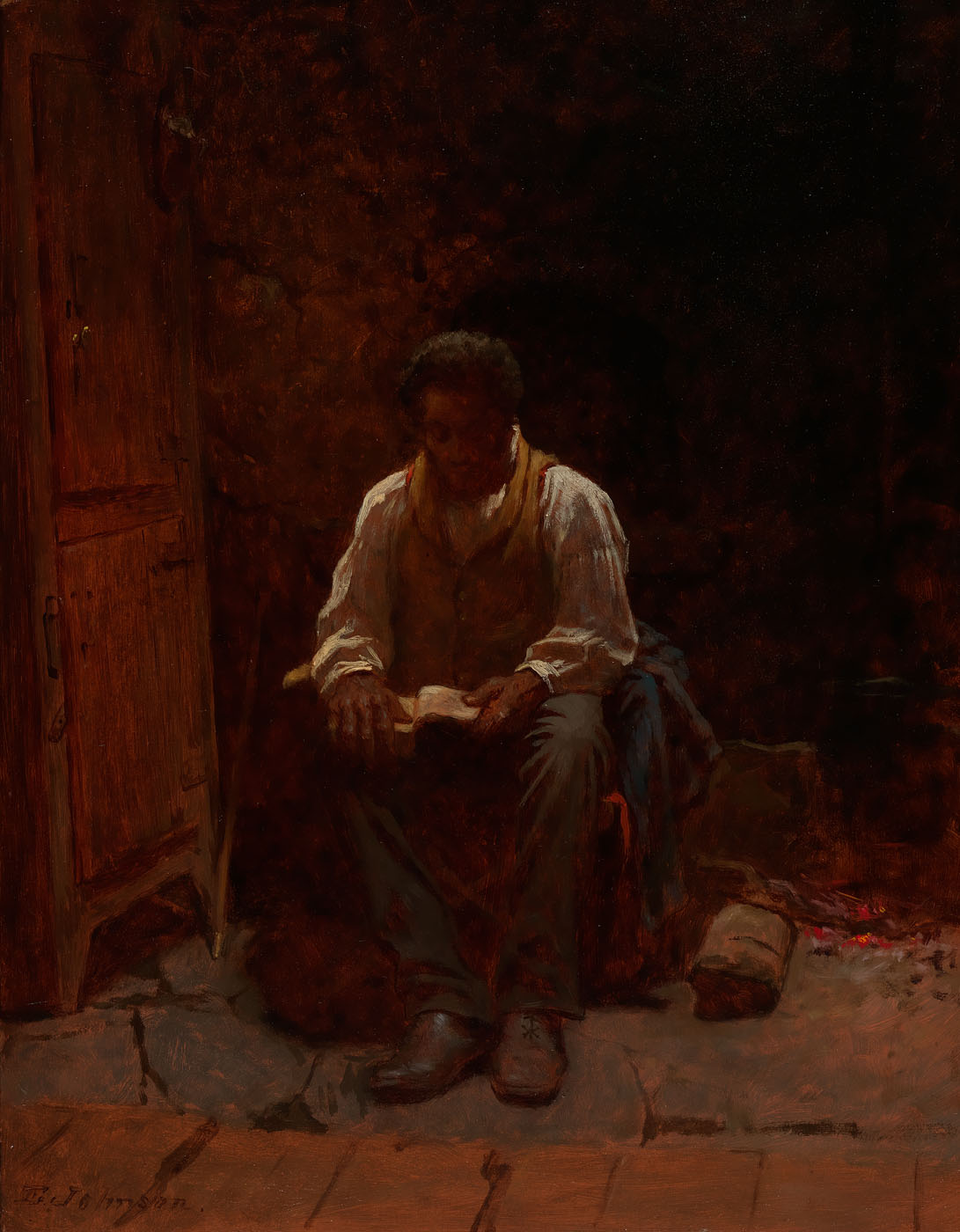

The same year as Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was read to the nation, Eastman Johnson painted The Lord is My Shepherd, an image of a black man reading the Bible. Education, more specifically the ability to read, was considered the single most important first step toward empowerment and out of slavery for black men and women. The reading of the Bible, its pages open to the passage of Exodus, provides this man with hope and promise for a better future for him and other former slaves. In the aftermath of the war, tensions lingered between newly freed blacks and their former white masters. Winslow Homer skillfully picks up on this barely suppressed tension and underlying sense of bitterness in his painting, A Visit from the Old Mistress, depicting a former mistress meeting her former slaves soon after the close of the war. Homer composed the painting from sketches he had made while traveling through Virginia with the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. It was during this time that he would have been able to visit slave quarters in order to accurately represent the small, dark cabin.The artwork conveys a silent tension between two communities seeking to understand their future. The formal equivalence between the standing figures suggests the balance that the nation hoped to find in the difficult years of Reconstruction.

Download a Teaching Poster PDF of A Visit From the Old Mistress

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Observation: What do you see?

Describe the way the artist composed the scene. How are the women presented to us?

-

- The scene takes place in the humble home of a group of African American women. Their former mistress has presumably just entered. She stands rigidly in profile, turned towards her former slaves. All of the black women, including the toddler, stare directly at their visitor with unwelcoming expressions. The standing women are of similar heights, placing them on equal footing with each other. However, the women are separated from their visitor physically. The space between the figures and their former mistress suggest that a racial divide continues. The central figure faces the viewer, her solid figure anchoring the composition. Her head turns toward the mistress; their eyes meet on an equal level.

What do the figures tell us about their life circumstances?

All of the African American figures wear earth tones that reflect the browns of the walls and the orange glow of the fireplace. In contrast, the mistress wears a formal black gown with lace trim, setting her apart as an outsider. She dangles a closed, red fan by her side. Homer originally painted a red carnation in her right hand, perhaps as a gesture of friendship. He painted over the flower, however, and it does not appear in the final composition. Why do you think he made that choice? How would the tone of the mistress’ greeting have changed if he had left the flower intact?

Two of the women in the painting have something unexpected in common. Can you identify what it is?

- The woman holding the child wears a wedding ring on her finger, as does her former mistress. Although Homer expresses the African American woman’s ring with just a tiny fleck of gold, its impact is unmistakable. In many cases, enslaved men and women were not allowed to marry, and families were often separated and sold at their master’s whim, sometimes to other states. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, former slaved rushed to reunite with their families and formalize their unions through legal marriage. Homer calls our attention to the wedding ring on the finger of the mistress, putting them on equal status as far as the rite to marriage is concerned.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Winslow Homer captures a tense encounter between a group of freed slaves and their former mistress following the Civil War. The period of Reconstruction opened a difficult new chapter in race relations in our country. Homer is able to convey the uncertainty of this complicated time in American history through a simple composition. What might be the purpose of this visit? Homer leaves us with more questions than answers.

Historical Background

Emancipation and the Civil War

Eastman Johnson painted The Lord is My Shepherd in 1863, the same year that Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into full effect. The proclamation stated that “all persons held as slaves [in the Confederate States] are, and henceforward shall be free.” The document also states that the United States government, in addition to military and naval authorities, will “recognize and maintain” their status as freed persons.

Freedom, of course, was contingent on the Union actually winning the war. The event which had preceded the proclamation and propelled Lincoln to finalize it was the strategic Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in 1862. It was this promising moment in the war that saw the Confederate forces, then in Maryland, were pushed back into Virginia. The battle, the first on Union soil, was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with 23,000 combined Union and Confederate forces dead.

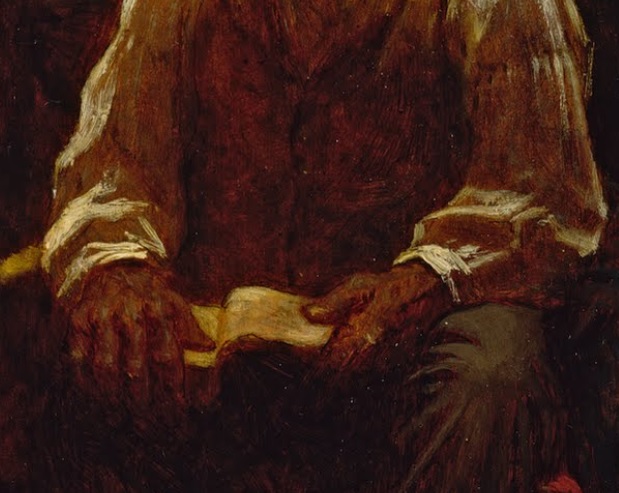

The proclamation did not expressly free all slaves from bondage (which would later be accomplished through various Reconstruction amendments), but it did provide a much needed morale boost to the Union. The proclamation also decreed the acceptance of previously enslaved blacks into the Union Army, enabling them to fight for those still enslaved and for the country which had enabled their freedom. Johnson includes a blue Union Army blanket beside the young black man as an indication of his emancipated status and his choice to fight for his country as a free citizen.

