The civil rights era, in which marginalized groups demanded equal rights, dramatically altered American society. Galvanized by the times in which they lived, Latino artists became masters of socially engaged art, challenging prevailing notions of American identity and affirming the mixed indigenous, African, and European heritage of Latino communities. Many reinvigorated mural and graphic traditions in an effort to reach ordinary people where they lived and worked. Whether energizing genres like history painting, or creating activist posters or works that penetrate bicultural experiences, Latino artists shaped and chronicled a turning point in American history.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

Farm Workers' Altar

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. Colorado-based artist Emanuel Martínez created Farm Workers’ Altar to celebrate an important event in the Chicano movement. On March 10, 1968, in the fields near Delano, California, labor organizer César Chávez broke a twenty-five-day fast at a Mass celebrated at this altar. Which symbols do you see invoke this sense of unity between social and religious causes? Which symbols celebrate the diversity and character of humanity?

Observation: What do you see?

What does the size and shape of this artwork suggest about its purpose?

The upper surface of this piece is flat. The sides slope outward from the top to the base. This artwork is larger than you might think. It measures about the size of a table, 38 1/8 x 54 1/2 x 36 in. (96.9 x 138.5 x 91.4 cm.).

What motifs and symbols do you notice?

On the top panel of this artwork, a central cross is bordered by geometric designs in bright colors. The designs are reminiscent of those woven into Mexican blankets and tapestries. The top almost resembles a painted table cloth. Take a look at the longer sides of the altar. One side of the artwork depicts an image of Christ crucified. Look at the opposite side: what do you notice about the sun? What is the woman holding? What else do you notice about her, the landscape, and the border? Beneath a three-faced sun, an indigenous woman holds shafts of wheat in her right hand and a bunch of grapes in her left. The bright colors of her headband, the peace medallion on her necklace, and her pink dress stand out against a clear landscape of blue water and a green mountain. Ears of corn and grapevines decorate the borders of the image. Now look at one of the shorter sides. What do you notice about the positioning of the arms on this side? How about the skin tones and shirt sleeves? What are the hands grasping? Four arms of varied skin tones reach towards each other forming a box around a central symbol. The fists clench grapevines, working together to harvest the fruit.

On the top panel of this artwork, a central cross is bordered by geometric designs in bright colors. The designs are reminiscent of those woven into Mexican blankets and tapestries. The top almost resembles a painted table cloth. Take a look at the longer sides of the altar. One side of the artwork depicts an image of Christ crucified. Look at the opposite side: what do you notice about the sun? What is the woman holding? What else do you notice about her, the landscape, and the border? Beneath a three-faced sun, an indigenous woman holds shafts of wheat in her right hand and a bunch of grapes in her left. The bright colors of her headband, the peace medallion on her necklace, and her pink dress stand out against a clear landscape of blue water and a green mountain. Ears of corn and grapevines decorate the borders of the image. Now look at one of the shorter sides. What do you notice about the positioning of the arms on this side? How about the skin tones and shirt sleeves? What are the hands grasping? Four arms of varied skin tones reach towards each other forming a box around a central symbol. The fists clench grapevines, working together to harvest the fruit.

What is the central symbol?

This symbol, for the Farm Workers Union, is made up of an eagle’s head, in reference to the eagle that graces the Mexican flag, and an inverted pyramid that refers back to the pyramids of the ancient Aztecs. American farm workers in the 1960’s were largely migrants from Mexico and other parts of Central America. This emblem embodied their history and heritage.

This symbol, for the Farm Workers Union, is made up of an eagle’s head, in reference to the eagle that graces the Mexican flag, and an inverted pyramid that refers back to the pyramids of the ancient Aztecs. American farm workers in the 1960’s were largely migrants from Mexico and other parts of Central America. This emblem embodied their history and heritage.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

The work of art’s size, shape, and symbols provide us clues to its religious, social, and political significance. We know that this piece is large enough to be used as a table and that its surface is richly decorated with religious and political imagery. In Catholicism the altar is a symbol of Christ’s Last Supper, a place for physical and spiritual nourishment and a reaffirmation of faith. This altar commemorates the 1968 Catholic Mass held in Delano, California, where César Chávez broke the twenty-five-day fast he undertook to protest unfair employment practices and unsuitable work conditions for migrant laborers. Chávez, a religious and non-violent leader, co-founded the organization that later became the United Farm Workers. The Farm Workers Union commissioned Chicano artist Emanuel Martinez to create this altar even before it was known that it would be used at such a significant event. The arms surrounding the Union emblem symbolize the combined strength of all workers of every color skin. Martinez defined social struggle in Christian terms by combining elements of spirituality and mestizaje, the mixed racial heritage of Mexicans and their Chicano descendants.

