The postwar era of American life brought about a period of tremendous social and cultural change. This era highlighted the economic disparity between the rising middle class and those in poverty. A postwar economic boom led to an increase in productivity and a higher GDP. Consequently, the middle class took advantage of technological advances such as new means of transportation and lower home prices, and migrated out of the cities. This propelled American suburbanization and the expansion of the crabgrass frontier. The people that were left behind in the urban areas after the middle-class migration were those who could not afford to move: the poor and the vast majority of minorities and immigrants. The depiction of a questionably viable Brooklyn neighborhood in Harvey Dinnerstein’s painting Brownstone depicts the situation of those left behind. In comparison, we have Roger Brown’s painting Natural Bridge, depicting the “new frontier.” The painting presents a cookie-cutter view of suburbia. The artwork is tinged with unnatural colors and a lack of diverse figures, provoking feelings of inaccessibility, sterility, and perhaps a loss of vibrancy.

Activity: Observe and Interpret

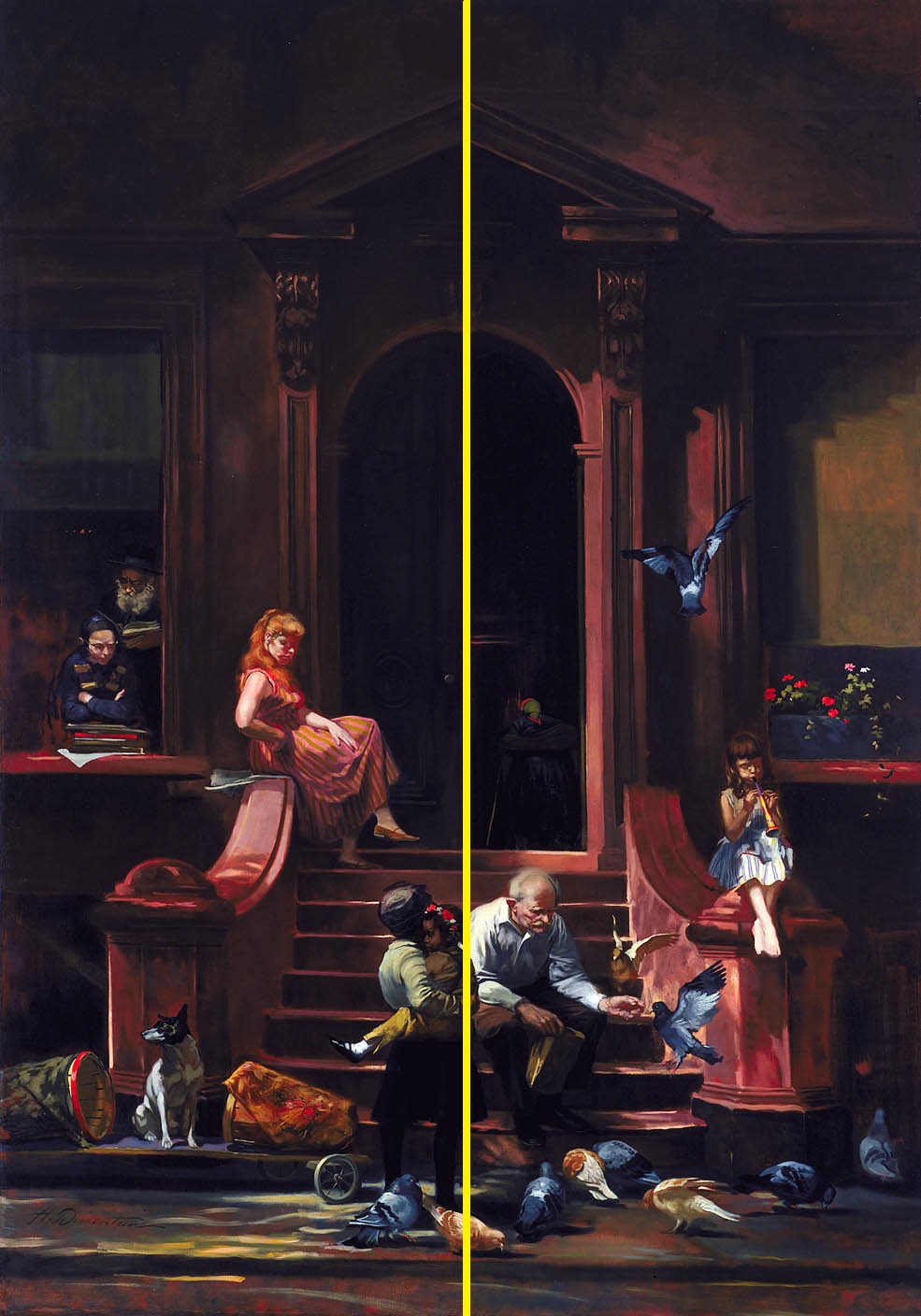

Brownstone

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What can we learn about urban life in the post-war United States from this painting? What message is Harvey Dinnerstein trying to convey? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

Take a closer look at each individual depicted in this scene. Then, considering them as a group, what do you notice about the people represented?