Initially, it was not Abraham Lincoln’s primary objective for the Civil War to emancipate the enslaved Southern black population; the war’s main goal was to reunite the fractured nation. Lincoln morally opposed the institution of slavery, but he knew that setting forth abolition as the war’s main objective would alienate some Northerners and bordering slave states like Maryland. Nevertheless, in July 1862 President Lincoln signed into law two acts that would help pave the way for the Emancipation Proclamation. The first, the Confiscation Act of 1862, freed all of the slaves belonging to an owner who was openly participating in rebellion against the United States. The second, the Militia Act of 1862, gave Lincoln the authority to place former slaves within the Union army in whatever roles the commander in chief saw fit, including that of Union soldier. The act had the immediate effect of not only supplying the Union army with more men, but it also siphoned off the South’s enslaved labor force which was essential to produce supplies for the war effort.

Following their victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run, Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson made the rash decision to push the weakened Union forces back into Maryland. What followed was the major Confederate loss at the Battle of Antietam, a catastrophic battle with nearly 23,000 lives lost from both sides. As a result the Confederates were forced to retreat to Virginia. Lincoln believed that the right time to introduce abolition and the human rights of the enslaved population as a primary war objective was after a Union victory when citizen and troop morale would be highest. After the Union victory at Antietam, Lincoln felt that he could now put forth his recently drafted Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet.

Once the proclamation was issued on September 22, 1862 (it did not go into effect until January 1, 1863), Lincoln was criticized by hardline abolitionists for not wording the document strongly enough to liberate all of the slaves. The specific language that Lincoln, a former lawyer, chose to use was carefully worded to define emancipation as only for those slaves residing in areas of rebellion. Had Lincoln chose language which called for complete abolition in both the North and South, he ran the risk of having border states secede from the Union and join the Confederacy.

Lincoln’s proclamation set out to achieve several objectives. One was to make abolition a main issue of the war. Another objective was to cause disruption in the Confederacy by emboldening Southern slaves to desert their masters, escape to the North and join the Union army, thereby weakening the Southern labor force. The document also more broadly sought to prevent countries like England and France from recognizing the Confederacy as a legitimate entity, and from supporting their military forces.

Literacy as Freedom

As we look upon this young black man reading a Bible, one question that comes to mind is whether or not the subject is an enslaved person. If he is a free man in the North, it would be legal for him to read at this time in 1863. But what if he is not free? Or what if he is a free black man residing in a slave state? The issue of literacy among blacks during the Civil War was a complicated one. Before the 1830s there were few restrictions on teaching slaves to read and write. After the slave revolt led by Nat Turner in 1831, all slave states except Maryland, Kentucky, and Tennessee passed laws against teaching slaves to read and write. For example, in 1831 and 1832 statues were passed in Virginia prohibiting meetings to teach free blacks to read or write and instituting a fine of $10 – $100 for teaching enslaved blacks. The Alabama Slave Code of 1833 included the following law “[S31] Any person who shall attempt to teach any free person of color, or slave, to spell, read or write, shall upon conviction thereof by indictment, be fined in a sum of not less than two hundred fifty dollars, nor more than five hundred dollars.” At this time, Harpers Weekly published an article that stated “the alphabet is an abolitionist. If you would keep a people enslaved refuse to teach them to read.” There was fear that slaves who were literate could forge travel passes and escape. These passes, signed by the slave owner, were required for enslaved people traveling from one place to another and usually included the date on which the slave was supposed to return. There was also fear that writing could be a means of communication that would make it easier to plan insurrections and mass escapes.

Sunday Morning, ca. 1877, Thomas Waterman Wood, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Slave narratives from many sources tell us how many enslaved people became educated. Some learned to read from other literate slaves, while at other times a master or mistress was willing to teach a slave in defiance of the laws. Former slave and abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass was taught the alphabet in secret at age twelve by his master’s wife, Sophia Auld. As he grew older, Douglass took charge of his own education, obtaining and reading newspapers and books in secret. He was often quoted asserting that “knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom.” Douglass was one of the few literate slaves who regularly taught others how to read. Younger slaves frequently listened outside school houses where their masters’ children were learning. Enslaved people who were caught reading or writing were severely punished, as were their teachers. In every instance these slaves and those who taught them undertook a profound risk, which for many was surmounted by the individual’s passion, commitment and imagination.

The following are two telling examples of slave narratives that discuss how slaves became literate. This first account is from James Fisher of Nashville, Tennessee, who relayed his story in 1843:

I . . . thought it wise to learn to write, in case opportunity should offer to write myself a pass. I copied every scrap of writing I could find, and thus learned to write a tolerable hand before I knew what the words were that I was copying. At last, I found an old man who, for the sake of money to buy whisky, agreed to reach me the writing alphabet, and set up copying. I spent a good deal of time trying to improve myself; secretly, of course. One day, my mistress happened to come into my room, when my materials were about; and she told her father (old Capt. Davis) that I was learning to write. He replied, that if I belonged to him, he would cut my right hand off.

Artist Eastman Johnson was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1860s, so it is plausible that he read slave narratives that demonstrated the importance of literacy and, specifically, the reading of the Bible to slaves and former slaves. One possible source Johnson might have come across was the narrative of former slave James Curry, published in the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator on January 10, 1840. Curry recalls his quest to learn to read:

My master’s oldest son was six months older than I. He went to a day school, and as I had a great desire to learn to read, I prevailed upon him to teach me. My mother procured me a spelling-book. (Before Nat Turner’s insurrection, a slave in our neighborhood might buy a spelling or hymn-book, but now he cannot). I got so I could read a little, when my master found it out, and forbad his son to teach me any more. As I had got the start, however, I kept on reading and studying, and from that time till I came away, I always had a book somewhere about me, and if I got an opportunity, I would be reading in it. Indeed, I have a book now, which I brought all the way from North Carolina. I borrowed a hymn-book, and learned the hymns by heart. My uncle had a Bible, which he lent me, and I studied the Scriptures. When my master’s family were all gone away on the Sabbath, I used to go into the house and get down the great Bible, and lie down in the piazza, and read, taking care, however, to put it back before they returned. There I learned that it was contrary to the revealed will of God, that one man should hold another as a slave. I had always heard it talked among slaves, that we ought not to be held as slaves; that our forefathers and mothers were stolen from Africa, where they were free men and free women. But in the Bible I learned that ‘God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on all the face of the earth.’

Slave Education and the Union Army

In the effort to forge a new identity after their emancipation, former slaves realized that the key to empowerment was literacy. Slaves who tended to young white children, helping to dress them and carry their books to school, watched as they grew into successful adults and witnessed firsthand the benefits of an education. The lack of reading and writing capabilities was frustrating for many as it hampered the ability to do such simple things as record a marriage or the birth of a child. With emancipation came the chance for freed blacks to acquire the education they had been denied. Eastman Johnson’s painting of a freed black man reading the Bible personifies that chance that all newly freed African Americans had to take in order to build a new life. The quest for literacy was especially important to adult blacks as once they learned how to read, they could then teach their children, producing a new generation of educated freed African Americans.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, Northern whites helped newly freed blacks to construct schools and served as teachers. In Arkansas, a visiting teacher tasked with teaching black soldiers to read and write, recalled that the soldiers “seem to feel the importance of learning and study very hard, helping themselves along very much.” Others observed that since their emancipation, “one of the most gratifying facts developed by the recent change in their condition is, that they very generally desire instruction, and many seize every opportunity in intervals of labor to obtain it.” Their determination to obtain literacy was so great that for many it ranked as high as necessities like food and shelter.