The artist painted pre-Columbian and European symbols and figures on the altar to indicate the mestizo heritage that Chicanos celebrate. This altar is one of the most important icons of the early Chicano movement because of its visual images that represent cultural, social, and economic issues important to La Causa (the cause). On one side of the altar, a crucifix bears a brown-skinned Christ; on the other, an indigenous woman holds wheat stalks and grapes that prefigure the bread and wine of Holy Communion. These items also symbolize the fruitfulness of the earth. The woman represents the many workers who migrated from Mexico to California to harvest crops under deplorable conditions.

The motif of clasped hands from many races working together to gather the harvest surrounds an abstract black eagle on a red background, the symbol of the United Farm Workers of America, Chávez’s organization. Many workers who attended the Mass in the middle of a field, the site of their labor, would have recognized these symbols. The sun is formed from the mestizo image of a head with the central face composed of two profiles that represent both indigenous peoples and Europeans. These images, along with the peace symbol and the crucifix, evoke a sense of unity between social and religious causes and celebrate the diversity and character of humanity.

Camas para Sueños

Artist make choices in communicating ideas. What information can we learn about growing up in a Latino family from this painting? What clues does the artist give us about her hopes and dreams? What connections can be made amongst many American families? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

What are the figures on the roof doing?

What a beautiful night! Two girls lie back on the roof of their house to gaze up at a full moon. One points to the stars. What might they be thinking or saying to each other?

What is happening inside of the house?

What is happening inside of the house?

Through the window of this tidy, simple home, a mother adds a blanket to the bed, readying it for bedtime for her daughters. A religious cross flanked by palm leaves hangs on the wall beside the bed. A hairbrush and other accessories lay on a bedside table. From these details, we know that nurturing both home and family, as well as faith, are important to the occupants of this home.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

This scene is one of happy memories for the artist. Carmen Lomas Garza vividly recalls such an evening when she and her sister climbed onto their roof, looked up at a beautiful moon, and dreamed of their future. They had both wanted to be artists. From the age of 13, Lomas Garza read all the books she could about art and practiced drawing the world around her every day.

Lomas Garza grew up in a close-knit Mexican-American community in Kingsville, Texas. Though her family and neighbors were warm and loving, she often experienced prejudice outside of her community. She painted such scenes as these – positive images of family and friends enjoying everyday life – in celebration of her heritage and in hopes that others might likewise appreciate it. Lomas Garza has said, “Every time I paint, it serves a purpose–to bring about pride in our Mexican American culture.” Although this painting documents a specific Mexican American childhood experience, it honors families of all cultures that nurture their children’s dreams.

For centuries immigrants have come to America in hopes of finding a way to provide a safe, nurturing home for their families, and opportunities for their children to dream and realize their dreams. Is the artist’s aim of invoking shared aspirations for future generations realized by this work? What elements of the immigration experience has she omitted to create this scene?

Historical Background

Cesar Chavez and the Organized Labor Movement

The labor movement of earlier generations was reignited in part by the United Farm Workers (UFW), led by a labor union activist Cesar Chavez. He was committed to non-violent change and justice, inspired by Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi. Chavez worked to organize Mexican American farm workers in California, 1965, advocating for better wages, safer working conditions, and less exposure to pesticides.

An impediment to their cause was the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, a federal law which did not protect farm workers. This meant that is was up to the farm owners to recognize the UFW union as a bargaining agent. Chavez and his supporters implemented work stoppages and national boycotts against lettuce, table grapes, and wine to promote their message and gain support for the protection of farm workers.

Chavez was born to Mexican immigrants in 1927. His family moved from Arizona to California in search of migrant laborer jobs. After serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, Chavez returned home to California where he first experienced working with striking agricultural workers at the Community Service Organization. He went on to form the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) in 1962.

In 1965, the NFWA received national attention because of the Delano grape strike. The strike involved workers from the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) who walked off their jobs at grape farms, demanding that their wages be equal to the federal minimum wage. When the NFWA joined the strike, Chavez expressed the workers’ goals in a document called the Plan of Delano consisting of six main propositions.

- Chavez begins by defining the movement as a “social movement,” one in which the workers seek their “God-given rights as human beings.”

- The workers seek the support of the federal government and political groups. Chavez writes that legislators could have helped the workers, but instead chose to support farm owners. Chavez lists starvation wages, forced migration, sickness, illiteracy, and sub-human living conditions as just some of the effects of a system unfairly skewed against the workers.

