Our earliest artwork pair enables us to discuss why people came to this country in the days before the American Revolution. What about America attracted them? In short, freedom and opportunity – basic rights that inspire today’s immigrants to this country. The two women pictured here both sought these things; the young Moravian girl journeyed with others of her faith to the colonies for religious freedom and for the ability to communicate their faith to others without fear of persecution. Mrs. George Watson’s ancestors emigrated earlier in the 17th century, in search of economic prosperity that would ensure the well-being of their family. As we move towards the third quarter of the eighteenth century, we come to learn about the effects of the American Revolutionary War on these women’s lives and on the communities in which they lived.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What information can we learn about Elizabeth Watson and life in the British colonies in 1765 from this painting? What clues does Copley give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Describe Mrs. Watson’s body language. How does the artist present her to the viewer?

- Standing straight, with a hand on her hip, Copley gives us a three-quarter length portrait or a woman who appears confident. Her body is turned slightly to the side, yet her face is turned towards us. Rather than looking off into the distance, she meets our gaze directly. Her forthright expression and set mouth seem to give us an impression of a person who is practical and sensible. Despite her wealth, she does not appear frivolous.

Mrs. Watson holds something very particular in her hand. What does it mean?

The exotic parrot tulip was not a flower that was native to the Colonies. The worldwide “tulip craze” drove the price of bulbs imported from Holland up to exorbitant costs. The small purple frittillaria flowers, once known for their medicinal qualities, multiply easily in the garden year after year. Together, these spring blooms tell us that Mrs. Watson keeps a cultivated garden for floral cuttings, a mark of sophistication. The shape of the imported vase echoes her own silhouette, and the delicate yet robust nature of the flowers refer to Mrs. Watson’s femininity, strength, and wealth.

Was does her attire tell us about her age, social class and economic status?

Elizabeth Watson wears a vibrant red silk sack back dress, a fashionable style from Europe in the 18th century. Bright colors were common among younger women; Elizabeth Watson was 26 years old in this portrait. Pearl-encrusted clips hold back her sleeves at the elbow, exposing the intricate lace detailing of her chemise (linen under-dress). Lace was expensive and imported, usually from Belgium or France, and was attached to the chemise as a cuff. The degree of detail in the lace and the number of layers would increase with social status. These details, combined with the extra length of white silk fabric that falls from the table and gathers in her right hand, indicate her status as the wife of a wealthy merchant and importer of fine European goods.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

The wife of a wealthy Boston merchant, Elizabeth Watson wears a fashionably gown of luscious satin and white lace and holds a porcelain vase that echoes the contours of her figure. The yards of expensive fabric and silk ribbons in the costume testified to George Watson’s success as an importer of European goods, as did the fact that he could afford to commission a portrait from Boston’s foremost painter, John Singleton Copley. Mrs. Watson showed herself to colonial society as a fashionable English matron, but her direct gaze suggests the grit and character of a new American society that would emerge within ten years.

Historical Background

Immigration to the American Colonies

Rapid immigration to the American colonies in the mid-eighteenth century nearly doubled the land occupied by colonists in the previous 150 years. Members of the Moravian Church, a Protestant denomination, helped to advance this fervent pace of immigration. The sitter in the portrait Young Moravian Girl likely immigrated to the colonies at this time. Originally from the historical Central European countries of Moravia and Bohemia (now part of the current day Czech Republic and Germany), the Moravians came to America for two important reasons: missionary work and religious freedom.

The height of Moravian persecution occurred during the Protestant Reformation, when Moravians and other Protestant reformers accused the Catholic Church of corruption and abuse of religious doctrine. The American colonies provided the Moravians with a safe haven to practice their faith and an opportunity to further their ecumenical and missionary efforts. Their missionary efforts extended as far as the West Indies and South Africa, making them the most active missionaries of the eighteenth-century. The Moravians began to migrate in waves from Germany to the American colonies in 1735. Emigrating with an established community ensured the Moravians greater success in the new world than other immigrants who came independently or with few resources. Moravians traveled in ships owned by their church, so they were not charged exorbitant prices for the passage. Additionally, journeying with community members and family provided stable emotional and physical support so that the practical needs of building a new community could quickly commence upon arrival in the colonies.

The Moravians settled in Pennsylvania, one of the most religiously-tolerant locations in the colonies thanks to the Quaker principles of William Penn. Their settlement, named Bethlehem, became a base of operations for the Moravian missionaries to help spread the word of God to the Native Americans through conversion to Christianity. The former Bishop of the Moravian Church Joseph Mortimer Levering wrote that, “the uncertainty of [the Moravians’] situation in Saxony [Germany] . . . might compel them to cross the ocean to find liberty and peace, and that such a settlement in Pennsylvania might then be not only a center of missionary operations but also a refuge for people leaving Bohemia and Moravia to seek freedom of conscience.” In order to emigrate, however, members of the community had to be given permission by community elders. The needs of the community were always placed above those of the individual and as such, elders considered the demographic needs of the missions first and not which individuals desired to go.

In contrast, the family of Mrs. George Watson, the former Miss Elizabeth Oliver, had been established in the colonies since the early seventeenth century. Her great-great grandfather had emigrated from London in 1632 and settled in Boston, Massachusetts. A surgeon by profession, he was likely attracted by the endless, untapped economic prospects the colonies offered. His future descendants would benefit from his emigration, as all would become successful merchants and politicians themselves or marry into other wealthy merchant families. Mrs. Watson’s father, Peter Oliver, spent his early life in business with his brother Andrew, importing wine and textiles before starting several businesses on his own and serving as a Massachusetts Superior Court Justice. The extravagant amount of silk fabric in the portrait of Mrs. Watson is likely a nod to both her father’s early success as a textile importer and her husband’s prosperous international trade business. Like his father-in-law, George Watson also practiced law in addition to his mercantile business. He was descended from a long line of successful merchants that came to the colonies from England in the 1630s and settled in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Women and Early American Community Life

The facet of Moravian life that bound the community together like no other was their dedication to missionary work; the Moravians were the most active Protestant missionaries of the eighteenth century, sending community members to the West Indies, South America, and as far as South Africa. By 1760, the Moravians had sent out 226 missionaries and baptized more than 3,000 converts, including American Indians. In North America the key undertaking for Moravian missionaries was to convert the Indians to Christianity. The Moravians viewed the Indians as heathens in need of spiritual enlightenment and guidance. Some missionaries even went to live among the Indians in order to learn their languages and to minister to individual members of the native population. The Moravian community of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania became the center of all North American Moravian missionary activity, providing economic support and material resources for all outlying Moravian missions.

