During one of the darkest chapters of our nation’s history, artists grappled with how to artistically depict and interpret the conflict of the Civil War. Landscape acted as a metaphor for much of the turmoil in which our nation was engrossed. Weather phenomena were seen as apocalyptic signs that portended the future. Perhaps the phenomenon that invoked the most speculation was the aurora borealis, a dazzling display of dancing colored light. The artist Frederic Church implies the clash of Union and Confederate troops in the array of blue and red light spread across Northern skies. Similarly, Eastman Johnson’s canvas of stormy skies and gusty winds conjures up feelings of dread and uncertainty. The figure of the young girl, with her windswept hair and contemplative expression, adds a personal face to the war; a sobering reminder of the many who had been left behind and, most certainly, a reflection on the mood of the country.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

“The Girl I Left Behind Me” was the title of a ballad popular among soldiers during the Civil War. The regimental ballad came from an old Irish song, whose lyrics read:

My mind her full image retains,

Whether asleep or awaken’d,

hope to see my jewel again,

For her my heart is breaking.

Eastman Johnson, painted this work in 1872, seven years after the Civil War had ended, and during the height of Reconstruction. What can we learn about the spirit of the country in 1872 from this image? What clues does Johnson give us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Eastman Johnson painted a lone young woman, her clothes and hair are blown back by a harsh wind. Though her torso faces the viewer, she turns her head and plants her left foot towards a point beyond the picture frame as though she is determined to go forward in spite of the wind and weather. The girl wears a wedding ring that seems framed by the books she carries. Thinking of the ring, and the title of the work, who do you think may have left her behind?

Eastman Johnson painted a lone young woman, her clothes and hair are blown back by a harsh wind. Though her torso faces the viewer, she turns her head and plants her left foot towards a point beyond the picture frame as though she is determined to go forward in spite of the wind and weather. The girl wears a wedding ring that seems framed by the books she carries. Thinking of the ring, and the title of the work, who do you think may have left her behind?

Where is she going?

What do you notice about the landscape and the girl’s path? How might you forecast the weather? It’s hard to tell where the girl’s path leads. It narrows just a few steps ahead of her. Sunlight breaks through the dark clouds to frame the girl’s face and echo the outline of her windswept hair, but the sky as a whole is dark and foggy.

What’s puzzling about this picture?

Taking a look at this picture, it’s hard to know exactly what’s going on. This girl seems too young to be married, yet she wears a wedding ring. She is out for a walk with books in her hand, but the weather is less than ideal. Also, it is hard to tell where she is; only a few split-rail fences mark the landscape below her and her path narrows before it reaches the edge of the picture.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Like all artists, Eastman Johnson included meaningful details in his works. Qualities that may or may not make sense to us literally as 21st century viewers could have had symbolic meaning much clearer to 19th century audiences. Imagine that the girl in this work isn’t just a young bride, but that she represents a young country. What union might her wedding ring represent? Why might her path be unclear at this time? Why is the sky surrounding her so foggy?

Johnson’s painting shows all of the uncertainty that faced the United States in the aftermath of the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination. With no clear path and a heavy fog, Johnson’s setting is as bleak as the country’s future seemed without a strong leader for it to follow. While the title of the work refers to an ideal image of a sweetheart left at home by a soldier caught up in war, this girl may symbolize the mourning nation as it strove to move forward after the war. Though young, and in spite of what she may have lost along the way, this girl, like the nation, calmly steps ahead, resolutely facing the headwinds before her.

Historical Background

Visual Imagery in the Civil War

On December 23, 1864 – closely following two important Union victories – millions of Northerners witnessed a striking display of the aurora borealis. Many interpreted this as a sign of the North’s inevitable victory. Frederic Church’s painting by that name, though rich with associations of exploration, was probably partly inspired by that event. The colors of the northern lights in the sky certainly evoke the American flag, while the dogsled seems to be bringing hopeful news to the icebound ship. For the nineteenth-century landscape painter, the season, weather, time of day, degree of wildness or cultivation and of bareness or fertility were all symbolic. During the Civil War, painters turned to traditional symbolism of landscape imagery to comment on the war.