- Chavez would like the support of the Catholic Church, reminding the church that the workers carry images of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico. He also quotes nineteenth century Pope Leo XIII, “Everyone’s first duty is to protect the workers from the greed of speculators who use human beings as instruments to provide themselves with money. It is neither just nor human to oppress men with excessive work to the point where their minds become enfeebled and their bodies worn out.”

- Chavez describes the suffering, poverty, and misery of agricultural workers, pointing out that the government protects the wealthy at the expense of the poor.

- Unity of all farm workers is crucial, no matter what their ethnic background may be. Chavez mentions the tactic some employers have used to divide the farm workers – offering them non-union contracts. Chavez stresses the need for union-negotiated contracts, as only through collective bargaining would real change happen.

- Finally, Chavez reiterates the workers’ intent to strike and not give up the fight. He terms the movement a revolution, referring to the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920 where poor people also sought basic human rights.

With the release of the Plan of Delano, Chavez quickly became a popular public speaker, inspiring under-represented and oppressed farm workers, both Latino and non-Latino alike. His next move was to lead protesters in an historic 340 mile-march from Delano, California to the state capital of Sacramento. The national attention received by the strikers ultimately pressured the farm into owners conceding to the strikers demands.

Senator Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez celebrate Catholic mass following the end of Chavez’s fast, 1968, Time Life Pictures, Getty Images.

Chavez also used hunger strikes and fasting as tools for protest. For three years, the UFW had been engaged with grape growers to sign contracts with the union. The strike gradually turned violent, with sheriffs and teamsters beating farm workers during strikes. Frustrated and impatient, many farm workers began to tire of Chavez’s insistence on non-violence. In an effort to diffuse the situation on both sides, Chavez engaged in a twenty five day hunger strike in 1968 to emphasize the importance of non-violence in order to achieve real, lasting change. Of his fast, Chavez wrote: “There was demoralization in the ranks, people becoming desperate, more and more talk about violence. People meant it, even when they talked to me. [The farm workers] would say, “Hey, we’ve got to burn those sons of bitches down. We’ve got to kill a few of them.”. . . I thought I had to bring the Movement to a halt, do something that would force them and me to deal with the whole question of violence and ourselves. We had to stop long enough to take account of what we were doing. So I stopped eating.” On the day that he broke his fast, Chavez was joined by thousands of supporters, including Senator Robert F. Kennedy, to celebrate Catholic mass and break bread. He would later write:

On the day I broke my fast, I was pretty much out of it, I was so weak. We had a mass at the county park. . . . At the park I was so much out of it, all I felt was a lot of people pushing and trying to get closer to the altar. It was hot. I remember arriving, a lot of people trying to say hello, trying to hug me while I was being held up because my legs were so weak. The mass was said by many priests, and many nuns came to distribute the bread. I couldn’t see the crowd because I was sitting down. . . . Because I was too weak, I couldn’t even speak my thanks, but Jim Drake [Chavez’s union aide] expressed my thoughts which I had put down earlier. “Our struggle is not easy. Those who oppose our cause are rich and powerful, and they have many allies in high places. We are poor. Our allies are few. But we have something the rich do not own. We have our own bodies and spirits and the justice if our cause as our weapons.

Indian political and spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi was one of his role models, Gandhi’s autobiography The Story of My Experiments With Truth opened Chavez’s mind to the possibilities of non-violent resistance, including hunger strikes. Of Gandhi, Chavez wrote, “The message for me is that of his non-violence and the fact that he was a doer. He made things happen . . . I lose faith in someone who doesn’t continue a project, who starts something and then leaves it. The world is full of us quitters. Even if Gandhi had not liberated India, he stayed with the project all his life. And that is my great attraction. He just didn’t give up.” After Chavez undertook his twenty-five day fast, he explained the need for his fast and the movement’s non-violent philosophies: “Knowing of Gandhi’s admonition that fasting is the last resort in the place of the sword, during a most critical time in our movement last February, I undertook a 25-day fast. I repeat to you the principle enunciated to the membership at the start of the fast: “If to build our union required the deliberate taking of life, either the life of a grower or his child or the life of a farm worker or his child then I would choose not to see the union built.” Gandhi’s peaceful ways provided Chavez with inspiration and motivation to work toward non-violent social change throughout his life.

Another important role model for Chavez was civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. King also advocated for non-violent social change, explaining why in his famous 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail”: “You may well ask, why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches, etc.? Isn’t negotiation a better path? You are exactly right in your call for negotiation. Indeed, this is the purpose of direct action. Non-violent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and establish such creative tension that a community that has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored.”