One of the most distinctive features of Moravian community life was the Choir System. People were separated into “choirs,” or groups, based on their age, gender, and marital status. It was believed that individuals of like age and gender were best prepared and able to encourage each other’s religious growth. Members of the same choir ate, worked, worshiped, slept in dormitories, and attended school together. This communal living arrangement was intended to strengthen the unity of the society as members had to rely on choir-mates for support rather than their siblings or parents. The names of the choirs reflected the sex, age and marital status of those in the choir, such as the “Older Boys’ Choir,” ages 12-19 or the “Single Sister’s Choir,” age 19 until marriage.

All work performed by the Moravians during the pre-Revolutionary War years operated under a system known as the “General Economy,” in which all goods or money produced was considered the property of the community, not the individual. Under this system there was no private wealth or housing, nor any privately owned businesses. Every member’s contribution was collectively pooled and in exchange, necessities such as food, shelter and clothing were provided. Marie Minier, a Single Sister in the Bethlehem community, praised the General Economy in 1750 stating that, “For 12 years now I have enjoyed the care [of the General Economy] and eaten from one bread and been clothed, all of which to this hour has been great and of importance to me. I . . . accept things the way the Brethren do things, for it is a wonder to me daily that He has maintained so large a community, and we cannot say that we have ever gone without.” For single women like Marie Minier, the General Economy system afforded them relative security and independence; single women who chose not to marry did not need to rely on a father or brother for financial support, nor worry about becoming a financial burden. In other parts of eighteenth-century America women who did not marry would have been socially and economically excluded, dependent on their fathers or male family members. Yet by the 1760s, the system of communal property began to wear on the younger generations of ambitious Moravians who saw that in other communities hard work was rewarded with personal financial gain. In 1762, the General Economy was abolished in favor of self-owned and operated small businesses and private family homes.

Portrait of Lucy Parry, wife of Admiral Parry, 1745-49, John Wollaston, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The relative freedom which Moravian women enjoyed contrasted sharply with the structured, subservient life led by women like Mrs. George Watson, the former Miss Elizabeth Oliver. While Moravian women could choose not to marry if they wished, this was not an option for women of Mrs. Watson’s position, who were completely governed by either their father or husband. Marriages were always arranged, as was the case with Elizabeth Oliver’s marriage to George Watson in 1753. These dynastic patterns of marriage were financially, socially or politically motivated, meant to retain wealth and influence within a certain strata of society. In Watson, Elizabeth Oliver’s politically-powerful father Peter gained a son-in-law with similar political leanings and access to a vast network of trade routes, merchants and overseas contacts. In return, George Watson gained not only a young bride able to provide him with children, but connections through his father-in-law that could expand his import/ export business. Often portraits were commissioned to celebrate these dynastic marriages, as was the case with another portrait in the Museum’s collection of Mrs. Lucy Parry (right), wife of British Navy Admiral William Parry. By crafting these marriages the social elite began to produce a colonial equivalent of the English gentry. Over time, this strategy would enable them to consolidate and protect power among their small, elite group.

Popular pamphlets of the day stressed that a woman’s service to her family and to her husband were of the utmost importance in her life. This differed greatly from Moravian women, whose chief duty was to their community and God, not to their family, husband, or self. Since Moravian women worked jobs benefitting the larger community, they were freed from traditional familial duties and were able to sample more freedom than women in Mrs. Watson’s position.

The Role of Portraits in Colonial America

Robert Hooper, 1770-72, John Singleton Copley, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Portraits served an important role in colonial society, whether that society was rural Bethlehem or cosmopolitan Boston. Portraits provided important information about the individual, such as their social and economic status or religious affiliation. Portraits were luxury items, not necessities, and therefore by simply owning a portrait the owner was designated as an individual of means. The placement of the portrait within the home, usually in the entry parlor, would announce the social status of the residents to all who entered the home. These status symbols were often commissioned to celebrate occasions like marriages or the inheritance of an estate. Portrait compositions often included personal possessions which further indicated the sitters’ wealth and status, such as the imported vase and exotic tulip. Both of these could only have been purchased by an elite few, acquired through costly importation.

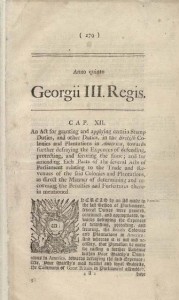

It can also be speculated that the portrait of Mrs. Watson acted as a subtle, yet effective, political statement in view of its historical context. The same year the portrait was painted, 1765, Britain imposed its first direct tax on the colonies, the Stamp Act. Taxing its colonies was England’s solution to paying the debt incurred during the French and Indian War (1756-1763). In protest, political activists organized a non-importation movement which called on colonists to boycott all British goods, giving up all imported luxuries and finery and to thoroughly embrace austerity. The imported English porcelain vase, exotic tulip flower and abundance of expensive silk indicate to the viewer that this is a woman not embracing austerity, but flaunting her many non-native goods. This notion is supported by the fact that the Watson and Oliver families were publicly known to be extremely loyal to the English crown. It was said that “[King] George III had no more able or zealous friends in America than the Olivers.”

Mrs. Watson’s ostentatious presentation is worlds apart from her demure counterpart, the young Moravian girl. As a community that embraced simple living and rejected material possessions, why then do portraits of Moravian community members exist? The answer lies with the artist, John Valentine Haidt, and the role of art in the Moravian community. Haidt’s involvement with the Moravians began in 1746 when he converted to the religion and began working as a preacher in the community. During a period of religious turmoil Haidt, a former goldsmith with formal artistic training, felt that he could better communicate his religious teachings by painting rather than preaching. Haidt advocated for his new position writing, “I thought, if [the Moravian people] will not preach the martyrdom of God anymore, I will paint it all the more vigorously.” In this new role, Haidt was chosen to relocate to Bethlehem as the official Church painter.