A diverse group of people congregates on the front steps of an urban brownstone. The people are old and young, male and female, representing different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. The clothing and hairstyles of the two male figures in the window indicate that they are probably part of a Hasidic Jewish community. There is a red-haired young woman, perhaps Irish, sitting at the top of the steps. Two young African American girls stand on the sidewalk. One of them is looking at an old man sitting on the steps, feeding a flock of pigeons. A little girl, ankles crossed and barefoot, is perched atop the end of the bannister playing a horn.

Dinnerstein sketched people he saw on the streets outside his studio and elsewhere around the city and used them as figures in his painting. He depicted his daughter Rachel as the girl playing the horn, and also included his neighbor’s dog, sitting on a strange wagon pieced together from odds and ends and covered in a colorful tapestry.

What clues has the artist given us about the setting of this painting?

The style of architecture represented in this painting – brownstone townhouses – are most commonly found in urban areas, especially on the East Coast. We don’t see any grass or gardens, but there is a box of flowers on the window ledge, and the shadows on the sidewalk suggest that there might be trees on the street. We see a flock of pigeons, birds commonly found in cities. The group of people Dinnerstein has represented indicates that we are looking at a diverse, urban neighborhood. Imagine the sounds you might hear if you stepped into this scene – the little girl’s horn, the beating of the pigeons’ wings, perhaps the wagon rolling or the dog barking – the neighborhood is full of life. Dinnerstein painted this scene based on a combination of several buildings in his neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York.

The style of architecture represented in this painting – brownstone townhouses – are most commonly found in urban areas, especially on the East Coast. We don’t see any grass or gardens, but there is a box of flowers on the window ledge, and the shadows on the sidewalk suggest that there might be trees on the street. We see a flock of pigeons, birds commonly found in cities. The group of people Dinnerstein has represented indicates that we are looking at a diverse, urban neighborhood. Imagine the sounds you might hear if you stepped into this scene – the little girl’s horn, the beating of the pigeons’ wings, perhaps the wagon rolling or the dog barking – the neighborhood is full of life. Dinnerstein painted this scene based on a combination of several buildings in his neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York.

Divide the painting down the middle, into two halves. What do you notice?

Dinnerstein chose to compose the painting so that the doorway of the brownstone is centered precisely on the mid-point of the canvas. This architectural symmetry, in addition to the repeated use of vertical and horizontal lines, gives the scene balance and stability.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

Harvey Dinnerstein combined his sketches and memories of people and places in Brooklyn into this scene of urban community life in the late 1950s. In Brownstone, he intentionally chose to represent a diverse array of people, and included signs of vibrancy and life, including the blooming flowers, the music from the little girl’s horn, and the colorful wagon. Although there are shadows and darkness, The composition of the painting, employing repetition of vertical and horizontal lines and architectural symmetry, gives the scene a sense of calm, balance and tranquility.

At the time Dinnerstein created this painting, many middle class Americans were migrating out of cities in favor of the suburbs, taking advantage of new means of transportation and more affordable homes stemming from a post-war economic boom. Those who stayed in the city were often minorities or immigrants. Dinnerstein, who grew up, lived, and worked in Brooklyn, wanted to paint a tribute to the urban neighborhood community as a still-vital societal institution. By making the ordinary people of Brooklyn the subjects of his painting, Dinnerstein was celebrating the multicultural and inter-generational communities that he felt made urban life so vibrant, yet commenting on the lack of wage-earning middle-class Americans who were financially able to move to the suburbs.

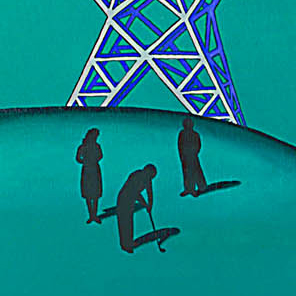

Natural Bridge

Artists make choices in communicating ideas. What kind of impression of suburban America is Roger Brown trying to convey in this painting? What visual clues has he given us? Observing details and analyzing components of the painting, then putting them in historical context, enables the viewer to interpret the overall message of the work of art.

Observation: What do you see?

What natural elements are included in this landscape? What artificial elements?