In fact, during his twenty five day fast in 1968, Chavez received a telegram from King that read: ““I am deeply moved by your courage in fasting as your personal sacrifice for justice through non-violence. Your past and present commitment is eloquent testimony to the constructive power of non-violent action and the destructive impotence of violent reprisal. Your stand is a living example of the Gandhian tradition with its great force for social progress and its healing spiritual powers.” The telegram was received just one month before King’s assassination.

Art for La Causa

The civil rights era of the 1960s, in which marginalized groups demanded equal rights, dramatically altered American society. Galvanized by the times in which they lived, Latino artists became masters of socially engaged art, challenging prevailing notions of American identity and affirming the mixed indigenous, African, and European heritage of Latino communities. Many artists reinvigorated mural and graphic traditions in an effort to reach ordinary people where they lived and worked. Whether energizing genres like history painting, or creating activist posters or works that penetrated bicultural experiences, Latino artists shaped and chronicled a turning point in American history.

The Latino Civil Rights movement began around the same time as the African American Civil Rights movement during the 1960s. The Latino community founds its voice in civil rights activist Cesar Chavez in their quest for equality. Chavez, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., implemented peaceful protest strategies in the effort to expand civil and labor rights for Latinos. The marches, strikes, and fasts that Chavez and others employed aided in raising awareness of unfair labor practices, such as low wages and poor working conditions facing the Latino community. These issues became compelling motivation for Latino artists to use their talents to raise awareness and engage others for La Causa. Their artwork, which began as an expression of public art forms, fueled ongoing political activism and a greater sense of cultural pride. Political banners and posters carried during marches and protests were some of the first art forms of the movement. While Emanuel Martinez’s Farm Workers Altar is an excellent example of early public art of the movement, Carmen Lomas Garza’s Camas para Sueños exudes cultural pride in depicting a scene of everyday life in a Mexican American family.

Farm Workers’ Altar

This altar was used during the celebration of Catholic Mass in 1968 when Cesar Chavez broke a twenty-eight day fast to protest the working conditions of migrant agricultural workers. This fast was the first Chavez undertook during his lifelong struggle against the injustices faced by the greater Latino community. His 1968 fast was in response to a disagreement over Chavez’s non-violent protest tactics among his fellow union activists. The disgruntled farm workers believed that Chavez’s insistence on peaceful marches and strikes were not an effective way to attain recognition as a union by the crop growers. The workers’ non-union unregulated status meant that the crop growers were able to take advantage of them with low wages, long working hours, and unsafe working conditions. Yet, Chavez’s perseverance and dedication to the cause inspired many and swayed them to his way of thinking. When Chavez broke his fast on March 10, 1968, he was joined by ten thousand supporters, including Senator Robert F. Kennedy and United Farm Workers’ co-founder Dolores Huerta.

Artist/ activist Emanuel Martinez was inspired by Chavez’s passionate speeches and his own Mexican-American heritage to create the imagery on the altar. Martinez incorporated many of the Mexican, Christian, and pre-Columbian symbols that were used throughout el Movimiento movement on banners, posters, and flyers. He was just twenty-one years old when commissioned by the Episcopal Bishop of Los Angeles for the project. One side of the altar depicts a brown-skinned Jesus Christ; on the opposite side, an indigenous woman wears a peace symbol, her hands grasping grapes and wheat. The dual-faced sun above her denotes the mixed heritage of Mexican Americans; the union of Spanish and indigenous peoples. The side panels display a cross made from corncobs and a circle of linked arms with multiple skin tones, representing strength and unity. The symbol of the United Farm Workers, a black eagle inside a red circle, is placed inside the circle. For more information on the imagery in Farm Workers’ Altar, please see Activity: Observation and Interpretation.

Martinez had spent years working for the Latino civil rights cause, joining the country’s first Chicano civil rights organization Crusade for Justice, in Denver, Colorado. Unlike Lomas Garza, whose work is devoted to small, intimate pieces, the bulk of Martinez’s artwork is on a large scale, mostly mural paintings for community organizations. In these murals, Martinez incorporates the same symbols of mestizo heritage as he did in the Farm Workers’ Altar – images of pre-Columbian civilizations of Mexico and of past and present historical figures who have contributed to the Mexican and Mexican American struggle for justice. He describes the purpose of his activist artwork as, “aimed at strengthening the unity of our community by encouraging pride and bringing cultural nationalism to the forefront of the Chicano civil rights movement. I became committed to this goal and did everything I could to help achieve it.”