Haidt’s occupation as a painter was considered a religious undertaking. This concept derived from the fact that each member of the community fulfilled a labor which they considered a calling from God. As a result, portraits, or images of faith, were not thought of as records of individuals nor of their worldly accomplishments, unlike the portrait of Mrs. George Watson. Comparable to all aspects of Moravian life, even portraits were considered religious, for they functioned as outward extensions of faith, communicating piety and reverence. It is for this reason that Haidt’s Moravian portraits were considered religious art just as much as his images of Biblical scenes. This also helps to explain why so many of Haidt’s Moravian portraits were never recorded with the name of the individual depicted. That the young girl’s name and identity is unknown to us makes her an all-the-more fitting foil to Mrs. Watson, for she is symbolic of the unpretentiousness and simplicity of her community.

Road to Revolution

Several pivotal events occurred which set the colonies on a course for revolution and emboldened colonists to declare their independence. The events that transpired irrevocably altered the lives of the individuals who lived through them, no matter which side of the cause they supported. In the following sections, we will explore how these events transpired in two different regions of colonial America, Boston and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, represented by Mrs. George Watson and Young Moravian Girl, respectively.

England found itself in a predicament in the aftermath of the French and Indian War. The high costs of war and maintaining continued military presence in North America had plunged the country into a staggering amount of debt. In an effort to raise money the English Parliament imposed a variety of taxes on the colonies, attempting to control the trade in and out of the region. These taxes angered the colonists, but perhaps none more so than the Stamp Act of 1765 which required that most printed material in the colonies be printed on specially stamped paper produced in Britain. The printed material, which had to be paid for in British currency, included newspapers, magazines and legal documents. In protest the colonists adopted a non-importation boycott of British-made goods in 1765, the same year Mrs. George Watson’s portrait was painted.

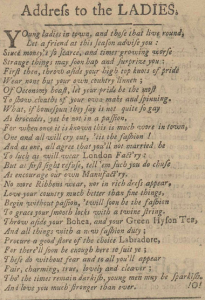

Many women chose to wear dresses made of home-spun cloth instead of those made of imported textiles to show their support for the non-importation boycott and to protest British taxation. The abundance of luxurious imported silk fabric in Mrs. Watson’s portrait supposes that her loyalties remained with Great Britain by flaunting costly imported goods and ignoring the non-importation boycott. While no record exists which reveals Mrs. Watson’s personal inclinations, a woman’s political loyalties were often dictated by those of her husband or her family. As both Mrs. Watson’s husband and father were prominent, outspoken Loyalists, it can be inferred that her political allegiances, at least publicly, were the same.

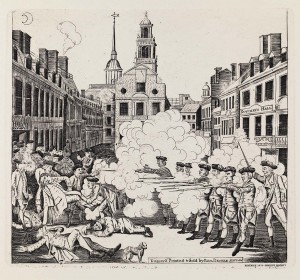

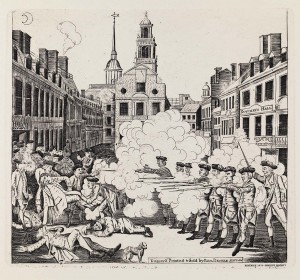

The Bloody Massacre, original 1770, restrike 1970, Paul Revere, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Boston became increasingly dangerous as revolutionary activity intensified. Colonists were angry with Great Britain for the newly imposed taxes, and furious about the British soldiers sent to the colonies to make sure those taxes were enforced. Tensions over their presence erupted on the night of March 5, 1770, when a mob of unarmed colonists provoked a group of British soldiers standing guard outside the customs house, hurling insults and snowballs. As tensions rose, the British soldiers discharged their weapons, killing five men and wounding many others. This event would become known to history as the Boston Massacre.

This incident presents us with a direct example of the lives of Mrs. Watson and her family colliding with the events that led to revolution. The British soldiers involved in the incident were arrested and charged with manslaughter. The desire by Bostonians for an immediate trial was so intense that court was convened a week after the incident. One of the key players in the trial was a then-relatively unknown lawyer named John Adams. Although he sympathized with his fellow colonists, the future president agreed to defend the British soldiers. Several judges were tasked with presiding over the trial, one of whom was Elizabeth Watson’s father, Peter Oliver.

The role Oliver had to play in presiding over the fate of the British soldiers did not endear him to the people of Boston and the pressure to find the prisoners guilty was immense. Some of the judges even feared for their personal safety. Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson wrote in a letter at that time that he “found it difficult to prevail upon three of the judges to sit at the trial for fear of losing their popularity. . . . I have persuaded Judge Lynde, who came to town with his resignation in his pocket, to hold his position a little longer. . . . Judge Oliver appears to be firm, though threatened in yesterday’s paper.” After almost three hours of deliberation, the jury sided with the defense and the soldiers were acquitted of murder.

After the trials, Governor Hutchinson was so pleased with Peter Oliver’s work, that he appointed him Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court. Oliver’s Loyalist connections and outspoken support for the Crown no doubt aided in his appointment; it was said that “[King] George III had no more able or zealous friends in America than the Olivers.” However, Oliver’s good fortune did not last long, for once the public knew that part of his salary as Chief Justice was paid by the English crown, juries refused to serve under him and he was later impeached by the Massachusetts House of Representatives. His popularity and reputation quickly plummeted, coinciding with the outbreak of war. Fearing for his life, yet refusing to renounce his Loyalist sympathies, Oliver eventually fled to England in 1776. Years later he wrote a scathing, bitter account of the Patriots, their “rebellion,” and of his personal experiences during the war.

Loyalists like Peter Oliver and his son-in-law George Watson tended to have longstanding economic and social ties with British merchants and government officials. They were often intermarried with British families, creating stronger ties with England. Their very livelihoods depended on their good relationships with fellow merchants willing to trade with them across the Atlantic. As a result of these numerous interwoven connections, merchants like George Watson had everything to lose if they chose to side against England.