The feature that gives this painting its title, the natural bridge, is ironically one of the few natural elements included in this scene. Three transmission towers connected by power lines loom large over the landscape, and wide, smoothly paved roads and walkways cut through the scenery. Two nearly identical homes side by side, lined with manicured bushes give the painting a suburban feel. The bushes, which are repeated throughout the composition, seem to glow with a neon light. The grass is unnaturally smooth and texture-less, its color almost chemical. The composition itself is somewhat unnatural, with a surreal, flattened perspective.

The feature that gives this painting its title, the natural bridge, is ironically one of the few natural elements included in this scene. Three transmission towers connected by power lines loom large over the landscape, and wide, smoothly paved roads and walkways cut through the scenery. Two nearly identical homes side by side, lined with manicured bushes give the painting a suburban feel. The bushes, which are repeated throughout the composition, seem to glow with a neon light. The grass is unnaturally smooth and texture-less, its color almost chemical. The composition itself is somewhat unnatural, with a surreal, flattened perspective.

Where do you see contrasts between light and dark, or illumination and shadow in this painting?

The colors of the sky suggest that this scene takes place at dusk, with the sun setting and day transitioning into night. Two of the three transmission towers appear dark, as silhouettes on the horizon, while the one closest to us appears light. One of the four windows we see is illuminated with yellow light, while the other three appear dark. The dark bushes are artificially illuminated with a neon glow. Shadows are ubiquitous throughout the painting, from the human figures to the palm trees to the natural bridge.

The colors of the sky suggest that this scene takes place at dusk, with the sun setting and day transitioning into night. Two of the three transmission towers appear dark, as silhouettes on the horizon, while the one closest to us appears light. One of the four windows we see is illuminated with yellow light, while the other three appear dark. The dark bushes are artificially illuminated with a neon glow. Shadows are ubiquitous throughout the painting, from the human figures to the palm trees to the natural bridge.

How would you describe the human figures in this painting?

We see a number of figures in this painting, men and women in silhouette with no real distinguishing features. They are playing golf, strolling leisurely, and taking in the sight of the natural bridge, and yet they seem posed, like they could have been cut and pasted out of a tourism brochure or real estate ad. The womens’ silhouettes recall the fashion of the 1940s. All the people are seemingly dwarfed by the landscape elements. A lone figure appears in a dark window of one of the houses.

We see a number of figures in this painting, men and women in silhouette with no real distinguishing features. They are playing golf, strolling leisurely, and taking in the sight of the natural bridge, and yet they seem posed, like they could have been cut and pasted out of a tourism brochure or real estate ad. The womens’ silhouettes recall the fashion of the 1940s. All the people are seemingly dwarfed by the landscape elements. A lone figure appears in a dark window of one of the houses.

Interpretation: What does it mean?

A handful of nondescript, silhouetted figures occupy this manicured landscape, overshadowed by man-made, artificial structures. The people appear posed, almost as props in an advertisement. In Natural Bridge, Roger Brown captures a boredom and generic-ness he saw as characteristic of mid-century suburban life in America. The flattened perspective, chemical colors, contrasting shadows and illumination, and eerie emptiness of the streets contribute to a sense of anxiety lying just below the pristine surface.

Literary Connections

On the Road, 1957, Jack Kerouac

On the Road, 1957, Jack Kerouac

The House on Mango Street, 1984, Sandra Cisneros

This is the coming-of-age story of a young Chicana (Mexican-American) girl, Esperanza Cordero, growing up in Chicago. As a young girl, Esperanza’s family moves to the house on Mango Street from a dilapidated apartment, yet the small house is not the improvement she had hoped it was, as it is still in a low-income, racially segregated part of Chicago. The story is told through a series of vignettes as Esperanza matures into a woman, with the dream of one day leaving the barrio (the Mexican-American neighborhood in which she lives).

The Rose That Grew from Concrete, 1999, Tupac Shakur

A series of poems written by the late rapper in his teenage years, the poems cover subjects ranging from inner-city poverty, the African American experience in America, and his dreams and aspirations.

Artwork Connections

U.S. Highway 1, 1962, Allan D’Arcangelo

In 1962, D’Arcangelo embarked on a series of pictures depicting US Highway 1 on the East Coast. This painting was the first in the series, and served as inspiration for five similar works created between 1962 and 1963. Dark green silhouettes of trees flank the two-lane highway. The sky above is a solid plane of dark blue. The space is both flat and penetrating. Signs along the highway appear to float over the road as if time has been suspended. This surreal, almost dreamlike quality indicates a major difference between D’Arcangelo’s conception of the highway and road imagery presented to the American public by writers such as Jack Kerouac and photographers like Robert Frank. The latter see the road as a place where things happen, where rites of passage occur and stories unfold. For D’Arcangelo, the road is a place without time and without characters—just the hypnotic repetition of road signs and billboards and the forward motion of the car.