Camas para Sueños

Like Emanuel Martinez, Chicana artist Carmen Lomas Garza was inspired by the Latino rights movement, responding to social change and discrimination through her artwork. Lomas Garza’s paintings address her experiences growing up in the 1950s in an extended Mexican American family on the Texas/ Mexico border. She writes:

Most of my images are recollections of my childhood in South Texas. Relatives and friends are depicted as remembered in everyday activities or in unusual events such as a session with a faith healer or a fight. . . . Every time I paint, it serves a purpose–to bring about pride in our Mexican American culture. When I was growing up, a lot of us were punished for speaking Spanish. We were punished for being who we were, and we were made to feel ashamed of our culture. That was very wrong. My art is a way of healing these wounds.

Within the close-knit Mexican American community of Kingsville, Texas, Lomas Garza received love and encouragement from her family and from a broad range of friends and neighbors. But when she ventured outside the comfort of her community, she experienced prejudice. The Chicano movement helped give her new pride in her mixed Native American and Spanish ancestry. She writes: “When I was in high school, the [United Farm Workers] came marching through town. That was really a crucial turning point for the Chicano movement because it brought to life in a very obvious way the inequities. And so I became involved with the Chicano movement as an artist. My answer to answering what I could do within the Chicano movement was to do my artwork.” In college she decided to dedicate her art to the Mexican American community to show her gratitude and celebrate her rich mestizo heritage. Lomas Garza hoped that by painting positive imagery of Mexican American community life, her art might help eliminate the racism she experienced as a child.

Her works focus on subjects such as the importance of childhood memories and family traditions. Lomas Garza’s work is personal and intimate – even the scale of her work is small – inviting the viewer to look closely and engage with community traditions and family interactions depicted in her work. Her 1985 painting Camas para Suenos [translation: Bed for Dreams] focuses on the dynamics of Mexican American family life. The lower half of the artwork shows a mother providing comfort for her children in the form of a freshly made bed, religious imagery, and a well-stocked chest of drawers. On the roof above her, her daughters lay by the light of the moon, pointing to the stars and dreaming of their future. The artist suggests that the girls’ dreams are within reach, especially when their home life has provided them a good foundation.

Primary Source Connections

Robert F. Kennedy Statement on Cesar Chavez, March 10, 1968

This is the original copy of Senator Kennedy’s 1968 remarks given at the United Farm Workers’ Union rally in Delano, California when Cesar Chavez broke his 25 day fast advocating for non-violent social change.

Telegram from Martin Luther King Jr. to Cesar Chavez, March 5, 1968

Telegram from Martin Luther King Jr. to Cesar Chavez, March 5, 1968

King’s original Western Union telegram to Chavez during the latter’s fast, praising him for his adherence to non-violent social change and for his inspiring example to Latinos and African Americans alike.

Read it at United Farm Workers.org

Oral History Interview with artist Carmen Lomas Garza, 1997 Apr 10- May 27, Archives of American Art

Lomas Garza discusses her education at Texas A&I University (now Texas A&M) and graduating from the University of Texas at Austin with a B.S. in art education (1969); her activism in the Chicano movement during her college years; joining the farm workers march in Kingsville in 1965; and preserving her Mexican-American traditions as a basis for her identity.

Bracero History Archive – The Bracero History Archive collects and makes available the oral histories and artifacts pertaining to the Bracero program, a guest worker initiative that spanned the years 1942-1964. Millions of Mexican agricultural workers crossed the border under the program to work in more than half of the states in America.

Literary Connections

Books:

Family Pictures/ Cuadros de Familia, 2005, Carmen Lomas Garza

Family Pictures/ Cuadros de Familia, 2005, Carmen Lomas Garza

Artist and author Lomas Garza shares her memories of growing up Mexican-American in Kingsville, Texas. The juxtaposition of artworks and personal stories (in both Spanish and English) help students understand and experience day-to-day life in a Mexican-American family and community. The book includes an introduction by author Sandra Cisneros.

The House on Mango Street, 1984, Sandra Cisneros

The House on Mango Street, 1984, Sandra Cisneros

This is the coming-of-age story of a young Chicana (Mexican-American) girl, Esperanza Cordero, growing up in Chicago. As a young girl, Esperanza’s family moves to the house on Mango Street from a dilapidated apartment, yet the small house is not the improvement she had hoped it was, as it is still in a low-income, racially segregated part of Chicago. The story is told through a series of vignettes as Esperanza matures into a woman, with the dream of one day leaving the barrio (the Mexican-American neighborhood in which she lives).

Bless Me, Ultima, 1972, Rudolfo Anaya

Bless Me, Ultima, 1972, Rudolfo Anaya

One of the first widely read Chicano novels, the books explores a young Mexican American boy’s coming-of-age search for personal and ethnic identity in the context of the social changes he experiences as a Chicano living in New Mexico in the 1940s.