Another Loyalist merchant with strong ties to England was Richard Clarke, Boston’s second largest importer of tea. Clarke also happened to be the father-in-law of John Singleton Copley, the artist who painted Mrs. George Watson, as well as Mrs. Watson’s maternal uncle. In 1773 the English Parliament passed the Tea Act in order to bolster the East India Company, which was drowning financially in a sea of surplus tea. The act gave the company a monopoly on all of the tea sold in the colonies, relieving them of export taxes on the tea while also asserting Parliament’s authority to tax its colonies. Realizing he could not compete with the monopoly on his own, Clarke, along with other Loyalists, bid on and won a contract to receive a consignment of the company’s tea to import to the colonies. Colonists were outraged, believing that the duty on tea imposed by the Townshend Acts was an unconstitutional abuse of England’s power and that the tea consignees were just as culpable. Angry protesters mobbed the homes of Clarke and his family, including John Singleton Copley, demanding Clarke’s resignation as a consignee. Clarke initially refused, calling the group “chiefly . . . of the lowest rank.” Other demonstrators took matters into their own hands on the night of December 16, 1773, when they boarded ships in Boston Harbor loaded with the consignees’ newly imported tea and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water, an event later referred to as the Boston Tea Party. Of the event, John Adams would write that “This is the most magnificent Movement of all . . . There is a Dignity, a Majesty, a Sublimity, in this last Effort of the Patriots, that I greatly admire. . . . The People should never rise without doing something to be remembered – something notable And striking. This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cant [sic] but consider it as an Epocha in History.”

The loyalty of those who remained devoted to the Crown was recognized with positions of importance and a substantial income. George Watson’s loyalty was rewarded in August of 1774 when he was appointed by newly-installed British military governor, General Thomas Gage to the prestigious Mandamus Council, an advisory body which was formed after the English Parliament had passed the Massachusetts Government Act. This act, one of the five Intolerable Acts, replaced the Massachusetts government charter of 1691 with a new restricted one, effectively stripping the colonists of self-governance. The act was intended to punish the colonists for their role in the Boston Tea Party. Elizabeth Watson’s brother noted the appointment in his diary on August 23, 1774, “Well Col. Watson is sworn in to be one of His Majesties Council . . . The first Sunday [after his swearing in, the townspeople] passed him in the street without noticing him which occasions him to be very uneasy.” That same day, after he had taken his seat in Church, his neighbors and friends “put on their hats before the congregation and walked out of the house. The extreme public indignity was more than he could bear. As they passed his pew, he hid his face by bending his head over his cane.” Watson even received letters threatening to tar and feather him if he was ever seen in Boston.

The anger and disappointment of the townspeople was so strongly felt that George Watson was compelled to resign his position. Writing to General Gage a mere seven days after he was appointed, Watson explained:

By my accepting of this Appointment, I find that I have rendered myself very obnoxious, not only to the Inhabitants of this place, but also to those of the neighboring Towns. On my Business as a Merchant I depend, for the support of myself and Family, and of this I must be intirely [sic] deprived, in short, I am reduced to the alternative of resigning my Seat at the Council Board, or quitting this, the place of my Nativity, which will be attended with the most fatal Consequences to myself, and family. Necessity therefore obliges me to ask Permission of your Excellency to resign my Seat at the Board, and I trust, that when your Excellency considers my Situation, I shall not be censured.

George Watson’s personal associations did little to quell the public’s disapproval. One of these associations which created a particular firestorm was his friendship with artist John Singleton Copley. As the preeminent portrait painter to the wealthy in pre-Revolutionary War New England, Copley was sought after, by Loyalists in particular, for his adherence to English style and portraiture conventions. Additionally, Watson was connected to Copley through their shared political views and familial ties; Copley’s wife Sukey was first cousins with Watson’s wife, Elizabeth. Two years before Elizabeth Watson’s death, her husband had commissioned this elegant portrait from Copley.

A visit from Watson to Copley’s home in 1774 incurred the wrath of an angry mob. In a letter to his brother-in-law, Isaac Winslow Clarke, Copley described the incident:

A number of persons came to the house, knock’d at the front door, and awoke Sukey and myself. . . . they asked me if Mr. Watson was in the house. . . . I told them he had been here, but he was gone . . . they than [sic] desired to know how I came to entertain such a Rogue and Villin [sic] . . . they said they could take no mans word, they believed he was here and if he was they would know it, and my blood would be on my own head if I had deceived them; or if I entertained him or any such Villain for the future . . . what if Mr. Watson had stayed (as I pressed him to) to spend the night. I must either have given up a friend to the insult of a Mob or had my house pulled down and perhaps my family murthered [sic].

Other Loyalist families endured similar harassment; heckling crowds, damage to homes and property, and threatening letters. Mrs. Watson’s own uncle, Andrew Oliver (1706-1774), was the Massachusetts official responsible for implementing the provisions of the Stamp Act. For this, his image was hanged in effigy by protestors, who later looted and destroyed his home. Fearing for his life, he asked to be relieved of his duties and publicly resigned underneath the Liberty Tree, the same tree from which he was hanged in effigy.

John Singleton Copley quickly realized that Boston was no longer safe for those who supported Britain. Two months after the incident involving Watson, Copley and his family, including his father-in-law Richard Clarke, fled to London. There, the artist was well-received by British society. He soon joined the Royal Academy of Art and in 1785 was commissioned to paint a group portrait of the three youngest daughters of King George III. Copley would never again set foot in America. It has been estimated that approximately 80,000 Loyalists (of a total population of about 2.1 million) left America during the period of the Revolutionary War, with many fleeing to Britain and Canada.

The Effects of War

Young Moravian Girl, 1755-60, John Valentine Haidt, Smithsonian American Art Museum

In the years before the American Revolution, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania was a quiet enclave, recognized for its ample accommodations, good music, friendly people and excellent food and drink. Despite being a “closed community,” Bethlehem was well-known for its hospitality to travelers. It was in these pre-war years that future prominent revolutionaries like George Washington and John Adams became acquainted with the town, its ample facilities and, most importantly, its inland location. Bethlehem was a good distance from the center of the early revolutionary activity in Boston, yet the town would become a key strategic location for the Continental Army. In an effort to counter English military efforts to control the seas and colonial port towns, American forces waged guerrilla warfare by moving frequently, maintaining interior lines and controlling essential routes of communication and trade. Bethlehem was positioned at a key interior point along these routes, thereby making it a very valuable asset for the Continental Army.

