficult to imagine now, with our wealth of media, just how important and unique the landscape sketches, paintings, and photographs by these artists and photographers were to an eager eastern public and to the policymakers who administered the unsettled lands. The terrain in these works – vast treeless plains and massive snow-capped mountains – were substantially different from that of the settled East. The availability of pictures of these locations made the West seem more real and accessible to an eastern audience. Hayden believed in the power of the image over the descriptive verse of the written word. He relied heavily on photographs and Thomas Moran’s sketches and oil paintings to convince Congress of the importance of continued geological surveys. Hayden felt that these images were “the nearest approach to a truthful delineation of nature” and that “to the intelligent eye they speak for themselves better than pages of description.”

Thomas Moran

Thomas Moran (center) and William Henry Jackson (right) in Piute country, New York Historical Society

Thomas Moran first became interested in the spectacular landscape features of Yellowstone in the spring of 1871 when his friend Richard Watson Gilder, editor of Scribner’s Monthly, asked him to finish some sketches that had been made by amateur draftsmen during an earlier expedition to Yellowstone. The result was one of the first published descriptions of the dramatic geographical features of this area of Wyoming featuring geysers and hot springs, among other volcanic phenomena. Yellowstone had long been known by Indians and mountain men, but their stories of the hellish place of smoke and steam had been dismissed as invention.

Beginning in 1870, all of Hayden’s expedition parties included a draftsman of some kind to provide visual documentation. Hayden brought on photographer William Henry Jackson to the survey party, as well as prominent landscape painter Sanford Robinson Gifford. Gifford helped Jackson with his photographic work and also made his own drawings and oil sketches of the landscapes explored by the expedition that year. But by 1871, Gifford did not continue with Hayden’s expeditions. A. B. Nettleton, office manager of the Northern Pacific Railroad and a friend of Moran’s, wrote to Hayden introducing Moran and asking Hayden to add Moran to the 1871 expedition:

My friend, Thos. Moran, an artist of Philadelphia of rare genius, has completed arrangements for spending a month or two in the Yellowstone country, taking sketches for painting. He is very desirous of joining your party at Virginia City or Helena, and accompanying you to the head of the Yellowstone. I have encouraged him to believe that you [would] be glad to have him join your party, & that you would in all probability extend to him every possible facility. Please understand that we do not wish to burden you with more people than you can attend to, but I think that Mr. Moran will be a very desirable addition to your expedition, and that he will be almost no trouble at all . . . He, or course, expects to pay his own expenses, and simply wishes to take advantage of your cavalry escort for protection.

Moran caught a Union Pacific train from his home in Philadelphia to Utah, then rode a stage coach to catch up with the expedition in Montana. The artist immediately took to working in a place unlike any he had ever seen. Decades later, William Henry Jackson published an article about their experiences together in the Yellowstone. Of Moran, Jackson wrote:

He was 34 years old, at this time, of slight and frail physique and did not seem to be of the kind to endure the strenuous life of the wilderness. But he was wiry and active in getting about and keenly enthusiastic about his participation in the work of the expedition. He had never camped out before . . . This was his first experience in Rocky Mountain regions, coming out entirely unacquainted with his associates, or with the country itself and all that related to it. But he made the adventure with fine courage and quickly adapted himself to the new and unfamiliar conditions and, as it turned out later, none was more untiring on the trail, or less mindful of unaccustomed food or hard bed under a little shelter tent, than he was.

The Industrialization of Niagara Falls

George Inness at Niagara Falls, ca. 1884, Archives of American Art

Of all the natural wonders of the United States, it was Niagara Falls which fascinated Americans most. Celebrated in gift books and guides on American scenery, the power of the falls had no equal in the U.S. or Europe. Tourists flocked to the sublime natural wonder. Niagara Falls became an icon of national pride, with the geology of the falls becoming somewhat of a national passion. During the first half of the nineteenth century, the science of geology was one of the few arenas in which the United States surpassed its European peers. Guidebooks provided visitors with precise information about the mineralogical formations visible from the staircase which led visitors to the base of the falls. American citizens spoke with great pride and authority on Niagara’s rocky erosions and sedimentary shifting. Many Americans, especially followers of Transcendentalism, saw this natural wonder as evidence of a divine power on earth.