Many black soldiers also became part of a movement to educate former slaves. They advocated for the building of schools and the opportunity for others to learn. The soldiers knew that they would need to construct new lives, and education was the key to achieving that goal. Black soldier John Sweeney attested:

We have never Had an institutiong [sic] of that sort and we Stand deeply inneed [sic] of instruction the majority of us having been slaves. We Wish to have some benefit of education To make of ourselves capable of buisness [sic] In the future. . . . We wish to become a People capable of self support as we are Capable of being soldiers. . . . But Sir What we want is a general system of education In our regiment for our moral and literary elevation.” Literate black soldiers also helped to instruct illiterate soldiers to read and write when teachers were not available.

For African Americans, freedom was not something that was gained overnight; for many freedom came with the Emancipation Proclamation, for others it came when they escaped in the middle of the night and crossed into Union territory, yet for some it occurred when they donned the blue uniform of the Union Army. The army gave freedmen a purpose. Not only were they fighting for their personal right to exist, but also for the country they were indebted to. That they fought and died for the United States only solidified their claims that African Americans deserved equal rights and citizenship. Frederick Douglass argued that “Liberty won by white men would lose half its lustre.” Douglass believed that black military service and black American citizenship were inextricably linked; “Once let the black man in . . . an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

Life as a black Union soldier was not at all what many had envisioned; in fact, former slaves had some of the worst jobs in the army. They were often relegated to menial jobs, such as digging ditches or clearing away dead bodies and paid much less than their white counterparts. Though they were less likely to be killed in action, black soldiers were much more likely to succumb to diseases and bacterial infections at camp because of the tasks assigned to them. Writing to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a black soldier objected to the inequality stating, “We have come out like men and we Expected to be Treated as men but we have bin [sic] Treated more Like Dogs then [sic] men.” Additionally, if they were captured they were not seen as prisoners of war in the eyes of the Confederacy, but as property. Due to this Southern policy, the Union had no recourse for a prisoner exchange. Black soldiers were sent back to the states from which they came to either be thrown back into slavery or executed. Despite these risks, a total of 186,000 blacks served in the Union army during the Civil War which accounted for one tenth of the army’s total forces. Tellingly, half of those soldiers originated from a proslavery Southern state.

Literacy and Faith

For African Americans religion and the Christian church was, and continues to be, a unifying and enduring force within the black community. Faith and freedom were strongly intertwined. Blacks considered emancipation the beginning of their exodus out of bondage, and the Christian church became a primary focus in the lives of African Americans. During Reconstruction, the expansion and prosperity of black churches stood as a symbol of black progress to naysayers who believed the emancipated slaves could not and would not be able to organize and become productive citizens. Church congregations also provided a support system against poverty and outside discrimination and gave hope to the masses that conditions would improve for the formally-enslaved population. Church-affiliated societies and youth groups were created in order to support, instill, and enforce family values and religious ideals. Churches often provided blacks their first taste of civic independence. As self-governing institutions, their administration was tended to by their black parishioners, providing the opportunity for blacks to hold positions of leadership. Perhaps most importantly, churches served as educational institutions by encouraging literacy through the reading of the Bible.

The title of this artwork, The Lord is My Shepherd, references a phrase taken directly from the Bible in the Book of Psalms. Psalm 23 draws an analogy between a shepherd and his flock of sheep to God and his children, mankind. Eastman Johnson cleverly converts the phrase for use in a contemporary context, suggesting that God, or more likely the Union, will lead the enslaved population out of bondage. This is the likeliest meaning of the picture, but it receives the least attention.

Another theory proposes that perhaps the man is not reading from Psalms, which occurs in the middle of the Bible. Instead, he may be reading a passage from the front of the Bible where one finds the Book of Exodus with its powerful message, “let my people go.” Union soldier A.B. Randall reported in 1865 that “The Colord [sic] People here, generally consider, this war not only; their exodus, from bondage; but the road, to Responsibility; Competency; and honorable Citizenship.” That Randall chooses to use the word exodus tells us that the parallel between the plight of the enslaved black population and that of the Jews in Egypt was a common, well-known reference. Indeed, parallels can be drawn between Biblical figures and contemporary figures; Pharaoh and Southern plantation overseers, Moses and abolitionist leaders like Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman.

Relation to the Artwork

Following the cleaning and conservation of The Lord is My Shepherd, it was revealed that the blanket the man sits on is blue in color, which makes it possible that the blanket is a United States Army-issued blanket. A resulting theory proposes that this man could be “contraband,” a slave who escaped to the North and became allied with the Union army. These slaves were often taught to read by Union soldiers and they in turn taught other slaves to read. The man could also be representative of one of the first members of the United States Colored Troops, an all-black regiment of the Union army formed in 1863, which is the same year this artwork was painted. Regardless of the man’s status, to quote American Art museum curator Eleanor Jones Harvey, “the idea of determination, of initiative . . . the idea of taking your future into your own hands becomes a central part of Eastman Johnson’s narrative of the American Civil War.”

Racial Relations during Reconstruction

The Reconstruction Era attempted to reintegrate the Confederate states into the Union, on the grounds that full civil and political equality for African Americans be instituted in those Southern states. By juxtaposing the two races, artist Winslow Homer raised questions central to the reconstruction period of American history: what would the relationship be between former slaves and former masters now that they were all free citizens of the United States? What rights would the emancipated have? Homer’s painting not only alludes to these broad questions, but it addresses the specific topic of the civil rights of emancipated families.

The era of Reconstruction got off to a positive start from the end of the war to 1870. Those five years saw the ratification of three constitutional amendments; the Thirteenth Amendment had abolished slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment addressed citizenship rights and equal protection under the law and finally, the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited discrimination in voting rights based on color, race or previous condition of servitude, thereby expanding the range of American democracy to many more citizens. But these amendments did nothing to alleviate tensions or to resolve conflicts between freed slaves and their former slaveholders. The end of the war unraveled the power slaveholders held over their freed slaves. The mistress in Homer’s 1876 painting A Visit from the Old Mistress may be experiencing one of the most common postwar adjustments: confronting her formerly enslaved black women with whom she must now negotiate for their wage labor. The artist echoes the moment of disconnect described by one former slaveholding woman who wrote, “It seemed humiliating to be compelled to bargain and haggle with our own former servants about wages.” That irritation makes profoundly clear how deeply some of these white women misunderstood and underestimated the effects of slavery and how little they had comprehended the minds of those who had been enslaved.

A Visit from the Old Mistress projects the dismay felt by an overwhelming majority of former slaveholders who discovered that their slaves did not in fact love them or wish to be enslaved, no matter how benign the owner might have been. One woman wrote to her sister that her former slaves had left “to assume freedom without bidding any of us an affectionate adieu.” They wrote with apparently genuine shock and a sense of betrayal when inevitably their newly freed slaves left for the promise of emancipation or remained to assert their freedom where they already lived. The animosity evident between this white woman and her former slaves in A Visit from the Old Mistress shows that Homer understands this disconnect and has found a powerful way to make it visible. The mistress has returned, expecting to be greeted by the formerly enslaved people who loved her, only to find herself mistaken. They are not happy to see her, and the painting seethes with hostility, anger, and bitterness. Homer’s composition highlights an issue that had not yet been resolved: the understanding that both black and white carried baggage from slavery and the war years.

Under slavery African American families had been at the mercy of their mistress or master who could at any time part husband from wife or parent from child. Homer depicts a mother holding on tightly to her child, who can no longer be sold away from her family by this mistress or by any other. He also shows both the visiting old mistress and the mother holding the child wearing gold wedding rings, which are often difficult to see in reproductions, but clear to the naked eye. While Homer was often careless about precise visual details and was attacked by contemporary critics for his “lack of finish,” he carefully delineated each of these wedding bands with its own highlight and shadow.