Poetry:

“I am Joaquin,” 1968, Rudolfo “Corky” Gonzalez

Written at the height of the Chicano Rights movement, this epic poem discusses the plight of the Chicano people in their quest to achieve equal rights and economic/ social justice. It also addresses the struggle of Mexican-Americans to assimilate into American culture, while trying to hold on to their Mexican culture. In 1969 the poem was adapted into a 20 minute film as part of El Teatro Campesino.

Artwork Connections

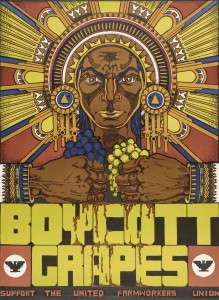

Boycott Grapes, Support the United Farm Workers Union, 1973, Xavier Viramontes

Boycott Grapes, Support the United Farm Workers Union, 1973, Xavier Viramontes

The fierce attitude of Viramontes’s Aztec warrior speaks to the heightened intensity of the pro-labor struggle when Cesar Chavez initiated a new grape boycott in 1973. Viramontes, a Vietnam veteran, chose a martial subject to support Chicano rights. The warrior’s visceral spilling of sacrificial blood and the decorative splendor of his garments symbolically affirm the ethnic heritage shared by many field-workers.

Tamalada, 1990, Carmen Lomas Garza

Tamalada, 1990, Carmen Lomas Garza

Lomas Garza’s folk-styled works document the lives of Mexican Americans and often portray memories of her own family in South Texas. The artist writes: “This is a scene from my parent’s kitchen. Everybody is making tamales. My grandfather is wearing blue overalls and a blue shirt. I’m right next to him with my sister Margie.We’re helping to soak the dried leaves from the corn. My mother is spreading the cornmeal dough on the leaves and my aunt and uncle are spreading the meat on the dough. My grandmother is lining up the rolled and folded tamales ready for cooking. In some families just the women make tamales, but in our family everybody helps.”

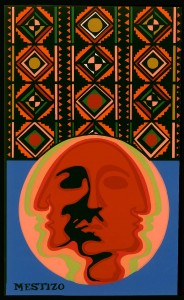

Mestizo, 1974, Amado Peña, Jr.

Peña’s Mestizo became an iconic image in the construction of Chicano identity that began to take place in the late 1960s. Many Chicanos were drawn to the ideas of Mexican intellectual Jose Vasconcelos, especially his definition of mestizaje presented in his book La raza cosmica (1925). For Vasconcelos, racial mixing between the “four races” – defined as indigenous, European, Asian, and African – would create a superior race “more capable of fraternity and universal vision.” This spiritual and positive view of a racialized identity appealed to Chicanos, who sought to affirm their mixed, indigenous heritage in the face of American racism and cultural assimilation. – Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art