Artist George Inness became completely smitten with the natural wonder of the falls when he first visited in 1881. Determined to take the “impression of the falls down right away,” but having arrived without painting materials, Inness rushed to the nearby Buffalo, New York studio of an old friend to acquire supplies. At the same time Inness was creating a series of paintings based on Niagara Falls, the location was undergoing a radical energy transformation brought on by the continued developments of the Industrial Revolution. The Niagara Falls Power Company and numerous partners were working to harness the power of the falls to bring the first hydro-electric power plant to Niagara. Yet, as physical changes brought on by industrial development and shifts in ideas about nature and preservation began to change, so too did the manner in which the falls were viewed and depicted by artists.

Industrialization

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, landowners and entrepreneurs had been busy developing flashy amusements, hotels, and facilities for tourists, as well as constructing large mills and factories – all of which encroached upon the riverbanks of the Falls. In Inness’ Niagara, the billowing smokestack in the background of the painting belongs to a paper mill constructed in the middle of the Niagara River on Bath Island (now Green Island). One traveler to Bath Island in 1831 reported that Bath Island contained “a large paper mill, as well as other mills. There is also a house where the weary traveler may find most comfortable refreshment and dinner.” The impending construction of a large distillery on the adjacent Goat Island became a major point of contention between industrialists and preservationists. In 1872, Picturesque America opined that the increased industrialization of the area made Niagara resemble “a superb diamond set in lead. . . . The stone is perfect, but the setting is lamentably vile and destitute of beauty.”

Many agreed that one of the greatest affronts to Niagara’s natural beauty was electric lighting, first powered in 1879. In a series of letters to newspapers, collectively published in 1882 as The Conditions of Niagara Falls and the Measures Needed to Preserve Them, author J.B. Harrison likened the illumination to “a poor circus with a cheap celebration on the Fourth of July. No description can give to those who have not seen it an adequate notion of the abominable effect of the colored electric lights when directed upon the Falls. It is debasing, vulgarizing, and horrible in the extreme. . . . It is evident that neither the people who make this exhibition nor those who enjoy it would have any rooted objection against the actual defilement of these crystal waters, as their taste is actually so perverted that they have no joy in their purity or beauty.”

Entrepreneurs proposed numerous schemes to harness the “foam and fury” of the falls. By the 1880s, the Niagara Falls Power Company and their numerous partners worked out the technological systems necessary to harness the power of the falls for the generation and transmission of electricity on a magnitude that had never been attempted. The project required not only the complete rethinking of earlier generations of turbines and motors but also the invention of a host of new generators, transformers, and transmitters that didn’t yet exist. One of the visionaries of the project was Nikola Tesla, who said that Niagara contained enough power to “light every lamp, drive every railroad, propel every ship, heat every store, and produce every article manufactured by machinery in the United States.” The mammoth hydro-electric power plant at Niagara Falls opened in 1895. In his speech at the opening ceremony, Tesla underscored the significance of this achievement:

We have many a monument of past ages; we have the palaces and pyramids, the temples of the Greek and the cathedrals of Christendom. In them is exemplified the power of men, the greatness of nations, the love of art and religious devotion. But the monument at Niagara has something of its own, more in accord with our present thoughts and tendencies. It is a monument worthy of our scientific age, a true monument of enlightenment and of peace. It signifies the subjugation of natural forces to the service of man, the discountinuance of barbarous methods, the relieving of millions from want and suffering.

Preservation and Conservation

The last quarter of the nineteenth century saw an increased effort to reclaim the natural beauty of Niagara Falls due to the area’s heightened industrialization. American preservationists insisted that the cataract was a national treasure that belonged to the whole country and was worthy of safeguarding for future generations. The campaign to preserve the falls’ beauty and banish the factories and tourist traps that had marred the surrounding landscape was led by artist Frederic E. Church and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Church proposed that the State of New York establish a public park at the falls with free public access, protecting the area from incursions of sideshows, souvenir shops, and factories. Olmsted argued that the natural wonder of Niagara Falls had been turned into a series of commodities for the consumption of the tourist, writing in 1879:

The aim to make money by the showman’s methods; the idea that Niagara is a spectacular and sensational exhibition, of which roper-walking, diving, brass bands, fireworks and various “side-shows” are appropriate accompaniments, is so presented to the visitor that he is forced to yield to it, and see and feel little else than that prescribed to him. . . . Visitors are so much more constrained to be guided and instructed, to be led and stopped, to be “put through,” and so little left to natural and healthy individual intuitions.