The Moravians were well aware of the revolutionary storm brewing, and with the impending onset of war their pacifist community faced a moral dilemma; how were they to uphold their principles of non-violence while facing increasing pressure from other colonists to fight? Many Moravians sympathized with the colonial cause but others hesitated in their support, wary of the moral implications of war and revolution. Rhode Island Congressman William Ellery visited Bethlehem at this time and wrote of their moral dilemma: “Their people, like the Quakers, are principled against bearing arms, but are unlike them in this respect, they are not against paying such taxes as government may order them to pay towards carrying on war, and do not, I believe, in a sly, underhand way, aid and assist the enemy, while they cry peace.” In 1791 Moravian community leader John Ettwein recalled a conversation with Alexander Hamilton during the war in which he expounded the Moravians’ pacifist creed: “Mr. Hamilton asked me about our principles with regard to war and asked whether it was a point of Moravian doctrine to do no military service. I told him it was not a point of doctrine . . . Ever since [Jan] Hus’ day, the Brethren separated themselves from the others who waged war . . . and agreed to make one of their principles or rules not to fight with carnal weapons but with prayer.”

The community was divided along generational lines with younger men willing to take up arms in the name of patriotic duty and older men holding steadfast to their traditional pacifist beliefs. One community elder felt that even paying the fine for not bearing arms was “equivalent to murder and paying for a substitute.”

After news of the Battle of Lexington broke in April of 1775, the public’s unfavorable perception of the Moravians intensified as the pacifist community had yet to proclaim their position. The Moravians were forced to release a public declaration that they “desired the good of the country and had no intention to place themselves in opposition to the course of events, they claimed the liberty given them in all countries of exemption from military service, but would willingly bear their part of the public burden otherwise.” Not everyone was convinced that the Moravians had not secretly sided with the British; some in colonial military service deemed the community a “Tory nest” that “ought to be burned down.” This however was not the majority, and other American troops passing through Bethlehem on their way to Boston learned firsthand that the Moravians were not dangerous, nor traitorous, and even took the opportunity to attend church services offered by the community.

The negative opinion of the Moravians quickly dissipated when the community became a vital resource for the Continental Army. After the disastrous Battle of Fort Washington, Moravian leaders agreed to house the General Hospital of the Continental Army in Bethlehem. As a key strategic position outside the main areas of disturbance, the adaptation of Bethlehem into a hospital and way station was an ideal compromise for the Moravians; the arrangement did not compromise their religious principles and the task of caring for the sick and wounded appealed to their sense of humanity in a way that was in accordance with their character and religious mission.

The Moravians did, however, have reservations about how the army hospital would affect their way of life. It was suggested that for the time being, the Moravians of Bethlehem could move to a nearby Moravian settlement, but community leader John Ettwein wrote to George Washington on May 25, 1778 explaining the injurious nature of this move, claiming that “souls would be inexpressibly distressed” and that the people would “be entirely ruin’d [sic] in their Property, their useful Occupations.” Washington, while sensitive to the community’s concerns, responded to Ettwein three days later explaining how vital Bethlehem was to the Continental Army, assuring “that the public good be effected [sic] with as little sacrifice as possible of individual interests.”

As Bethlehem transformed into a hospital, the town was visited by such notable travelers as Samuel and John Adams (in January, 1777) and John Hancock. However, one notable visitor would arrive as a patient; the Marquis de Lafayette. The Marquis was brought to the town on September 21, 1777 after sustaining a leg wound in the Battle of Brandywine ten days earlier. Lafayette was taken to the house of the Moravian farm superintendent to recuperate and was looked after by the farmer’s wife and daughter. Writing to his wife from Bethlehem, Lafayette described his wound:

The surgeons are astonished by the rate at which it heals; they are in ecstasy every time they dress it, and maintain that it is the most beautiful thing in the world. I myself find it very foul, very tedious, and rather painful; there is no accounting for tastes.” Of the Moravian community he wrote, “I am at this moment in the solitude of Bethlehem . . . This establishment is truly touching and very interesting. The people here lead a gentle and peaceful life.

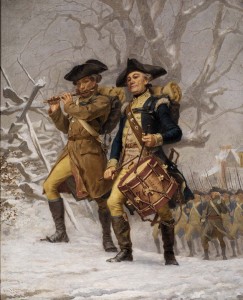

The Continentals, 1875, Frank Blackwell Mayer, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Lafayette recuperated in Bethlehem through the month of September, 1777. That same month word came from Philadelphia that George Washington and his troops had to fall back from Philadelphia. In advance of the expected British occupation, an exodus of civilians and soldiers left Philadelphia and marched sixty miles north to Bethlehem, seeking shelter, medical treatment and supplies. By the next month, over 400 soldiers were lodged in the single men’s house, with many more sheltering in tents at the rear of the building. One contemporary account recalled that 700 wagons containing munitions and baggage, including the personal luggage of General George Washington, arrived accompanied by 200 soldiers. Space became increasingly limited with a growing number of sick, wounded and displaced.

Conditions at Bethlehem worsened by the winter of 1777; resources quickly depleted with the large amount of people needed to be fed and cared for, and other basic supplies like clothing were in short supply. Moravian women were forced to empty out chests and drawers in an effort to make suitable bandages and bed coverings and reported that, “Three or four times we begged blankets from our people for the soldiers and distributed them to the needy; likewise shoes and stockings and old trousers for the convalescents whose clothing had been stolen in the hospital, or who had come into it with nothing but a pair of ragged trousers full of vermin.” Another account paints a horrifying picture of the deteriorating conditions at the hospital:

The condition of things in the hospital became appalling towards the close of the year 1777 . . . the number of patients had increased beyond the facilities of the staff of physicians and surgeons to properly care for them, when additional wagons loaded with suffering men began to arrive after the battle of Germantown . . . some of these newly-arrived ones were laid upon the ground in the rain to die. . . . The Brethren’s House, especially the crowded and unventilated attic-floor, had become a reeking hole of indescribable filth. . . . A malignant putrid fever broke out and spread its contagion from ward to ward. The physicians were helpless and the situation became demoralized. Men died at the rate of five, six and even a dozen during one day or night. The carpenters and laborers of Bethlehem were not asked to make coffins and help bury the dead, as in the previous winter. This was now done by the soldiers, as quickly and secretly as possible . . . . At the dawn of day, a cart piled full of dead bodies would be seen hurrying away from the door of the hospital to the trenches on the hill . . . Unnamed and unnumbered they were laid, side by side, in those trenches.