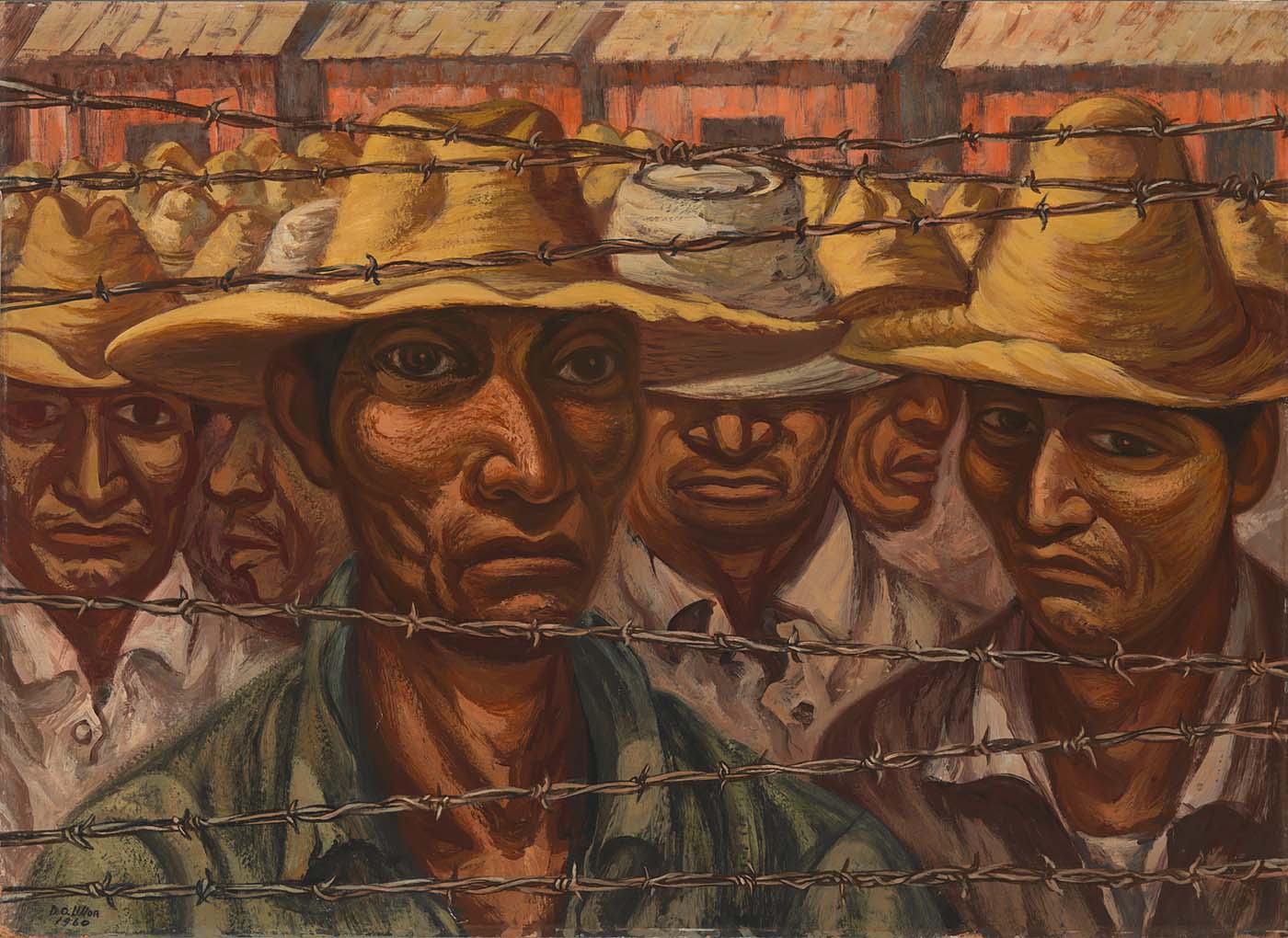

Braceros, 1960, Domingo Ulloa

Born in Pomona, California, the son of migrant workers, Domingo Ulloa’s artwork is influenced by the 1930s-era, politically charged artwork of the Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. Ulloa’s artwork focuses on the social ills of society such as racism, social inequality, and police brutality. Braceros draws upon the artist’s visits to bracero (manual labor) camps in San Diego County, California. The Bracero Program (1942-1964) was a series of laws and bi-lateral agreements between the United States and Mexico, in which millions of Mexican nationals came to the U.S. to work on short-term agricultural labor contracts.

Media

“Camas para Sueños” by Carmen Lomas Garza (3 min)

This audio podcast series discusses artworks and themes in the exhibition “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In this episode, director Eizabeth Broun discusses “Camas para Sueños by Carmen Lomas Garza.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Subject: Art

Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art – Smithsonian American Art Museum

This exhibition presents more than ninety works of art across all media by significant Latino artists active since the mid-twentieth century and gives voice to their broader American experience. (bilingual website)

Subject: History

How Cesar Chavez Changed the World – Smithsonian Magazine

The article explores how the farm worker’s initiative improved lives in America’s fields, and beyond.

Subject: Music

Rolas de Aztlan: Songs of the Chicano Movement – Smithsonian Folkways

Songs of struggle, hope, and vision fueled the Chicano Movement’s quest for civil rights, economic justice, and cultural respect. Rolas de Aztlán (songs from the Chicano ancestral homeland) spotlights 19 milestone recordings made between 1966 and 1999 by key Chicano artist/activists—Daniel Valdez, Los Lobos del Este de Los Angeles (later Los Lobos), Agustín Lira and Teatro Campesino, Los Alacranes Mojados, Conjunto Aztlan, and many more.

Música Latina: Sounds of Latino USA – Smithsonian Folkways

Latino music speaks to the heart of personal and social identity, issues of survival for immigrant communities who are adjusting to alien social environments and building a new spirit of unity. Music embodies knowledge, meaning, and spirit, essential assets to envisioning and living a life in which Latinos can feel genuinely themselves. Musicians and communities continually construct new meanings for their music, which serves both social and aesthetic needs.

Tradiciones/ Traditions: The Expanding Universe of Música Latina – Smithsonian Folkways

Over forty-five million people of Hispanic descent make the United States their home. Front-page news proclaims Hispanics the largest minority group and the fastest-growing segment of the population, having more than doubled since 1989 and accounting for half the total population growth in the United States since 2001. Concurrently, the twenty-first century has seen an explosion of Latino music, usually called música latina in the windows and bins of record stores and on the banners of digital music retailers.