The design for the public park designed by Olmsted and fellow landscape architect Calvert Vaux was picturesque: winding walking paths close to the water, places for sitting and standing, and carriage roads that were set back from the water’s edge. All man-made structures, such as restrooms, were to be as unobtrusive as possible and hidden behind screens of trees. Olmsted’s preservationist philosophy was outlined in his 1868 report on the Yosemite, a philosophy that extended to his work on Niagara: “The first point to be kept in mind then is the preservation and maintenance as exactly as is possible of the natural scenery; the restriction, that is to say, within the narrowest limits consistent with the necessary accommodation of visitors, of all artificial constructions . . . which would unnecessarily obscure, distort or detract from the dignity of the scenery.”

As a result of Olmsted’s arguments, out-going New York governor Lucius Robinson pledged his support in an 1879 statement to the New York State Legislature: “It is well known, and a matter of universal complaint, that the most favorable points of observation around the falls are appropriated for purposes of private profit, while the shores swarm with sharpers, hucksters and peddlers, who perpetually harass all visitors.” After a long campaign of petitions, newspaper articles, and editorials, the proposal was signed into law in 1883 by then-governor Grover Cleveland. Two years later on July 15, 1885, the Niagara State Reservation officially opened to the public, becoming the first state park established in the United States.

The campaign to change the face of Niagara Falls occurred as George Innes was in the midst of painting his various Niagara works. His inclusion of the billowing smokestack of the Bath Island paper mill seems to suggest this change. Scholars have debated its inclusion, some arguing that it is Inness commenting on the environmental implications of industrialization, while others believing that Inness simply painted what he observed. Innes would certainly have been aware of the very public ongoing struggle between those in favor of commercialization and those favoring preservation, a fight which played out almost daily in the newspapers. Given our knowledge as twenty-first century viewers of the damaging effects of pollution on the environment, it is easy to see how we could presume Inness was commenting on the increased industrialization of the Falls. Yet, we do not have any record from the artist himself on his position and how that may have affected his compositions.

Inness did take pen to paper describing the purpose of an artwork, which may shed light into his mindset: “A work of art does not appeal to the intellect. It does not appeal to the moral sense. Its aim is not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion. That emotion may be one of love, of pity, of veneration, of hate, of pleasure, or of pain; but it must be a single emotion, if the work has unity, as every such work should have, and the true beauty of the work consists in the beauty of the sentiment or emotion which it inspires.” At the very least, the smokestack reminds the viewer of the increasing industrialization of the United States as it neared the end of the nineteenth century.

Yellowstone: National Park

As cities, railroads, and steamships began to significantly change the appearance of the East, the need for public parks was more frequently expressed. Artist George Catlin was one of the first Americans to suggest the concept of a national park. In 1832, he wrote about his concern for the native populations, wildlife and wilderness, recommending that the American West might be preserved as “a Nation’s park . . . containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!” One of the earliest and most influential figures in the public parks movement was Andrew Jackson Downing, a gardener turned landscape architect, who in the 1840s successfully introduced nature into the domestic routine of the average American. Through his numerous and popular writings, Downing attempted to make the public more aware of the general characteristics of American scenery and to stress the moral and sociological benefits of a life lived in contact with nature. In his later writings he turned his attention to public parks, where he hoped people of all classes might enjoy themselves together. American authors, too, had proposed “national preserves” as a solution to the rapid growth of industry. In 1856 Henry David Thoreau wrote, “Why should we . . . have our national preserves . . . in which bear and panther, and some even of the hunter race, may still exist, and not be “civilized off the face of the earth” . . . for inspiration and our true re-creation? Or should we, like villains, grub them all up for poaching on our national domains?”

The Great Cañon and Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, Thomas Moran; Scribner’s Monthly, Volume 3, Issue 4, February 1872

When the members of the Hayden Expedition returned from surveying the Yellowstone in the early autumn of 1871, lead geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden mounted a campaign to protect the natural wonders he and his team had witnessed. He penned an article for Scribner’s Monthly titled “Wonders of the West II – More about the Yellowstone.” The article was accompanied by Thomas Moran’s sketches of the region (right). Soon, newspapers began reporting that a bill to make Yellowstone a national park was being considered by Congress. His efforts were bolstered by American financier and railroad magnate Jay Cooke, head of the Northern Pacific Railroad, and in the United States House of Representatives by Congressman William D. Kelley of Pennsylvania, where the Northern Pacific Railroad was headquartered. The Northern Pacific could look for plenty of business as people traveled west to visit the new park. Hayden enthusiastically championed the bill and found the compelling images from the expedition by Moran and Jackson of great help in his new cause. The sketches worked to convince citizens in the East of the wonder and majesty of the West.