On December 23, 1864 – closely following two important Union victories – millions of Northerners witnessed a striking display of the aurora borealis. Many interpreted this as a sign of the North’s inevitable victory. Frederic Church’s painting by that name, though rich with associations of exploration, was probably partly inspired by that event. The colors of the northern lights in the sky certainly evoke the American flag, while the dogsled seems to be bringing hopeful news to the icebound ship. For the nineteenth-century landscape painter, the season, weather, time of day, degree of wildness or cultivation and of bareness or fertility were all symbolic. During the Civil War, painters turned to traditional symbolism of landscape imagery to comment on the war.

In this painting, Aurora Borealis, Church captures the sense of darkness before the dawn. It is a painting that can be read on several different levels. On its surface, it is about Arctic rescue. The painting depicts the S.S. United States, the ship of polar explorer Dr. Isaac Israel Hayes, wintering over in the ice in the Canadian Arctic. His sled dog team approaches the ship, as if though providing the hope of a rescue. As the ice grips the S.S. United States, and by proxy the nation, the auroras snake across the Arctic winter sky like a grim warning from God, a bleak foreshadowing of doom.

The war years had already proved to be a bounty for celestial portents. The preponderance of meteors, comets, and auroras made it seem as though the American skies, North and South, were witness to an apocalyptic battle overhead that rivaled the rolling war-dun on the ground. Chief among the phenomena invoking apocalypse and days of judgement was the aurora borealis, eerie, silent flickering of lurid light that rippled across the sky like a nocturnal, unhinged rainbow. They conjured images of nature out of control, appearing and disappearing with no warning. The aurora borealis were one of the often invoked metaphors either for imminent victory or imminent destruction – they were a malleable metaphor. Beginning in the 1850s, the appearance of the auroras spurred lengthy accounts in local newspapers that combined scientific data with astrological interpretations. At several times during the war years the aurora was uncharacteristically visible from Canada to Cuba, in 1859, 1860, and in 1864. Americans, unfamiliar with the aurora phenomenon, viewed the skies at war with themselves – interpreting them as though God himself was weighing in on the issues surrounding the Civil War.

Church’s painting can also be interpreted on a narrative level, a story about the dangers on polar exploration, the scientific fascination of a newly discovered weather phenomena, and the idea that exploration itself carries with it a fortitude that was characteristically American.

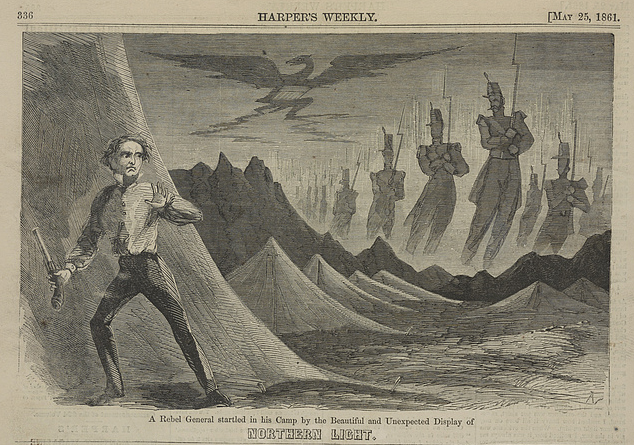

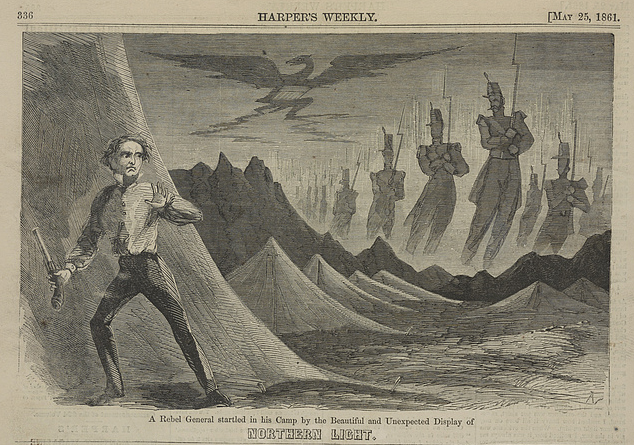

A Rebel General Startled in His Camp by the Beautiful and Unexpected Display of Northern Light, May 25, 1861, Harper’s Weekly, Library of Congress