Sunday Morning in Virginia, 1877, Winslow Homer, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Art Museum

Homer often paired this painting in exhibitions with his 1877 artwork, Sunday Morning in Virginia, setting up parallels between the two paintings in size, composition, and theme. Sunday Morning in Virginia depicts three African American children listening intently to a young African American girl who points to an open Bible on her lap, instructing the children how to read. Nearby an elderly African American woman, presumably a former slave, sits by the group. She appears deep in thought, her gaze indicating her attention is elsewhere. Homer sets up a dichotomy between the two generations, one who certainly has clear memories of the restrictions slavery imposed, and another that has, for the most part, grown up in the freedom of the Reconstruction era. The artist addresses major changes in the lives of freed people after emancipation which dealt with how much control blacks had over their own lives in post-emancipation America. Specifically, it was illegal for slaves and free blacks to gather for the purpose of learning to read or write. Imprisonment, whippings, and fines were several punishments for disobeying the law.

The confrontation depicted in A Visit from the Old Mistress can be assumed, from the title as well as the physical setting in a rough cabin, to be set on or near a Southern plantation after the Civil War. Homer is implying that, as was often the case, these former slaves continued to live around the plantation where they had once lived. Homer does not tell an elaborate story with many gestures or strong expressions – he places these people together in a relatively neutral way so that the viewer may fill in much of the emotional detail from his or her own knowledge and beliefs. Homer, as a Northerner, would have seen such a story primarily from the outside, but viewers with different backgrounds might bring far more to the story. The juxtaposition of freed women with their former mistress in the composition suggests the sweeping changes that occurred in racial relations on plantations after emancipation.

Before emancipation, the mistress managed her home and was in charge of slaves that serviced the main house. All enslaved women on a plantation would have spent some time in the main house, but the amount of time spent there varied depending on their roles and ages. Those who were closest to the mistress were the house slaves, relegated to domestic roles such as cooks, chambermaids, nurses, and washerwomen. Their duties included dressing the white women and children, taking care of laundry, cooking meals, looking after white children and general household cleaning. Further from the center of the main household were the “domestic producers.” These female slaves helped to produce and gather items such as milk, butter, eggs, vegetables and fruits, preserves, thread and textiles.

The enslaved women who were the farthest outside the realm of the white mistress were the female field slaves who worked alongside enslaved men to plant, hoe and harvest crops. Field labor was usually divided between tasks done by women, such as sowing or hoeing, and those allotted to men, like plowing and ditching. These physically demanding tasks were performed all day, from before sunrise to after sunset. When field slaves became ill, injured or at the end of a pregnancy they worked indoors, spinning or carding cotton until they were able to return to the fields. Slaves with many young children might also be spared from field labor, though they were still expected to work many long hours. Inclement weather also brought the field slaves inside the main house to work other jobs.

Slaves had little certainty in their lives, and many unexpected changes were made at the direction of the white mistress. She might decide to transfer a field slave to domestic production, or introduce a domestic producer to household tasks. The mistress could also choose to punish a slave by assigning her unfamiliar tasks in a new environment, such as moving a house slave to the heavy work of the fields or moving a relatively independent field slave into the close scrutiny of housework.

Whether the adult black women shown in Homer’s A Visit from the Old Mistress were formerly house slaves, domestic producers, or field slaves, they would have had a personal history of the way the mistress managed her household and her slaves. The level of tension between these women would depend a great deal on how the mistress treated her slaves and what had happened to the people of this particular plantation before and after the Civil War. The young child, however, was likely born after emancipation and her relationship with the mistress would likely start on a different foundation than that of her older relatives.

Life after Emancipation

The Freedman’s Bureau was created in 1865 to look after the rights of newly freed slaves, providing them with social, education and economic services. The bureau, along with churches and missionary societies, helped to set up more than three thousand schools in the South attended by freed blacks. Education remained critically important to freed blacks in their quest for civic equality, but land ownership offered them the opportunity for economic freedom. Many of these former slaves believed that they had a moral right to the land that they had previously toiled while they were enslaved. After much debate, in 1865 Congress authorized the Freedman’s Bureau to rent 40 acre parcels of abandoned or confiscated farmland to freed blacks, with the eventual option to buy. This redistribution of farmland is a concept referred to as forty acres and a mule. In 1866 the Southern Homestead Act was passed by Congress, giving preference to blacks for access to public land in five southern states. However, a short time later President Andrew Johnson nullified the previous acts and ordered that all of the redistributed land be returned to the original owners. With the cost of land available through the Homestead Act of 1862 too high for most blacks and with the institution of Black Codes, owning land and economic independence for freed blacks became near impossible.

Legal marriage was also a high priority for former slaves. The Freedman’s Bureau was deluged with requests by freed blacks to be legally married. Previously under the laws of Southern slave states, slaves were considered property and therefore could not create or enter into contracts. While many slaves took part in symbolic marriage ceremonies, these marriages had no validity in the eyes of the law. The rights of the master over the slave were paramount. Slave families could be torn apart whenever their master decided, for his own purposes. Parents had no right to their children as they too were considered property of the slave owner. In Louisiana, the law stated that slave children could not be sold away from their mothers until they reached the age of ten, but since slaves could not testify against white people in court, such laws had little force. A corporal in the U. S. Colored Troops explained to his troops the importance of Virginia’s 1866 act legitimizing slave marriages, “The Marriage Covenant is at the foundation of all our rights. In slavery we could not have legalized marriage, now we have it . . . . and we shall be established as a people.”

Whites, too, saw legal black marriage as a high priority for both administrative and moral reasons. Among other things, it was important to create laws that would allow children conceived during slavery to be legitimate. If all children born under slavery have been considered illegitimate, they would all have become an expensive population of wards of the state. With a legal marriage in place, symbolized by the ring on the black woman’s hand, the child in A Visit from the Old Mistress is legitimate and will bear her father’s family name. Though the husband/ father figure is not present in the composition, the black mother’s wedding ring is a subtle yet powerful reminder of his presence.

In the months after emancipation freed former slaves, now able to travel, moved around the South in search of the family members from whom they had been torn during slavery times. When men and wives found each other, they would often go the Freedman’s Bureau to have their unions made legal. A Union officer wrote to his wife in May 1865, “Men are taking their wives and children, families which had been for a long time broken up are united and oh! such happiness. I am glad to be here.” An army chaplain attached to a regiment of black soldiers in Arkansas, reported that he spent much of his time conducting such ceremonies: “Weddings, just now, are very popular, and abundant among the Colored People. They have just learned, of the Special Order No’ 15. of Gen Thomas by which, they may not only be lawfully married, but have their Marriage Certificates, Recorded, in a book furnished by the Government. This is most desirable; and the order, was very opportune.”

The Black Codes instituted by these states severely restricted the rights of newly freed blacks. With these codes in place, black people were still not full citizens. Due to President Andrew Johnson’s lackadaisical Reconstruction policy and his support of former Confederate political leaders, the Southern states attempted to reinstate slavery in all but name. The codes allowed officials to arrest blacks who could not document residence or employment. Those arrested were sentenced to forced labor on road construction crews or farms. One of the Black Code laws that might have affected the child depicted in A Visit From the Old Mistress was the Apprenticeship Law which allowed judges to take black children from their parents if it was deemed that they could not properly support their children. These children were often then apprenticed to former slaveholders. Former masters had the strongest right to seize children of their former slaves. These laws were quickly questioned in court and were largely removed under Reconstruction, but long and expensive court fights were necessary for African American parents to regain the custody of their children.

Soon after the Civil War share cropping emerged as the dominant mode of labor in the South, as the Freedman’s Bureau had encouraged emancipated people to return to work on plantations. This was due to the larger concern of reviving the Southern economy after the war. While a reformed labor system was important, getting crops growing in the fields again became the higher priority. Consequently, former slaves were encouraged to return to work (under contract) for their former masters. Initially these labor contracts between freed blacks and white plantation owners were supervised by the Freedman’s Bureau, but slowly this supervision began to wane. White landowners were soon able to take advantage of this lack of supervision, coercing more favorable contracts for themselves. Even after the repeal of the Black Codes, former slaveholders could have held a black family in such an oppressive share cropping agreement that they were unable to send their children to school and had to keep them working on the plantation to save the family from sliding into poverty.