In arguing for the case to preserve Yellowstone as a national park, Hayden cited Niagara Falls as an example of a natural wonder which had fallen to crass commercialization. Hayden warned, “If this bill fails to become a law this session, the vandals who are now waiting to enter into this wonder-land will, in a single season, despoil, beyond recovery, these remarkable curiosities, which have requires all the cunning skill of nature thousands of years to prepare. . . . [They will] make merchandise of these beautiful specimens, to fence in these rare wonders, so as to charge visitors a fee, as is now done at Niagara Falls, for the sight of that which ought to be as free as the air or water.” It is open to interpretation if Hayden meant that Yellowstone should be preserved specifically for ecological reasons, or if he simply meant that Yellowstone’s features should be preserved for recreational and scenic purposes. For instance, Mammoth Hot Springs had the same health benefits as similar spas in England, Germany, and Switzerland, which Americans had been visiting for years for health and recreation.

Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1871, William Henry Jackson, Library of Congress

To bolster support for the Yellowstone bill, Hayden had some of the “curiosities” from his travels exhibited in Washington, D.C. at the Smithsonian Institution and in the U.S. Capitol rotunda. William Henry Jackson’s photographs and Thomas Moran’s watercolors were presented by Hayden at numerous congressional committee hearings that winter as visible proof of Yellowstone’s wonders. Hayden also distributed copies of Scribner’s articles about Yellowstone illustrated by Moran. Decades later, photographer Jackson recalled that “the watercolors of Thomas Moran and the photographs of the geology survey [Jackson’s own] were the most important exhibits brought before the Committee.”

By February 27, 1872, both the Senate and the House had approved the Yellowstone park bill, which outlined that “the tract of land in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming, lying near the head of the Yellowstone river, . . . is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States, and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” On March 1, 1872 President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill into law, making Yellowstone America’s first national park. The bill specified it’s “regulations shall provide for the preservation, from injury or spoliation, of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and their retention in their natural condition. . . . [The Secretary of the Interior] shall provide against the wanton destruction of the fish and game found within said park, and against their capture or destruction for the purpose of merchandise or profit.”

Both the photographs of William Henry Jackson and the paintings and illustrations by Moran provided Congress with strong, persuasive images advocating the preservation of the region as a place of natural American wonders. The distribution of Moran’s print illustrations provided the American public with its first glimpse of the wonders of the West. These illustrations were effective pieces of propaganda for the preservation of the Yellowstone region, helping to convince Americans that the land was worth preserving in its natural state. Corps of Engineers Captain Hiram M. Chittenden wrote that Moran’s paintings and Jackson’s photographs “did a work which no other agency could do and doubtless convinced everyone who saw them that the regions where such wonders existed should be preserved to the people forever.”

Moran’s great painting Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone was completed the following month on April 28, 1872. He later wrote to Hayden, “I have been intending to write to you for some months past but have been so very busy with . . . designing & painting my picture of the Great Cañon that I could not find the time to write to anybody. The picture is now more than half finished & I feel confident that it will produce a most decided sensation in art circles.” Congress purchased the painting that same year for $10,000. Hayden wrote Moran in August that year proclaiming that “There is no doubt that your reputation is made [by the painting].” The memorable work both Moran and of photographer William H. Jackson in the summer of 1871 finally made people in the East believe the mythical wonders of Yellowstone Park.

Despite the passage of the Yellowstone Park bill as a milestone in the history of the environmental conservation movement, the bill was not passed for this purpose alone. Rather, the bill’s success was due to the region’s commercial potential and its abundance of exploitable natural resources. The bill does include language that would allow for the erection of buildings for the “accommodation of visitors” and the creation of “roads and bridle-paths therein.” The bill’s supporters consisted of interested parties, especially representatives of the Northern Pacific Railroad who stood to profit from the bill’s passage. In fact, a number of Northern Pacific railroad directors visited Moran in his studio prior of the official unveiling of the canvas. Moran wrote to Hayden that they were “decidedly enthusiastic about [the painting.]” To a degree, Hayden was acting in accordance with railroad interests. He assured Congress that because of the altitude, weather, and geography, the entire Yellowstone area could never serve any “useful” purpose – whether for mining, ranching, or farming. Consequently, preserving it as a national reservation would incur “no pecuniary loss to the Government.”