The underlying layer of interpretation is that the subject matter of the aurora indirectly deals with the Civil War. Landscape serves as the metaphorical war. At the time Church painted this, Harper’s Weekly ran a political cartoon of a Confederate general cowering in the face of Northern light, where the auroras came around the mountain with bayonets as if they represented the oncoming Union Army. By this time in the war, there as a sense that it would never end. There was a sense that this might, in fact, be the end of the world, not simply the end of the country. Church captures the dark side of that mood and invests this painting with the kind of emotion that was prevalent in the press and in poetry at the same time. In his 1867 book on his polar explorations, titled The Open Polar Sea, Hayes mentions witnessing the aurora on January 6, 1861:

The broad dome above me is all ablaze. Ghastly fires, more fierce than those which lit the heavens from burning Troy, flash angrily athwart the sky. The stars pale before the marvelous glare, and seem to recede further and further from the earth – as when the chariot of the Sun, driven by Phaeton, and carried from its beaten track by the ungovernable steeds, rushed madly through the skies parching the world and withering the constellations . . . The colour of the light was chiefly red, but this was not constant, and every hue mingled in the fierce display. Blue and yellow streams were playing in the lurid fire; and, sometimes starting side by side from the wide expanse of the illumined arch, they melt into each other, and throw a ghostly glare of green into the face of the landscape.

Hayes’ eyewitness account seems to correspond to the colors chosen by Church (red, green, and yellow) for the aurora in the painting. In hue and weirdly undulating motion, the northern lights in Church’s painting give form to Hayes’s poetic and yet scientific descriptions. It is interesting, too, that Hayes uses the metaphor of cities burning, as this is exactly what many people thought was happening during the spectacular appearance of the aurora exactly a year earlier, on September 1, 1859.

Photography

As the war drew on, allegorical interpretations of the war, like Aurora Borealis, began to lose favor. Realism was becoming more dominant in Civil War imagery because of a greater use of and reliance on a new artistic medium – photography. The reliance on photography for visual information had much to do with a growing demand for improved accuracy of representation in visual information. While still in black and white and sepia tones, photography captured the war in a way that painting just could not.

Some 1500 photographers produced thousands of images in urban studios as well as in makeshift studios on the battlefield. Photographers like Matthew Brady carried cumbersome equipment from camp to camp, battlefield to battlefield. Yet, they kept their distance from the fighting, so almost no images exist that depict the action of battle. The most often published photographs were of bodies littering the battlefield. These images were published in newspapers around the country, searing images of the horrors of war into the minds of Americans. Though these images were certainly the most provocative, the ravage of war is more often seen in photographs of a natural landscape decimated by the firestorm of battle. Scenes of camp life, military engineering marvels like bridges and fortifications, and portraits of military officers were popular and available to the public for purchase. As a medium, photography exploded during the Civil War, widely available and easily accessible to even the poorest soldier who could afford to carry a small photographic portrait of a sweetheart back home in his pocket.

Primary Source Connections

Abraham Lincoln, notes for the “House Divided” speech, ca. December 1857, Gilder Lehrman Institute Collection.

Lincoln’s “House Divided” Speech, 1858

Read the Speech at PBS.org

This speech given at the Illinois Republican convention, kick-started Lincoln’s bid for the United States Senate. The speech was written in response to the recent Supreme Court ruling in the Dred Scott case.

A house divided against itself cannot stand.” I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become lawful in all the States, old as well as new — North as well as South.

Lincoln believed that the ruling, which held that African Americans, freed or slave, could not be American citizens, was the first step to legalized slavery in all states. Lincoln’s use of the “house divided” phrase would have been immediately recognizable, as it is attributed to Jesus in three of the Bible’s gospels.

The Gettysburg Address, 1863, Abraham Lincoln

Read the Transcript and View the Original Document at OurDocuments.gov

“Perhaps the most famous battle of the Civil War took place at Gettysburg, PA, July 1 to July 3, 1863. At the end of the battle, the Union’s Army of the Potomac had successfully repelled the second invasion of the North by the Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia. Several months later, President Lincoln went to Gettysburg to speak at the dedication of the cemetery for the Union war dead. Speaking of a “new birth of freedom,” he delivered one of the most memorable speeches in U.S. history.” – OurDocuments.gov

A Rebel General Startled in His Camp by the Beautiful and Unexpected Display of Northern Light, May 25, 1861, Harper’s Weekly

Download the image at the Library of Congress

At the time Church painted Aurora Borealis, popular magazine Harper’s Weekly ran a political cartoon of a Confederate general cowering in the face of Northern light, where the auroras came around the mountain with bayonets as if they represented the oncoming Union Army.