Cape Cod Morning, 1950, Edward Hopper

Cape Cod Morning, 1950, Edward Hopper

In Cape Cod Morning, a woman looks out a bay window, riveted by something beyond the pictorial space. She is framed by tall, dark shutters and the shaded façade of the oriel window. The brilliant sunlight on the side of the house contrasts with the blue sky, trees, and golden grass that fill the right half of the canvas. The painting tells no story; instead, the woman’s tense pose creates a sense of anxious anticipation, and the bifurcated image implies a dichotomy between her interior space and the world beyond.

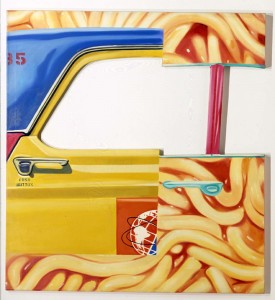

The Friction Disappears, 1965, James Rosenquist

The Friction Disappears represents the effortless flow of pictures and information in our culture, where unrelated or contradictory ideas overlap one another. Rosenquist painted the car in the same hot hue as the canned spaghetti simply because he liked the color. The tiny electrons orbiting the globe on the car door are like the paths of ideas and images crisscrossing in the modern world. Rosenquist compares the uncanny combinations that result to “two soap bubbles colliding and coming together instead of destroying each other.”

The Waiting Room, 1959, George Tooker

George Tooker grew frustrated with the bureaucracy while trying to obtain building permits for a house he bought in New York. He painted several images that show “faceless” government workers and run-down people getting nowhere (Garver, George Tooker, 1985). The clinical interior of The Waiting Roomevokes the conformity of the 1950s and emphasizes the pale, drawn expressions on the figures. The people stand in numbered boxes, evoking ideas of standardization that force people into predefined categories. The man on the left appears to be in charge of the “sorting,” creating a sinister view of government scrutiny.

The Stranger, ca. 1957-58, Hughie Lee-Smith

The Stranger, ca. 1957-58, Hughie Lee-Smith

Like many other artists of the Cold War era, Hughie Lee-Smith explored themes of exclusion and alienation in his paintings. He believed that the African American experience in particular was one of rejection and isolation and his feelings of racial disparity frequently influenced his work. In The Stranger, a lone figure stands in the foreground engulfed by a brown and green hillside. The man is frozen mid-gesture, looking over his shoulder at a wide gulf separating him from the cluster of homes behind him. The man’s race is ambiguous and features blurred, a choice Lee-Smith made in order to symbolize “everyman.”

Media

Meet the Artist: Harvey Dinnerstein (4 min)

Harvey Dinnerstein grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in Brownsville, Brooklyn. He studied art in New York and Philadelphia, and was an instructor at the Art Students League for many years. Dinnerstein started his career just as abstract expressionism was beginning to take hold in America. He rejected this new style, however, and focused on emphasizing the “traditions of the past” in his realistic, detailed images. Dinnerstein paints from life, and many of his images show intimate, poignant views of the people and buildings of New York and Brooklyn, where he has lived for most of his life.

Additional Smithsonian Resources

Exploring all 19 Smithsonian museums is a great way to enhance your curriculum, no matter what your discipline may be. In this section, you’ll find resources that we have put together from a variety of Smithsonian museums to enhance your students’ learning experience, broaden their skill set, and not only meet education standards, but exceed them.

Glossary

Beat Generation: A group of American writers and artists popular in the 1950s and early 1960s, influenced by Eastern philosophy and religion and known especially for their use of nontraditional forms and their rejection of conventional social values.

GDP: (Gross Domestic Product) the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period.

Standards

U.S. History Content Standards Era 9 – Post War United States (1945-early 1970s)

- Standard 1A – The student understands the extent and impact of economic changes in the postwar period.

- 5-12 – Explain the reasons for the sustained growth of the postwar consumer economy.

- 7-12 – Explain the growth of the service, white collar, and professional sectors of the economy that led to the enlargement of the middle class.

- 9-12 – Analyze the continued gap between poverty and the rising affluence of the middle class.

- Standard 1B – The student understands how the social changes of the postwar period affected various Americans.

- 9-12 – Explain the expansion of suburbanization and analyze how the “crabgrass frontier” affected American society.

- Standard 3B – The student understands the “New Frontier” and the “Great Society.”

- 5-12 – Evaluate the domestic policies of Kennedy’s “New Frontier.”

- 7-12 – Assess the effectiveness of the “Great Society” programs.