Yet as the nineteenth century progressed and our environment became better understood, the damage being done by civilized greed became more obvious. A strong conservation movement was established at the end of the nineteenth century, under the spiritual and political leadership of John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt. Muir wrote movingly about the High Sierras in California, the glacial formations and the magnificent trees, and, on occasion, with great distress about the conditions he witnessed:

In this glorious forest the mill was busy, forming a sore sad center of destruction, though small as yet, so immensely heavy was the growth. Only the smaller and most accessible of the trees were being cut. The logs, from three to ten or twelve feet in diameter, were dragged or rolled with long strings of oxen into a chute and sent flying down the steep mountain side to the mill flat, where the largest of them were blasted into manageable dimensions for the saws . . . by this blasting and careless felling on uneven ground, half or three fourths of the timber was wasted.

Primary Source Connections

Connect it with the Artwork: “Teaching with Documents: Letter from Thomas Moran to Ferdinand Hayden and Paintings by Thomas Moran.”

Act Establishing Yellowstone National Park, 1872

Act Establishing Yellowstone National Park, 1872

Read and Download the Document at Ourdocuments.gov

“One of the most imaginative and uniquely American responses to the endangered wilderness was the invention of the national park system. Ferdinand Hayden surveyed the area in 1871. Upon his return to the East, he mounted a campaign to promote, but also to protect, the natural wonders he had seen. He quickly wrote a well-received article for Scribner’s Monthly that included fellow expedition member Thomas Moran’s illustrations. He lobbied members of Congress by presenting them with an album of William Henry Jackson’s Yellowstone photographs. He was supported in his effort by Jay Cooke, the railroad magnate who anticipated increased tourist ridership on his lines serving the Yellowstone area. On March 1, 1872, Congress passed into law the act creating Yellowstone “a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”” – OurDocuments.gov

Artist Thomas Moran’s Diary, 1871

Read the Transcription and View the Diary at NPS.gov

“In 1871 the Hayden expedition set out to survey the sources of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, the area that was soon to become the nation’s first national park. Thomas Moran joined as artist of the team and depicted many of Yellowstone’s geologic features and landscapes. These depictions later proved essential in convincing the United States Congress to establish Yellowstone as a national park. During the forty days he spent in the area, Moran documented over 30 different sites. His sketches along with William Henry Jackson’s photographs captured the nation’s attention and forever linked the artist with the area. In fact, his name became so synonymous with Yellowstone that he was often referred to as Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran. Yellowstone National Park’s museum and archives collections include the diary of artist Thomas Moran. Moran’s diary has been transcribed.” – National Park Service

“Wonders of the West II – More about the Yellowstone.” Ferdinand V. Hayden, Scribner’s Monthly, Volume 3, Issue 4, February 1872

“Wonders of the West II – More about the Yellowstone.” Ferdinand V. Hayden, Scribner’s Monthly, Volume 3, Issue 4, February 1872

Download the Article (PDF)

This article, written by Hayden and illustrated by Moran, gave Americans one of their first glimpses of Yellowstone. While Hayden submitted his survey’s findings to Congress and had “curiosities” from the expedition displayed in Washington, D.C. for public consumption, this article was one of the first the American public would have seen on a widespread basis.

Frank Lecouvreur on Niagara Falls, May, 1868

Frank Lecouvreur on Niagara Falls, May, 1868

Read it at Archive.org (Excerpt from page 327)

Excerpt: “Tuesday, May the fourteenth, 1868. The grandeur of this natural wonder is not to be measured by the height of the cataract, but by the almost incredible mass of falling water which reaches one hundred million of tons in a single hour. . . . The impression this great wonder of Nature makes upon the beholder cannot easily be described. It is too grand, too overwhelming, to be expressed in human words. Only he, who has stood near the bottom and heard the indescribable roar and seen the stupendous volume of rushing waters, can even faintly grasp the idea of the Power and glory of his Creator, who tells him in an unmistakable voice: “Humble thyself, for all the works of this earth are mine. I am the Lord!” And once seen you will never forget Niagara Falls, nor the Voice which spoke to you.