Relief for the Moravian community came the following April, in 1778, when Washington ordered the removal of the Continental Army hospital from Bethlehem. After a cleansing and re-dedication of the former hospital, Moravian life gradually achieved normalcy; the single men moved back into the Brethren’s House which had been the hospital, trade slowly came to back and life returned to its pre-war character. As a result of the war, community elder John Ettwein wrote in January, 1778, “We have suffered considerably as to our property; yet that is quite healthy, for it counteracts the corrupted spirit which seeks to acquire surplus possessions.” He also vowed to “do nothing either directly or indirectly against the United States. . . . As long as we are protected we will pay Taxes & bear our Part of the public Burthen [Burden], as far as we are able.”

George Washington was always grateful to the Moravian community for their aid during the war, and continued a friendly correspondence with leaders of the community long after the war had ended. As president, Washington was especially appreciative of the Moravian’s mission to convert to Christianity the Native American Indians, specifically the Lenni-Lenape tribe of Pennsylvania. Washington wrote to the Moravian community leaders, “Be assured of my patronage in your laudable undertakings. . . . [It is] a desirable thing for the protection of the Union . . . to civilize and Christianize the Savages of the wilderness.” In the end, the impact that the Moravians had in transforming their community into a way station and an army hospital proved immensely more valuable to the American cause than if they had sent a handful of their men into battle. Despite having reservations about the war in the beginning, the majority of Moravians post-war felt that the American victory had been preordained by God and had therefore been justified.

Primary Source Connections

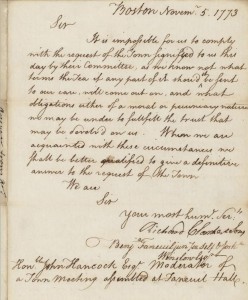

Letter to Boston Town Meeting by Richard Clarke, concerning his shipment of tea. Boston, November 5, 1773.

Letter to Boston Town Meeting by Richard Clarke, concerning his shipment of tea. Boston, November 5, 1773.

Read the letter on Archive.org

Richard Clarke, the father-in-law of portrait painter John Singleton Copley (and maternal uncle of Mrs. George Watson) was a consignee of the tea that was dumped into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773. In this letter, written just one month prior to the Boston Tea Party, Clarke writes that he is unable to refuse his tea shipment from the East India Company. Clarke’s mercantile firm was particularly obstinate in refusing to halt the importation of English tea to the colonies.

The Stamp Act, 1765

Read the transcription or View the Original Document

“The Stamp Act, which taxed Americans for stamps imprinted on a wide variety of legal and official documents, was the first measure passed by the British parliament to arouse widespread antagonism in the thirteen colonies. Taking effect on November 1, 1765, it was considered by both British and American leaders as a precedent-setting measure because of the important point it established, the right of parliament to lay an internal tax upon the colonies.” – Library of Congress

“Address to the Ladies,” November 16, 1767, The Boston Post-Boy & Advertiser

Read the transcription at the Massachusetts Historical Society

“As managers of the household budget, women are integral to the colonial economy. Their everyday activities, such as purchasing clothing and food, make them essential participants in politicians’ attempts to curb the consumption of British goods. Patriotic daughters of liberty are urged to find local substitutes for imported articles, especially those imported from Britain. Many propagandists encourage women to join the non-consumption movement by connecting the politics of boycotts to the security of the home and family.” – Massachusetts Historical Society

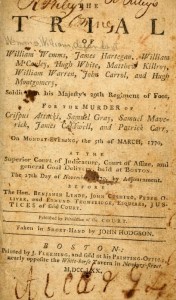

Transcript of the Boston Massacre Trial, March 5, 1770.

Transcript of the Boston Massacre Trial, March 5, 1770.

Read it on Archive.org

Printed in 1770, this is a transcript of the Boston Massacre Trial, in which British soldiers were accused, a later acquitted, of the murder of five Boston civilians. Distributed by the Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature. Printed by J. Fleeming, 1770.

Additional Primary Sources:

Letter written by artist John Singleton Copley, about Mr. George Watson, 1774

Download a Transcription (PDF)

Letters and Papers of John Singleton Copley and Henry Pelham, 1739-1776; 1914; Massachusetts Historical Society

Read the Google e-Book

Selected letters written by the Marquis de Lafayette about Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1777

Download a Transcription (PDF)

Literary Connections

Poetry:

America, A Prophecy, 1793, William Blake

Read it at Poets.org

“The American revolutionary moment inspired—and continues to inspire—a vast body of literature, much of which, like Blake’s poem, attempts to allegorize the fledgling nation’s birth and cast its genesis in the language of archetypal struggles and timeless human themes. America, a Prophecy is in some sense typical of early writings about American independence, which often strive to romanticize the clash between colony and king, rebellious sons and overbearing father.” – Poets.org

“To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth” 1772, Phillis Wheatley

Read it at Poets.org

Phillis Wheatley was the first published African-American female poet. She was brought to America as a slave in 1761, but was freed when her pro-revolutionary writings gained popularity in the colonies. This poem reflects her hope that the Earl of Dartmouth would be an ally to the colonists, for he had previously openly opposed the Stamp Act. Wheatley writes that her love of freedom comes from being a slave. She compares a slave’s relationship with a slaveholder, to the colonies’ relationship with England.

“Paul Revere’s Ride” 1860, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Read it at Poets.org

One of Longfellow’s best known and most widely read poems, “Paul Revere’s Ride” was published on the eve of the Civil War and helped turn a relatively obscure figure in Revolutionary history into a national folk hero.