Title page for Hayes’s An Arctic Boat Journey, 1860.

Read the book at Archive.org

“Arctic Explorations. Lecture of Dr. J. S. Hayes before the New-York Geographical and Statistical Society,” New York Times, November 15, 1861.

Read the full speech at the New York Times.com

Dr. Isaac Israel Hayes delivered this address shortly after returning safely from his arctic explorations in October 1861:

When I left the regions of eternal ice, I little dreamed that a powerful rebellion was desolating my country, and that civil war was raging among a people which I left prosperous and happy. This great national calamity alters the relations under which we now meet. Had there been peace, I should have come before you to solicit a continuance of your countenance and influence in aiding the further prosecution of Arctic discovery, but for the present I cannot think of it. The day has come when the Republic has a right to demand the time, the money, the energies, and, if need be, the life upon the battle-field, of even the humblest of her citizens. . . . God willing, I trust yet to carry the flag of our great Republic, with not a single star erased from its glorious Union, to the extreme northern limits of the earth.

Literary Connections

“Aurora-Borealis: Commemorative of the Dissolution of Armies at the Peace,” in Battle-pieces and Aspects of War 1866, Herman Melville

“Aurora-Borealis: Commemorative of the Dissolution of Armies at the Peace,” in Battle-pieces and Aspects of War 1866, Herman Melville

Read and Download at Archive.org (Note: “Aurora” poem can be found on page 148)

The aurora also appears in poetry from the Civil War, including this work by Herman Melville. An excerpt:

What power disbands the Northern Lights

After their steely play?

The lonely watcher feels an awe

Of Nature’s sway,

As when appearing,

He marked their flashed uprearing

In the cold gloom—

Retreatings and advancings,

Artwork Connections

Cotopaxi, 1855, Frederic Edwin Church

Church has made two trips to South America, traveling through Columbia and Ecuador in 1853 and 1855. His earlier images of Cotopaxi, painted in the pre-Civil War years, had been inspired by a visions of a universe in harmony. The volcano pictured is just starting to simmer. Yet, his later images portray the volcano exploding, spewing ash miles into the air – just as the Civil War was erupting in America.

Incidents of the War: A Harvest of Death, 1863, Timothy H. O’Sullivan

“Slowly, over the misty fields of Gettysburg . . . came the sunless morn, after the retreat by Lee’s broken army. Through the shadowy vapors, it was, indeed, a “harvest of death” that was presented; hundreds and hundreds of torn Union and rebel soldiers . . . strewed the now quiet fighting ground, soaked by the rain, which for two days had drenched the country with its fitful showers. . . . Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.” This is the original caption written by photographer Alexander Gardner which accompanied this photograph by O’Sullivan in Gardner’s 1865 volume of Civil War photographs entitled, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (Volume I, Plate 36).

The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York, ca. 1862, Homer Dodge Martin

The iron-ore bed in Craig Harbor near Port Henry, New York, was one of the richest veins in the northeast. Earlier artists had pictured America’s mountain peaks and virgin forests, but by midcentury, the railroads, mines, and oil fields were the new and exciting scenes to paint. From a mineshaft that looks like a bleeding wound, tailings stream down the side of the cliff to the water, where ore was loaded onto barges. Nearby were the blast furnaces of the Bay State Iron Mine Company, which supplied the steel for America’s railroads. Railways in turn carried more raw materials to the nation’s burgeoning factories. Painted during the Civil War, Martin’s canvas quietly asserted the primacy of the North, whose strength lay in its natural resources and manufacturing.

Media

Re:Frame Episode “Auroras Are Weird” What do arctic explorers, solar burps, and the Civil War have to do with American art? Watch to find out! SAAM’s interpretive video series Re:Frame explores American art’s many meanings and connections with experts across the Smithsonian.