Lesson Plans

Latino Family Stories – Smithsonian Education

Students examine the work of American painter Carmen Lomas Garza in this set of four lessons, divided into grades K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12. The youngest students write a story based on a scene from Garza’s childhood. Older students consider the role that culture plays in our lives

Glossary

Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee: (AWOC) a primarily Filipino workers’ rights organization, AWOC merged with the NFWA in 1966 to form the United Farm Workers.

La Causa: Spanish for “The Cause.” A term associated with the Chicano civil rights movement.

Cesar Chavez: (1927-1993) union leader and labor organizer. Founder of the NFWA (later the UFW), Chavez advocated for farm workers’ rights and employed Gandhi’s tradition of peaceful, non-violent social change.

Chicano: a chosen identity of an American of Mexican origin or descent. The term came to prominence during the Chicano movement. Some members of the community view the term with negative connotations, as it was used previously in a derogatory manner.

Chicano movement: a period of widespread social and political activism within the Mexican American community during the 1960s and 1970s; also known as the Chicano Civil Rights Movement.

Community Service Organization: a California-based Latino civil rights organization. Most well-known for providing Cesar Chavez his first foray into civil rights.

Crusade for Justice: a Denver, Colorado arm of the Chicano movement, founded in 1967 by political activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez.

Dolores Huerta: (1930 – ) labor leader and civil rights activist, she co-founded what would become the United Farm Workers (UFW) with Cesar Chavez. She continues to be an advocate for workers’, immigrants’, and women’s rights.

Letter from Birmingham Jail: (1963) authored by Martin Luther King Jr., the letter was written during King’s stint in a Birmingham, Alabama jail. It defends the civil rights movement’s use of non-violent resistance to racism.

Mahatma Gandhi: (1869-1948) Indian political and spiritual leader during India’s struggle for independence from Great Britain. Known for his peaceful, passive, non-violent forms of protest.

Martin Luther King Jr.: (1929-1968) African American civil rights leader and Baptist minister, who rose to prominence fighting the segregation of public transportation. He was an active supporter of Gandhi’s method of peaceful, non-violent social change.

mestizo: Spanish term used to describe a person of mixed European and Amerindian (pre-Columbian) descent.

Mexican Revolution: (1910-1920) an armed struggle that began in 1910, ended dictatorship in Mexico and established a constitutional republic. Groups led by revolutionaries Francisco Madero, Pascual Orozco, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, participated in the long and costly conflict.

el Movimiento: Spanish term meaning “The Movement,” used in reference to the Chicano rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

National Farm Workers Association: (NFWA) led by Cesar Chavez, the NFWA merged with its primarily Filipino counterpart, AWOC, to form the United Farm Workers.

National Labor Relations Act of 1935: (also known as the Wagner Act) a U.S. labor law which established legal rights for most workers, excluding farm workers and domestic workers.

Plan of Delano: The title alludes to the early twentieth century Mexican revolutionary hero Emiliano Zapata. His statement of goals was called “Plan de Ayala.”

pre-Columbian: this term refers to era comprised of many subdivisions which denotes the vast span of time in the Americas before the arrival and influence of European cultures. The term’s name is derived from Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, so it means quite literally “the time before Columbus,” or before Columbus’ arrival in 1492.

la raza: Spanish term which translates to “the race.” Used by Latinos/ Hispanics to express ethnic pride.

Robert F. Kennedy: (1925-1968) United States Senator, advocate for civil rights. Kennedy joined Chavez at the end of his 1968 fast in support of the movement.

United Farm Workers: (UFW) a labor union of farm workers in the United States. As a result of the commonality of goals between the AWOC and the NFWA, and after a series of strikes in 1965, the groups united to form the UFW in 1966.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 9 – Post War United States (1945-early 1970s)

- Standard 4A – The student understands the “Second Reconstruction” and its advancement of civil rights.

- 5-12 – Evaluate the agendas, strategies, and effectiveness of various African Americans, Asian Americans, Latino Americans, and Native Americans, as well as the disabled, in the quest for civil rights and equal opportunities.

- 9-12 – Assess the reasons for and effectiveness of the escalation from civil disobedience to more radical protest in the civil rights movement.

U.S. History Content Standards Era 10 – Contemporary United States (1968-the present)

- Standard 2B – The student understands the new immigration and demographic shifts.

- 5-12 – Analyze the new immigration policies after 1965 and the push-pull factors that prompted a new wave of immigrants.

- 9-12 – Identify the major issues that affected immigrants and explain the conflicts these issues engendered.