Primary Source Connections

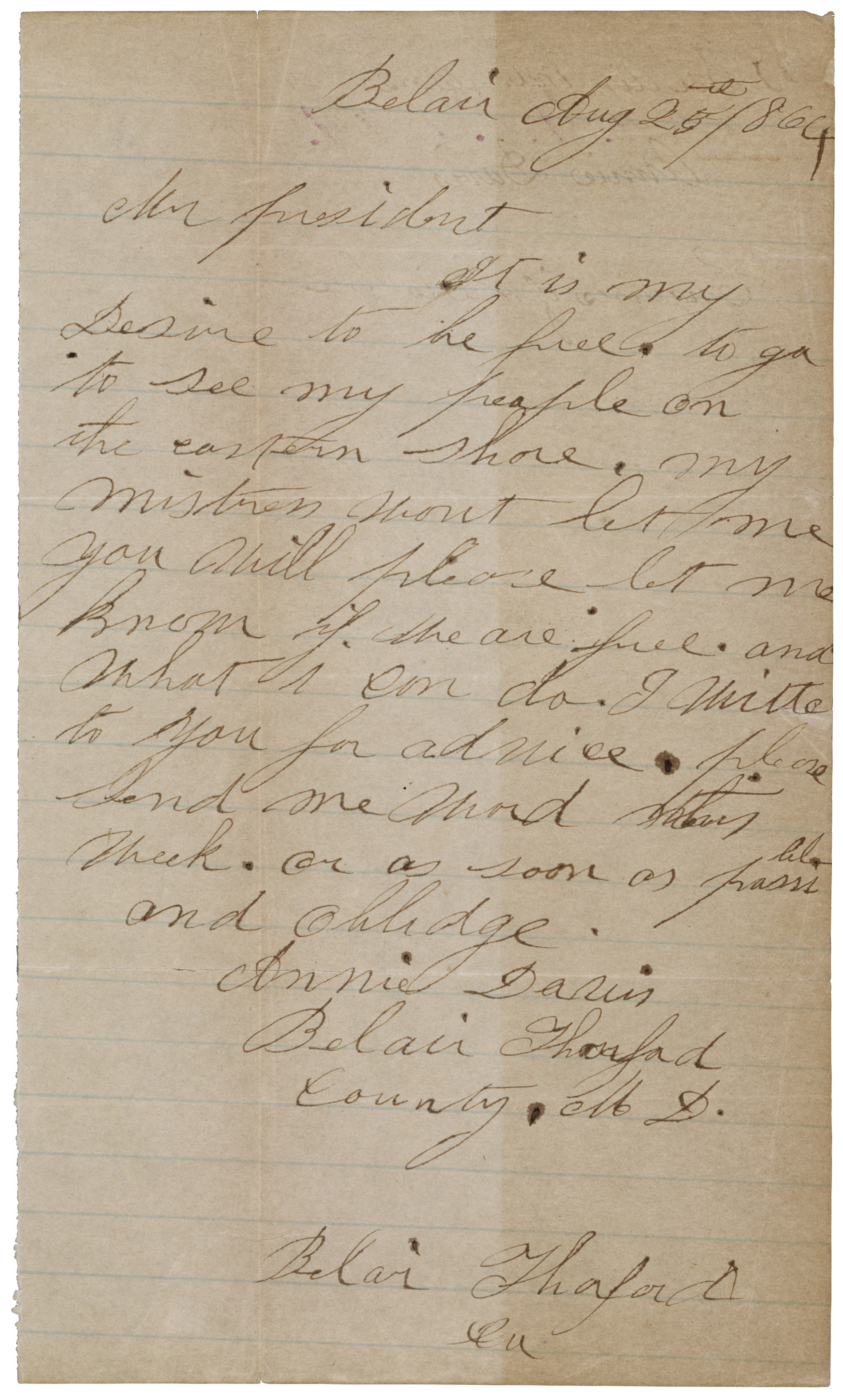

Letter to President Abraham Lincoln from Annie Davis, 1864 – National Archives

Learn more at DocsTeach.org

The Emancipation Proclamation did not free all enslaved people in the United States in 1863 – it only applied to those states that were on rebellion against the U.S. Border states, like Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, were therefore exempt from the proclamation. It was not until the 13th Amendment was ratified on December 6, 1865 that the entire enslaved population became free. Annie Davis’ letter to President Lincoln is reflective of the confusion African Americans endured at this time. Writing from Belair, Maryland, Annie writes, “Mr. President, It is my Desire to be free. Will you please let me know if we are free.”

Connect it with the Artwork: “Teaching with Documents: Annie Davis’ Letter to President Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress“

The War-Time Journal of a Georgia Girl, 1864–1865, 1908, Eliza Frances Andrews

The War-Time Journal of a Georgia Girl, 1864–1865, 1908, Eliza Frances Andrews

Read it at Documenting the American South

Emancipation did not solve all of the problems faced by African Americans. Many continued to work the fields as sharecroppers or to perform household labor—similar work they had done during slavery. Those that stayed in the South navigated the shifting relationship between the races that would influence Southern history for years to come. The diary of Eliza Frances Andrews describes these changes from the point of view of a former slaveowner:

“Arch has “taken freedom” and left us, so we have no man-servant in the dining room. . . . I feel sorry for the poor negroes. They are not to blame for taking freedom when it is brought to their very doors and almost forced upon them. Anybody would do the same, still when they go I can’t help feeling as if they are deserting us for the enemy, and it seems humiliating to be compelled to bargain and haggle with our own servants about wages.”

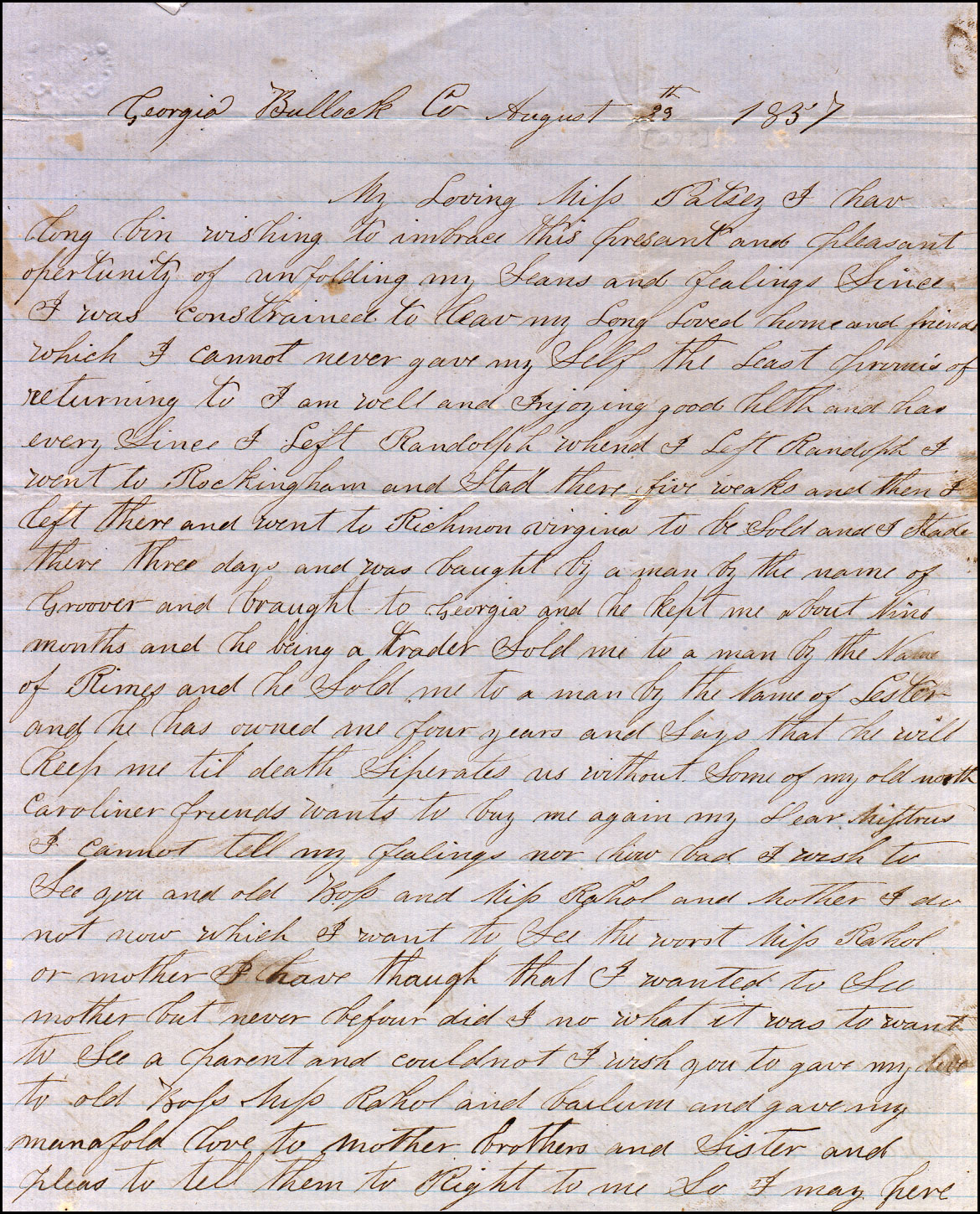

Vilet Lester letter to Miss Patsey Patterson, August 29, 1857

Vilet Lester letter to Miss Patsey Patterson, August 29, 1857

Read the transcripted letter and see the document at the Special Collections Library at Duke University