The Civil War and American Art: The Girl I Left Behind Me (3 min)

In this podcast, American Art Museum curator Eleanor Jones Harvey discusses six featured paintings from “The Civil War and American Art” exhibition. This episode looks at The Girl I Left Behind Me by Eastman Johnson.

The Election of 1860 & the Road to Disunion: Crash Course US History – PBS (14 min) TV-G

The tensions between the North and South were rising, due to the issue of slavery. It seemed that war was inevitable, but first the nation had to get through the election. You’ll learn how the bloodshed in Kansas, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act led directly the splitting of the Democratic party and the unlikely victory of a relatively inexperienced politician, Abraham Lincoln.

Slavery – Crash Course US History – PBS (14 min) TV-G

This video teaches you about America’s “peculiar institution,” slavery. The video discusses what life was like for a slave in the 19th century United States, and how slaves resisted oppression, to the degree that was possible. We’ll hear about cotton plantations, violent punishment of slaves, day to day slave life, and slave rebellions.

The Civil War, Part I: Crash Course US History – PBS (12 min) TV-G

In part one of a two part look at the US Civil War, this PBS video looks into the causes of the war, the motivations of the individuals who went to war, why the North won, and whether that outcome was inevitable. The North’s industrial and population advantages are examined, as are the problems of the Confederacy, including its need to build a nation at the same time it was fighting a war.

The Civil War Part 2: Crash Course US History – PBS (11 min) TV-G

This PBS video covers some of the key ways in which Lincoln influenced the outcome of the war, and how the lack of foreign intervention also helped the Union win the war. New technology and new weapons also helped to influence the outcomes of battles, and photography influenced how the public at large perceived the war.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

The Civil War and American Art – Smithsonian American Art Museum

The exhibition examines how America’s artists represented the impact of the Civil War and its aftermath. Winslow Homer, Eastman Johnson, Frederic Church, and Sanford Gifford–four of America’s finest artists of the era–anchor the exhibition.

The Civil War and American Art: Teacher Guide (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

“Approaching Research: Aurora Borealis” (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Process notes for students on how researchers investigated a question about an artwork, step-by-step.

Subject: History

The Price of Freedom: Civil War – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Americans battled over preserving their Union and ending slavery. Both sides envisioned easy victories after eleven Southern states seceded and war broke out in 1861. But the bitter, ruthless fight lasted four years, and proved to be the nation’s bloodiest and most divisive conflict. More than three million Americans saw battle: 529,332 lost their lives; another 400,000 were scarred, maimed, or disabled. This online exhibition provides historical essays paired with primary resources.

Lesson Plans

Final Farewells: Signing a Yearbook on the Eve of Civil War – Smithsonian Education

In this lesson, students examine a primary source that might seem both familiar and strange: a yearbook from 1860, complete with farewell messages from classmates. The yearbook’s owner was a Texan at Rutgers College in New Jersey, a scion of a plantation family who would go on to die for the Confederacy. On close study, the messages from his mostly northern classmates reveal much about the complexities of the “brothers’ war.”

Glossary

aurora borealis: a natural electrical phenomenon characterized by the appearance of streamers of reddish or greenish light in the sky, usually near the northern or southern magnetic pole.

Isaac Israel Hayes: (1832-1881) American Arctic explorer, physician, and politician.

Matthew Brady: (1822-1896) American photographer and photojournalist, best known for his scenes of the Civil War.

photography: the science, art, application and practice of creating images by recording light or other electromagnetic radiation, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 5 – Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

- Standard 1A –The student understands how the North and South differed and how politics and ideologies led to the Civil War.

- 5-12 – Explain the causes of the Civil War and evaluate the importance of slavery as a principal cause of the conflict.

- 7-12 – Chart the secession of the southern states and explain the process and reasons for secession.

- Standard 2A – The student understands how the resources of the Union and Confederacy affected the course of the war.

- 7-12 – Compare the human resources of the Union and the Confederacy at the beginning of the Civil War and assess the tactical advantages of each side.

- 7-12 – Analyze how the Civil War and Reconstruction changed men’s and women’s roles and status in the North, South, and West.

- 9-12 – Analyze the purpose, meaning, and significance of the Gettysburg Address.

- Standard 1A –The student understands how the North and South differed and how politics and ideologies led to the Civil War.