Source: From East Prussia to the Golden Gate by Frank Lecouvreur, 1906, Josephine Lecouvreur, editor.

Literary Connections

Nature, 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Nature, 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Read and Download at Archive.org

In this essay, Emerson sets the foundation for Transcendentalism, that is, a philosophical movement in which writers in the 1820s and 1830s believed that the most important reality is one that is sensed and intuitive, rather than what is scientific knowledge. In the context of nature, transcendentalism suggests that this reality can be understood by studying and immersing oneself in nature. Emerson’s essay Nature seeks to demonstrate that the individual can develop a personal understanding of the universe through nature. Emerson’s system of ideas were closely related to that of landscape painters at the time. American painters combined what they observed with what they believed, capturing the divine essence in their landscape paintings. Emerson wrote, “Go out to walk with a painter, and you shall see for the first time groups, colors, clouds, and keepings, and shall have the pleasure of discovering resources in a hitherto barren ground, of finding as good as a new sense in such skill to use an old one.”

Table Rock Album and Sketches of the Falls and Scenery Adjacent, 1850

Table Rock Album and Sketches of the Falls and Scenery Adjacent, 1850

Read it at Archive.org

This resource serves as both a literary connection and a primary resource. A compilation of notations and poetry created by tourists (both American and international) at Niagara Falls, this book offers readers a unique glimpse of mid-nineteenth-century Americans’ response to spectacular natural beauty of the Falls. Below is an example of the poetry found in the book.

“Awestruck and lost in silent admiration,

I stand and gaze upon thy rushing waters,

Mighty Niagara, no sportive stream art thou;

Thy very thunder mocks such poor comparison,

And to my wildered ear, thy deafening roar

Makes my heart quail with its own littleness.

Oh, mighty grandeur! who can silent gaze

Upon thy verdant, angry foaming spray,

And not feel touched with the sublimity

Of such a scene. Magnificent!”

Artwork Connections

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1893-1901, Thomas Moran

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1893-1901, Thomas Moran

More than twenty years after his first journey to Yellowstone, Thomas Moran returned there in 1892 as the basis for another grand painting of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone which he would exhibit at the World’s Fair (also known as the Columbian Exposition) in Chicago in 1893. As in 1871, Moran’s friend the photographer William Henry Jackson was at his side making photographs as the artist drew. From his new drawings and watercolors, and presumably again drawing upon his earlier drawings and his personal collection of Jackson’s photographs, Moran assembled a larger and more broadly brushed painting. A comparison of the geological features of the 1872 painting with those in the 1892-1901 painting shows that Moran in 1892 was far more interested in light and color than in the precise shapes of rocks. He portrayed different weather conditions than he had previously, introducing a cloud burst over the distant falls that allows him to stress the atmosphere and mood more than specific details.

Niagara Falls, 1885, George Inness

Niagara Falls, 1885, George Inness

Niagara Falls is one of the most frequently painted and photographed landscapes in the United States. George Inness produced seven oil paintings of the falls during the 1880s and 1890s, more than he made of any other area at that time. By 1895, the area around Niagara Falls had become commercialized with many hotels, souvenir shops, and attractions. Inness wanted to reclaim the natural “terror and awe” of the falls, and so obliterated all evidence of bridges, hotels, and signs in his paintings.

The Great Horseshoe Fall, Niagara, 1820, Alvan Fisher

The Great Horseshoe Fall, Niagara, 1820, Alvan Fisher

Two scenes by Fisher (this painting and Fisher’s A General View of the Falls of Niagara) capture the thrill of visiting Niagara Falls, a site in upstate New York that quickly became a symbol of the continent’s epic scale and natural beauty. Tiny figures throw out their arms as if trying to describe to one another the vastness of what they see. Elegant tourists peer decorously across the chasm through opera glasses, while one young lady covers her ears against the stupendous noise. Reckless young men lie on their stomachs, daring one another to draw closer to the rock’s edge.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

Smarthistory’s “The Painting that Inspired a National Park”

“Approaching Research: Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

Glossary

Andrew Jackson Downing: (1815-1852) American landscape designer and proponent of public parks.