Vilet was once owned by the Patterson family who lived in Randolph County, North Carolina. Vilet signed this letter “your long loved and well wishing play mate as a servant until death” which might indicate that Vilet and Patsey Patterson were raised together as children. In this excerpt, Vilet expresses to Patsey how much she misses her former mistress and her family. “I hav long bin wishing to imbrace this presant and pleasant opertunity of unfolding my Seans and fealings Since I was constrained to leav my Long Loved home and friends which I cannot never gave my Self the Least promis of returning to. . . . my Dear Mistress I cannot tell my fealings nor how bad I wish to See you and old Boss and Mss Rahol and Mother.”

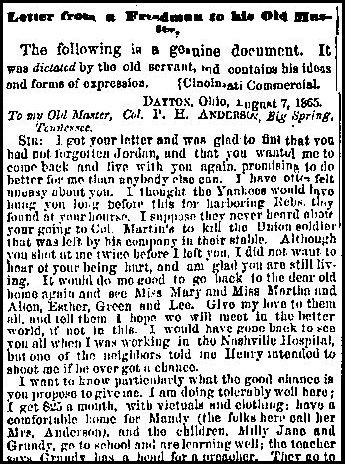

Jourdan Anderson letter to his former master, Colonel P.H. Anderson, August 7, 1865

Jourdan Anderson letter to his former master, Colonel P.H. Anderson, August 7, 1865

Read the entire letter at “History Matters” – George Washington University

In August 1865, Colonel Anderson wrote to his former slave Jourdan, requesting that he come back to work on his farm. Since his emancipation, Jourdan and his family had moved to to Ohio where Jourdan had found found paid work, his kids were happy attending school, and he and his wife were unequivocally accepted as members of the community. An excerpt from Jourdan’s deadpan, satirical response to his former master is below:

“Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. . . . I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. . . . As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you.”

“Education in the Southern States.” Harper’s Weekly, November 9, 1867

“Education in the Southern States.” Harper’s Weekly, November 9, 1867

Download the article (PDF)

The article, written in 1867, makes a passionate case for the education of Southern blacks: “For if it were essential that the freedmen should be enfranchised, which is indisputable, it is not less necessary that they should be educated. . . . To abandon them to the class which lately held them enslaved . . . is not only to leave them without any safeguards of civil rights, but it is to condemn them to hopeless ignorance.”

Letter from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper about the Emancipation Proclamation, 1862

Letter from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper about the Emancipation Proclamation, 1862

Read it at Archive.org (Letter on page 766)

Excerpt: “Yes, we may thank God that in the hour when the nation’s life was convulsed, and fearful gloom had shed its shadows over the land, the President reached out his hand through the darkness to break the chains on which the rust of centuries had gathered. Well, did you ever expect to see this day? I know that all is not accomplished; but we may rejoice in what has been already wrought, — the wondrous change in so short a time. Just a little while since the American flag to the flying bondman was an ensign of bondage; now it has become a symbol of protection and freedom. Once the slave was a despised and trampled on pariah; now he has become a useful ally to the American government. From the crimson sods of war springs the white flower of freedom, and songs of deliverance mingle with the crash and roar of war. The shadow of the American army becomes a covert for the slave, and beneath the American Eagle he grasps the key of knowledge and is lifted to a higher destiny.”

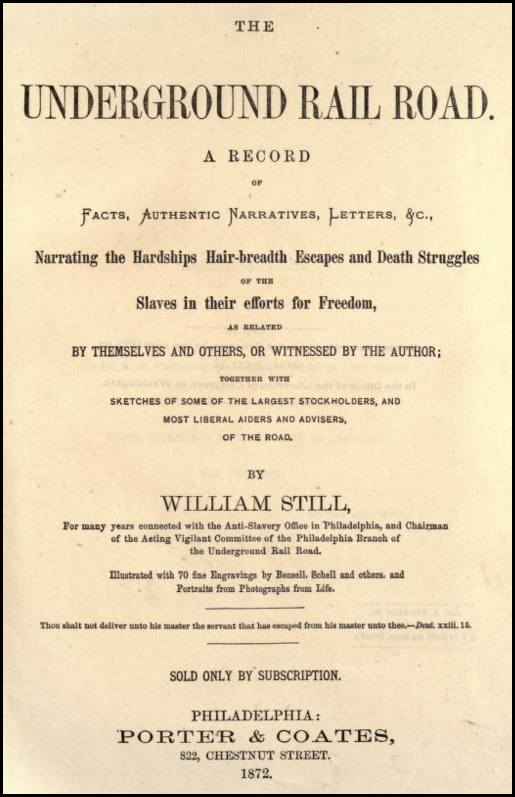

Source: The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c . . ., 1872, William Still

Letter from Harriet Beecher Stowe, November, 1862

Letter from Harriet Beecher Stowe, November, 1862

Read it at Archive.org (Letter on page 266)

Excerpt: “This very day the writer of this has been present at a solemn religious festival in the national capital, given at the home of a portion of those fugitive slaves who have fled to our lines for protection, — who, under the shadow of our flag, find sympathy and succor. The national day of thanksgiving was there kept by over a thousand redeemed slaves, and for whom Christian charity had spread an ample repast. Our sisters, we wish you could have witnessed the scene. We wish you could have heard the prayer of a blind old negro, called among his fellows John the Baptist, when in touching broken English he poured forth his thanksgivings. We wish you could have heard the sound of that strange rhythmical chant which is now forbidden to be sung on Southern plantations, — the psalm of this modern exodus, — which combines the barbaric fire of the Marseillaise with the religious fervor of the old Hebrew prophet: – “Oh, go down, Moses, Way down into Egypt’s land! Tell King Pharaoh, To let my people go! Stand away dere, Stand away dere, And let my people go!””

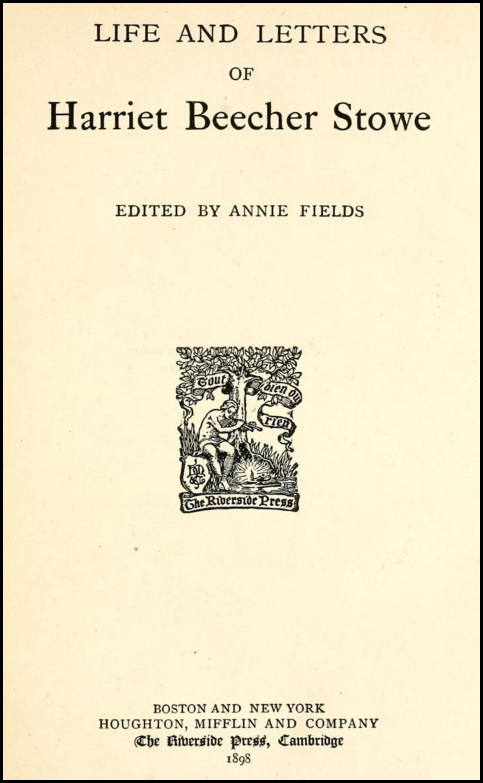

Source: Life and Letters of Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1897, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Annie Fields

Literary Connections

Fiction:

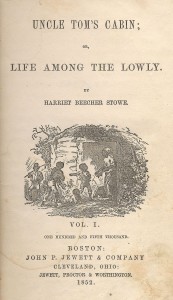

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe

Read it at Archive.org

Stowe’s most well-known novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin forever changed that was that Americans viewed slavery. Published in 1852 well before the start of the Civil War, Stowe was furious over the Compromise of 1850, which attempted to seek a compromise between free and slave states but in actuality eliminated what little freedoms runaway slaves had and required ordinary citizens (no matter their stance on slavery) legally required to turn in fugitives. Resolute, Stowe channeled her frustrations into the novel and said, “I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” The novel is credited with galvanizing the abolitionist movement

Nightjohn, 1995, Gary Paulsen – Grades 7 and Up

Nightjohn, 1995, Gary Paulsen – Grades 7 and Up

Find it in a Library

“Sarny, a female slave at the Waller plantation, first sees Nightjohn when he is brought there with a rope around his neck, his body covered in scars. He had escaped north to freedom, but he came back to teach reading. Knowing that the penalty for reading is dismemberment, Nightjohn still returned to slavery to teach others how to read. And twelve-year-old Sarny is willing to take the risk to learn. Set in the 1850s, Gary Paulsen’s groundbreaking new novel is unlike anything else the award-winning author has written. It is a meticulously researched, historically accurate, and artistically crafted portrayal of a grim time in our nation’s past, brought to light through the personal history of two unforgettable characters.” – Scholastic

The Invention of Wings, 2014, Sue Monk Kidd – Grades 7-12

The Invention of Wings, 2014, Sue Monk Kidd – Grades 7-12

Find it in a Library

The Invention of Wings details the story of Sarah, a young white girl living in nineteenth century Charleston, South Carolina, who receives the gift of a slave girl, Handful, for her eleventh birthday. The book follows the complicated relationship that develops between mistress and slave over the course of thirty years. Despite obvious differences, their storylines parallel one another, for each woman endures constraints placed on her due to her position in society. Sarah and Handful form a complex relationship marked by guilt, defiance, estrangement, love, and friendship. The book is based off of the real life story of Sarah Grimke, an American abolitionist and activist of the women’s suffrage movement.

Non-Fiction:

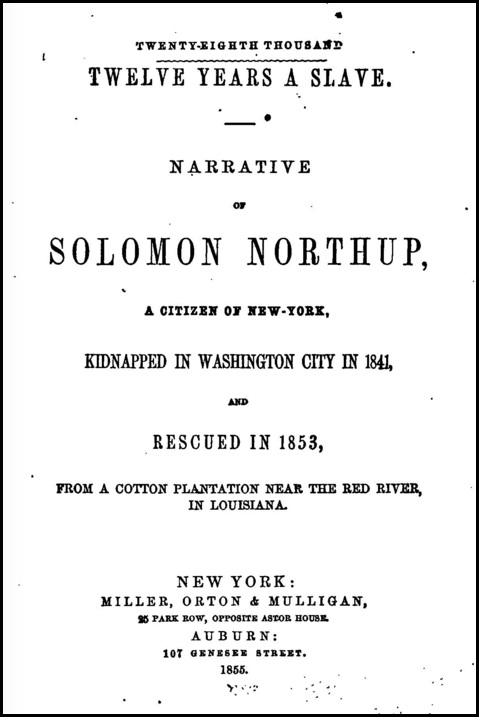

Twelve Years a Slave, 1853, Solomon Northup

Twelve Years a Slave, 1853, Solomon Northup

Read it or Download at Project Gutenberg

Published eight years before the Civil War, this memoir tells the story of Solomon Northup a black man born free, who was kidnapped and sold into slavery. The memoir was made into a major motion picture of the same name in 2013.

Artwork Connections

Sunday Morning , ca. 1877, Thomas Waterman Wood

, ca. 1877, Thomas Waterman Wood

Painted around 1877, after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, this painting depicts an elderly woman and child reading a book together. The book is important in this context because enslaved people were not allowed to read. Literacy for freedmen and women, and the opportunities it could provide, were important results of abolition.

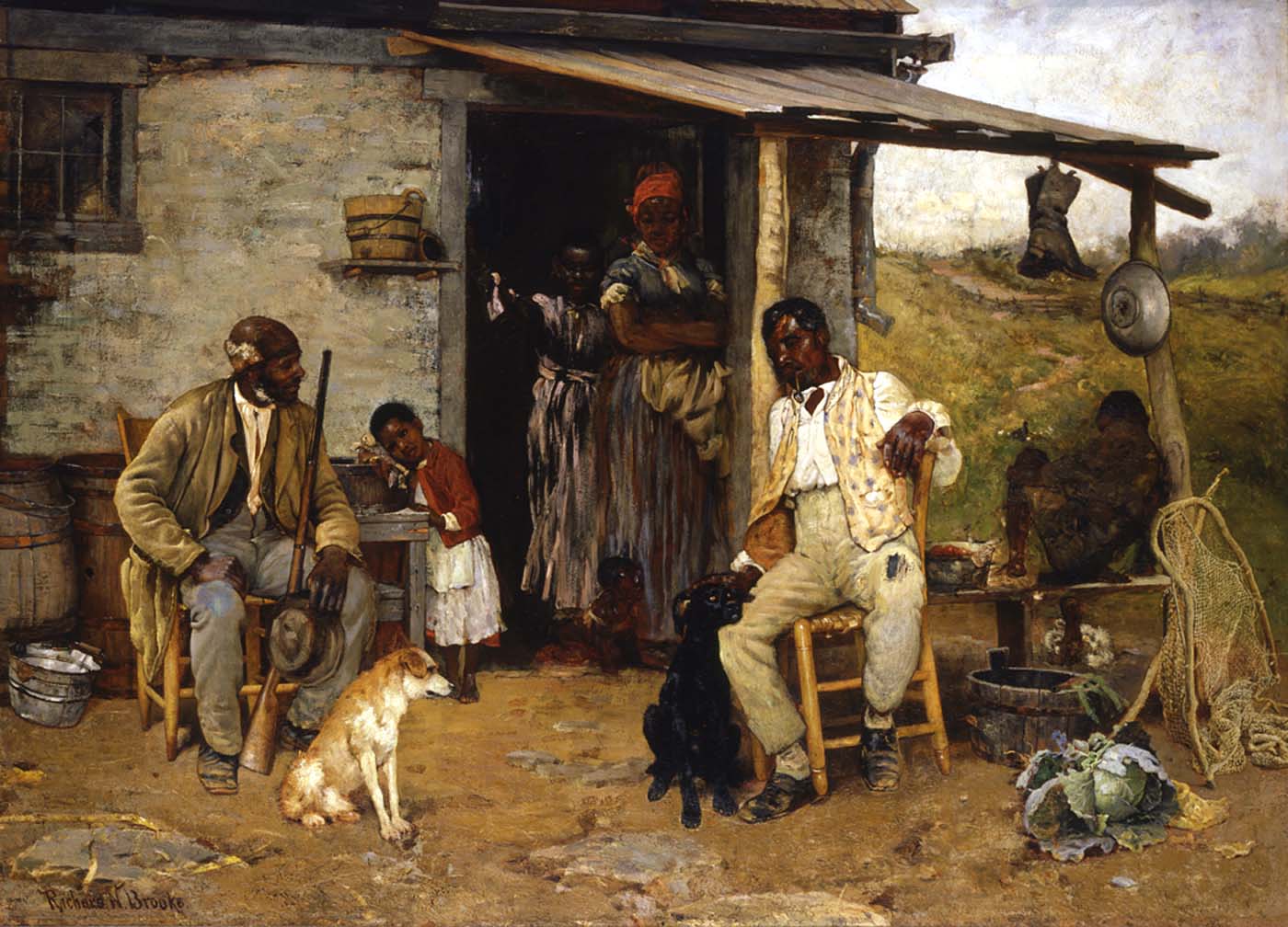

A Dog Swap, 1881, Richard Norris Brooke

Richard Norris Brook is best-known for his representations of African American family life in Northern Virginia. His scenes of everyday life possess a degree of dignity and humanity that was seldom seen in nineteenth-century depictions of blacks. Of his portrayal of African Americans, Brooke wrote, “The free range of subject afforded by Negro domestic life has been strangely abandoned to works of flimsy treatment and vulgar exaggeration. That peculiar humor which is characteristic of the race, and varies with the individual, cannot be thus crudely conveyed . . . It has been my aim, while recognizing in proper measure the humorous features of my subject, to elevate it to that plane of sober and truthful treatment.”