Fiction:

Grades 7-10: Five 4ths of July, 2011, Pat Hughes – Grades 7-10

Grades 7-10: Five 4ths of July, 2011, Pat Hughes – Grades 7-10

Find it in a Library

“On July 4th, 1777, Jake Mallory and his friends are celebrating their new nation’s independence in a small coastal town in Connecticut. Fourteen-yearold Jake wants nothing more than to get out from under the strict thumb of his father and see some adventure. But he learns too late that he must be careful what he wishes for. Over the course of four more 4ths, he finds himself in increasingly adventurous circumstances-from battling the British army to barely surviving on a prison ship to finally returning home, war-torn and weary, but hopeful for his and America’s future.” – Goodreads.com

Grades 7-10: My Brother Sam Is Dead, 1974, James Lincoln Collier and Christopher Collier

Grades 7-10: My Brother Sam Is Dead, 1974, James Lincoln Collier and Christopher CollierFind it in a Library

Artwork Connections

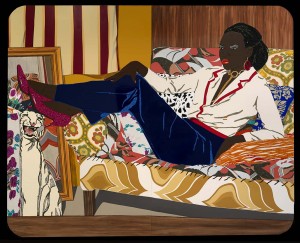

Portrait of Mnonja, 2010, Mickalene Thomas

Portrait of Mnonja, 2010, Mickalene Thomas

Mickalene Thomas’ work explores notions of beauty, sexuality and black female identity. Her use of rhinestones and vivid textile patterns adds an even greater sense of drama and sensuality to her paintings. For Thomas, the rhinestones evoke folk art traditions and Haitian voodoo art. They also serve as a metaphor for female beauty products, which can both enhance and mask a woman’s identity. The reclining figure is posed in a sassy contrapposto and situated against a wood-paneled background redolent of a seventies-era living room. Her right hand rests on her knee, revealing nail polish that matches her audacious pink heels. She exudes dignity and self-assurance.

Robert Hooper, 1770-72, John Singleton Copley

Mr. Hooper was the son of Robert King Hooper, who owned a fishing fleet that worked out of Marblehead, Massachusetts. The younger man already sports the rotund physique that Copley had captured in a portrait of Hooper’s father years earlier. Behind him, the sea, visible through an open window, recalls the source of his family’s riches. Robert had graduated from Harvard in 1763, and Copley’s painting shows him settling into the comfortable life of a merchant prince. Copley owed his living to this new class, whose wealth supported the artists, writers, and educators of the colonies. He had joined the elite not long before, through his marriage to Susanna, daughter of Richard Clarke, consignor of the tea dumped during the Boston Tea Party.

Portrait of Lucy Parry, Wife of Admiral Parry, 1745-49, John Wollaston

Portrait of Lucy Parry, Wife of Admiral Parry, 1745-49, John Wollaston

The demand for formal portraiture in the homes of land owners and merchants grew as their prosperity grew. The portrait of Lucy Parry displays the prosperity of this growing class of landowners. Born in England, Lucy Parry came from a family long associated with the British Royal Navy. Her father was a commodore who served in the West Indies and her husband, Admiral William Parry, became commander-in-chief of several Caribbean islands, including Jamaica.

Polly Ouldfield of Winyah , ca. 1761, John Hesselius

, ca. 1761, John Hesselius

Polly Ouldfield was born into a life of privilege. Her father was a member of the Commons House of Assembly in London, and records indicate that he owned land in Georgetown in 1752. Polly’s husband was a landowner from Charleston, South Carolina, who served as Commissary of Militia in the Georgetown District during the Revolutionary War. In this portrait the landscape beyond the window suggests the Ouldfields’ significant landholdings, and Polly’s luminous, lace-trimmed silk dress embellished with decorative pearls also conveys the richness of planter society.

The Bloody Massacre, original 1770, restrike 1970, Paul Revere

The Bloody Massacre, original 1770, restrike 1970, Paul Revere

Produced just three weeks after the Boston Massacre, Paul Revere’s engraving is one of the most effective pieces of propaganda in American history. Revere based his engraving on that of engraver Henry Pelham, John Singleton Copley’s half-brother, who created the original version. Pelham was neither paid nor credited for his work, but it is Revere who is remembered for the print as his version went out to the masses first.

The Continentals, 1875, Frank Blackwell Mayer

Two months after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Battle of Bunker Hill took place just outside of Boston. This image depicts Continental Army soldiers on their way to that battle, marching through the snow to the beat of a drum and the sound of a flute. The snow-covered woodland landscape would have been a similar setting when the Continental Army arrived at Bethlehem, in desperate need of food, shelter, and medical supplies following the Battle of Fort Washington in November 1776. This work, painted in 1875, was created for the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition held the following year.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: History

Banished: Loyalist Women – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Oral history activity with primary and secondary resources, questions for students, transcripts, and a glossary.

Media

Colonizing America: Crash Course US History – PBS (12 min) TV-G

This PBS video teaches you about the (English) colonies in what is now the United States. It covers the first permanent English colony at Jamestown, Virginia, the various theocracies in Massachusetts, the feudal kingdom in Maryland, and even a bit about the spooky lost colony at Roanoke Island.

Prelude to Revolution: Crash Course US History – PBS (12 min) TV-G

This video teaches you about the roots of the American Revolution, leading you through the bramble of taxes, royal decrees, acts of parliament, colonial responses, and various congresses. The cost of the Seven Years War led to the British taxing colonial trade, which led to colonists demanding representation, which led to revolution.

Women and the Revolution (3 min)

Scholar Carol Berkin discusses how women played a pivotal role in the Revolution, as they were the primary consumers boycotting British taxes on cloth and tea. From The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Glossary

Alexander Hamilton: (1755 – 1804) Founding Father, first United States Secretary of the Treasury, aide-de camp to George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

Battle of Brandywine: a one-day military skirmish fought on September 11, 1777, between American and British forces. A British victory forced the retreat of George Washington and his Continental Army troops and led to the British occupation of Philadelphia.

Battle of Fort Washington: a military skirmish fought on November 16, 1776, between American and British forces in New York. A decisive British victory gave them control of Manhattan Island and forced George Washington and his American troops into New Jersey.