Calvert Vaux: (1824-1895) British-American architect and landscape designer. Along with Frederick law Olmsted, he is best known for his work on New York City’s Central Park.

chromolithographic reproduction: (or chromolithograph) a picture printed in colors from a series of lithographic plates (lithography is a method of printing from a flat surface).

Ferdinand V. Hayden: (1829-1887) American geologist, noted for his pioneering expeditions into the Rocky Mountains.

Frederic E. Church: (1826-1900) American landscape painter.

Frederick Law Olmsted: (1822-1903) American landscape architect. He is most well-known for designing New York City’s Central Park.

George Catlin: (1796-1872) American artist, traveler, and writer, best known for his portraits of Native American Indians.

Grover Cleveland: (1837-1908) 22nd and 24th President of the United States, previously governor of New York.

Henry David Thoreau: (1817-1862) American author and poet, best known for his work Walden (1854), a novel that is both memoir, social experiment, and a voyage of spiritual discovery. It is a reflection of a man’s experience living simply in nature, outside “civilized” society.

hydro-electric power: or hydroelectricity; generating electricity by conversion of the energy of running water.

Jay Cooke: (1821-1905) American financier and railroad magnate. Cooke’s firm financed the construction of the Northern Pacific Railway, which had a vested interest in seeing the Yellowstone park bill become law.

John Muir: (1838-1914) American environmental philosopher, author, and early proponent of wilderness preservation. Founder of the Sierra Club, a prominent conservation organization.

Louisiana Purchase: (1803) purchased from France during President Thomas Jefferson’s administration, the region of the United States encompassing land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains.

Meriwether Lewis: (1774-1809) American explorer, soldier, and politician. He is most well-known for his role in the Lewis and Clark Expedition, exploring the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase.

Nikola Tesla: (1856-1943) Serbian-American inventor, physicist, engineer. A one-time pupil of Thomas Edison. Tesla is best-known for his contribution to the alternating-current (AC) electrical system, still widely used today.

Northern Pacific Railroad: (or Railway) a transcontinental railroad which ran along the northern tier of the western United States, starting in Minnesota and ending at the Pacific Ocean in Washington state. Construction began in 1870 and was completed in 1883. The railroad’s main purpose was to ship goods like timber, wheat, minerals, and cattle to the East, while transporting prospective settlers to the West.

Pacific Railway Act: (1862) signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 1, 1862, this act provided Federal government support for the building of the first transcontinental railroad, which was completed on May 10, 1869.

Sanford Robinson Gifford: (1823-1880) American landscape painter, associated with the Hudson River School artistic movement.

Theodore Roosevelt: (1858-1919) 26th President of the United States, American statesman, explorer, and naturalist. Known for his reforms during the Progressive Movement and his strong support of ecological preservation.

Thomas Jefferson: (1743-1826) 3rd President of the United States, Founding Father, author of the Declaration of Independence, and American lawyer. Jefferson oversaw the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France and arranged for the exploration of that territory by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

Transcendentalism: a philosophical movement in which writers in the 1820s and 1830s believed that the most important reality is one that is sensed and intuitive, rather than what is scientific knowledge. In the context of nature, transcendentalism suggests that this reality can be understood by studying and immersing oneself in nature.

Ulysses S. Grant: (1822-1885) 18th President of the United States and commanding general of the Union Army during the Civil War.

Union Pacific Railroad: one half of the original transcontinental railroad, the Union Pacific was incorporated under the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 and signed into law by Abraham Lincoln. It was intended as a war measure during the Civil War. In 1869, it would join with its other half, the Central Pacific Railroad, at Promontory Point, Utah to connect the two railroads with a ceremonial “last spike,” also referred to as the “Golden Spike.”

William Henry Jackson: (1843-1942) American photographer, painter, and explorer of the American West.

William D. Kelley: (1814-1890) Member of the United States House of Representations from the state of Pennsylvania. He was one of the first Washington politicians to support the Yellowstone park bill.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 6 – The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

- Standard 1D – The student understands the effects of rapid industrialization on the environment and the emergence of the first conservation movement.

- 5-12 – Analyze the environmental costs of pollution and the depletion of natural resources during the period 1870-1900.

- 7-12 – Explain the origins of environmentalism and the conservation movement in the late 19th century.

- Standard 4B – The student understands the roots and development of American expansionism.

- 5-12 – Trace the acquisition of new territories.