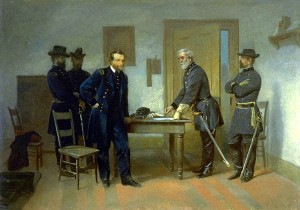

Lee Surrendering to Grant at Appomattox, ca. 1870, Alonzo Chappel

On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee officially surrendered to Union Army General Ulysses S. Grant in the McLean House in the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia, ending the nation’s deadliest conflict.

Media

The Civil War and American Art: The Lord is My Shepherd (3 min)

In this podcast, American Art Museum curator Eleanor Jones Harvey discusses six featured paintings from “The Civil War and American Art” exhibition. This episode looks at The Lord Is My Shepherd by Eastman Johnson.

The Civil War and American Art: A Visit from the Old Mistress (3 min)

In this podcast, American Art Museum curator Eleanor Jones Harvey discusses six featured paintings from “The Civil War and American Art” exhibition. This episode looks at A Visit from the Old Mistress by Winslow Homer.

Reconstruction and 1876: Crash Course US History – PBS (13 min) TV-G

This video discusses the gains made by African-Americans in the years after the Civil War, and how they lost those gains almost immediately when Reconstruction stopped. You’ll learn about the Freedman’s Bureau, the 14th and 15th amendments, and the disastrous election of 1876. Also explored are the goals of Reconstruction, its successes, and ultimate failure.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

“Teaching with Documents: Annie Davis’ Letter to President Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress“ – Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Archives.

A study of the featured document and painting will give students a greater understanding of the multi-step process of emancipation and the changing relationship that developed between freed slaves and former slave owners.

The Civil War and American Art – Smithsonian American Art Museum

The exhibition examines how America’s artists represented the impact of the Civil War and its aftermath. Winslow Homer, Eastman Johnson, Frederic Church, and Sanford Gifford – four of America’s finest artists of the era–anchor the exhibition.

The Civil War and American Art: Teacher’s Guide (PDF) – Smithsonian American Art Museum

What can American Art teach us about the transformative impact of the Civil War on the country?

A House Divided: Reconstruction – Smithsonian American Art Museum

How might history have been different if alternate plans for the Reconstruction of the South had been put into practice?

A House Divided: Civil War Photography – Smithsonian American Art Museum

What can photographs of the Civil War tell us about the conflict and developments in the documentation of war?

Oh Freedom! – Smithsonian American Art Museum

Teaching African American Civil Rights Through American Art at the Smithsonian

Subject: History

The Civil War and American Art: The Alphabet is an Abolitionist – Smithsonian American Art Museum

This blog post is part of a monthly Eye Level feature on the exhibition The Civil War and American Art. Curator Eleanor Harvey talks about many of the important intersections between American art and the Civil War.

The Price of Freedom: Reconstruction – Smithsonian National Museum of American History

This online exhibition provides historical essays paired with primary resources.

The New York Times’ 1853 Coverage of Solomon Northup, the Hero of “12 Years A Slave” – Smithsonian Magazine, March 3, 2014.

Subject: Music

Singing for Justice: Following the Musical Journey of “This Little Light of Mine” – Smithsonian Folkways

Students will learn the history behind “This Little Light of Mine,” following the song through slavery, the civil rights movement, and up to its current day applications. Students will also learn to sing the song itself in multiple languages and will be prompted to write about their learning experiences after each session.

Lesson Plans

Final Farewells: Signing a Yearbook on the Eve of Civil War – Smithsonian Education

In this lesson, students examine a primary source that might seem both familiar and strange: a yearbook from 1860, complete with farewell messages from classmates. The yearbook’s owner was a Texan at Rutgers College in New Jersey, a scion of a plantation family who would go on to die for the Confederacy. On close study, the messages from his mostly northern classmates reveal much about the complexities of the “brothers’ war.”

Glossary

Alabama Slave Code of 1833: slave codes (like the 1833 Alabama code) were sets of laws that restricted aspects of slaves’ lives to various degrees depending on the state. These codes controlled slave travel, marriage, education, and employment. They also set rights for slave owners.

Battle of Antietam: September 17, 1862; the first major battle of the Civil War to be fought on Union territory and the deadliest single day of fighting in American history.

Black Codes: laws instituted by individual states that restricted the rights of emancipated blacks.

Book of Exodus: the second book of the Old Testament of the Bible, Exodus describes the plight of the Israelites and their subsequent flight out of Egypt, led by Moses. This story drew comparisons to the plight of African American slaves in the nineteenth century.

Book of Psalms: a compilation of songs, poems, lyrics, and prayers. The subject matter centers on episodes of Israel’s history.

Confiscation Act of 1862: The second of two laws which were passed by Congress in an attempt to free the slaves in the Confederate South.

Fifteenth Amendment: (passed 1869; ratified 1870) guaranteed all American male citizens, regardless of race, the right to vote.

Fourteenth Amendment: (passed 1866; ratified 1868) prohibited states from violating the rights of its citizens, providing equal protection under the law.

forty acres and a mule: a concept of land redistribution for freed slaves, whereby Congress authorized the Freedman’s Bureau to oversee the rental of 40 acre parcels of abandoned or confiscated farmland, (formerly owned by Southern plantation owners) with the eventual option to purchase.

Frederick Douglass: (1818-1895) a former slave himself, Douglass was an African American social reformer, abolitionist, writer, and statesman.

Freedmen’s Bureau: A United States Government agency that aided free blacks during the Reconstruction Era.

Harriet Tubman: (1822-1913) a former slave, she was an African American abolitionist and social reformer. Best known for her association with the Underground Railroad, through which she helped nearly seventy friends and family escape slavery.

Homestead Act of 1862: signed by President Lincoln, the act encouraged westward migration by providing settlers with 160 acres of public land. After five years of continuous residence, settlers were given the option to purchase the land.

Militia Act of 1862: Enabled African Americans to participate in the war effort as soldiers and laborers. This was an important precursor to the creation of the United States Colored Troops.

Plessy v. Ferguson: (1896) The outcome of this Supreme Court case established the precedent that separate facilities for blacks and whites was constitutional, as long as they were “equal.”

Robert E. Lee: (1807-1870) Commanding general of the Confederate States Army.

Second Battle of Bull Run: August 28-30, 1862; a Confederate victory led by General Stonewall Jackson. The battle precipitated the Confederate invasion into Union territory, when they crossed the Potomac River into western Maryland just days later on September 5, 1862.

share cropping: a system in which freed blacks rented plots of land in return for giving a portion of their crop yield to the landowner, who were often their former master.

Sojourner Truth: (1797-1883) a former slave, she was an African American abolitionist and women’s rights advocate. She is best known for her speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?,” which she delivered at a women’s convention in 1851. During the Civil War she recruited black soldiers for the Union Army and collected supplies for the troops.

Southern Homestead Act: (1866) the act provided freed blacks preferential access to public lands in five southern states. However, the high cost and poor quality of the land defeated the purpose of the act.

Stonewall Jackson: (1824-1863) Lieutenant general of the Confederate States Army.

Thirteenth Amendment: (1865) abolished slavery in the Southern states.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 5 – Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

- Standard 3B – The student understands the Reconstruction programs to transform social relations in the South.

- 5-12 – Evaluate the goals and accomplishments of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

- 7-12 – Analyze how African Americans attempted to improve their economic position during Reconstruction and explain the factors involved in their quest for land ownership.

- Standard 3C – The student understands the successes and failures of Reconstruction in the South, North, and West.

- 7-12 – Assess how the political and economic position of African Americans in the northern and western states changed during Reconstruction.

- 7-12 – Analyze how the Civil War and Reconstruction changed men’s and women’s roles and status in the North, South, and West.

- Standard 3B – The student understands the Reconstruction programs to transform social relations in the South.