Battle of Lexington: along with the Battle of Concord, this was the first military engagement of the American Revolution.

Bethlehem: The largest Moravian settlement in America, established in 1741.

Boston Massacre: a riot in Boston (March 5, 1770) arising from the resentment of Boston colonists toward British troops quartered in the city, in which the troops fired on the mob and killed several persons.

boycott: to refuse to buy, use, or participate in (something) as a way of protesting : to stop using the goods or services of (a company, country, etc.) until changes are made.

Choir System: a separate living and working arrangement for Moravians based on age, gender and marital status. It was thought that this living situation would more successfully foster religious growth among individuals of like circumstances.

closed community: an often theocratic society that limits their contact with outsiders. The somewhat remote location of the Bethlehem settlement limited Moravian interaction with the majority of colonial American society.

community: a group of people with a common characteristic or interest living together within a larger society.

East India Company: (1600-1874) English trading company that pursued commercial trade of goods in the East Indies, China, India, and the land which today is part of modern Iran and Pakistan.

ecumenical: a : of, relating to, or representing the whole of a body of churches, b : promoting or tending toward worldwide Christian unity or cooperation.

emigrate: to leave one’s place of residence or country to live elsewhere.

French and Indian War: A series of military engagements between Britain and France in North America between 1754 and 1763. The French and Indian War was the American phase of the Seven Years’ War, which was then underway in Europe. In a battle between British and French forces near Quebec City in Canada, the British gained control of all of Canada.

General Economy: the system used by the Moravians where all individual labors were directed toward the betterment of the community and support of its growing itinerancy and missionary efforts. All money made and goods produced became the property of the community and not the individual. The General Economy existed from 1741 to 1762.

General Thomas Gage: (1720-1787) British military general who was appointed military governor of Massachusetts in 1774. His orders were to implement the Intolerable Acts.

Intolerable Acts: Also known as the Coercive Acts; a series of British measures passed in 1774 and designed to punish the Massachusetts colonists for the Boston Tea Party.

Jan Hus: (1369-1415) Czech/ German religious reformer who protested the doctrines of the Catholic Church. He was a key predecessor to the Protestant movement in the sixteenth-century. Followers of Hus, called “Hussites,” were the basis for the formation of the Moravian Church.

Liberty Tree: Located in Boston during the Revolutionary War, the tree came to be a rallying point for those opposed to British tyranny in the colonies and most especially for the Sons of Liberty.

Loyalist (Tory): an American upholding the cause of the British Crown against the supporters of colonial independence during the American Revolution.

Massachusetts Government Act: An act of the British Parliament that gave military governor Gen. Thomas Gage absolute authority to repeal the Massachusetts colony’s charter, effectively reducing colonial control over the government. The act gave Gage the power to appoint council members of his choosing, positions which had previously been filled by election.

Marquis de Lafayette: (1757-1834) Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, a French aristocrat and military officer who served under George Washington as a major-general in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

Moravian: a member of a Protestant denomination arising from a 15th century religious reform movement in Bohemia and Moravia.

Moravian Church: A Protestant denomination arising from a 15th century religious reform movement in Bohemia and Moravia, land that today is the Czech Republic.

missionary: a person who is sent to a foreign country to do religious work (such as to convince people to join a religion or to help people who are sick, poor, etc.)

Patriot (Whig): an American favoring independence from Great Britain during the American Revolution.

Protestant Reformation: 16th century religious movement that sought to reform the practices and beliefs of the Catholic Church.

Quaker: Also known as the Religious Society of Friends, the Quaker faith emerged as a new Christian denomination in England during a period of religious turmoil in the mid-1600’s with a strong focus on pacifism and humanitarianism.

Single Sister: the name for a single woman of marriageable age in the Moravian community. A male would be called a “Single Brother,” and so on. See Choir System.

Stamp Act of 1765: Law passed by the British Parliament on March 22, 1765; the first direct tax on the colonies, which required all American colonists to pay a tax on every piece of printed paper, which included items such as newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards.

Tea Act: (1773) an act of the British Parliament to primarily bolster the East India Company, but it had other objectives. First, the act aimed at reducing the large amount of surplus tea held by the East India Company. Second, it was intended to undercut the price of smuggled tea into the colonies. Lastly, by having the colonists purchase the tea on which the Townshend duties were paid, the colonists would be implicitly agreeing to Parliament’s right to tax them. Frustration with the Tea Act led to the Boston Tea Party.

William Penn: (1644-1718) early American Quaker and founder of the province of Pennsylvania, later the state of Pennsylvania.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 2 – Colonization and Settlement (1585-1763)

- Standard 1A – The student understands how diverse immigrants affected the formation of European colonies

- 5-12 – Analyze the religious, political, and economic motives of free immigrants from different parts of Europe who came to North America and the Caribbean.

- 5-12 – Evaluate the opportunities for European immigrants, free and indentured, in North America and the Caribbean and the difficulties they encountered.

- Standard 2B – The student understands religious diversity in the colonies and how ideas about religious freedom evolved.

- 9-12 – Describe religious groups in colonial America and the role of religion in their communities.

- 7-12 – Trace and explain the evolution of religious freedom in the English colonies

- Standard 2C – The student understands social and cultural change in British America.

- 5-12 – Explain how and why family and community life differed in various regions of colonial North America.

U.S. History Content Standards Era 3 – Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

- Standard 1A – The student understands the causes of the American Revolution

- 5-12 – Reconstruct the chronology of the critical events leading to the outbreak of armed conflict between the American colonies and England.

- Standard 1A – The student understands the causes of the American Revolution

- 9-12 – Reconstruct the arguments among patriots and loyalists about independence and draw conclusions about how the decision to declare independence was reached.

- Standard 2C – The student understands the Revolution’s effects on different social groups

- 5-12 – Compare the revolutionary goals of different groups—for example, rural farmers and urban craftsmen, northern merchants and southern planters—and how the Revolution altered social, political, and economic relations among them.

- 7-12 – Analyze the ideas put forth arguing for new women’s roles and rights and explain the customs of the 18th century that limited women’s aspirations and achievements.